Elephant dung perfumes the air, a fresh, sweet smell, with undertones of sour vegetation. These balls of waste, scattered across the Kenyan savanna, carry the aroma of the bush, an open sea of acacia trees, aloe vera, Sansevieria, and drapes of elephant pudding, a succulent vine that tastes like salty snap beans but smells like bread dough.

Without elephants, much of Kenya—the swaths of savanna in the central and southern parts of the country—would look and smell different than it does today. It would not support the Samburu warriors herding cattle or the fleet packs of ungulates bounding past them. Without large herbivores, the wilderness would look much more like sparsely inhabited parts of the Americas, Europe, and Siberia—forests dominated by large trees, with mainly small animals darting about in the shadows. This may seem like a healthy ecosystem, but some researchers say it is far from natural—or ideal. Giant herbivores have shaped Earth’s ecosystems for millennia. Today, only Africa retains a hint of epochs past, when large animals, or “megafauna,” dictated the shape of the landscape on every habitable continent. A world without large herbivores—much of the world today—means a loss of grassland, scrub forest, biodiversity. Hello trees, goodbye wilderness.

Matthew Mihlbachler, a paleontologist, sits at a table on the 8th floor of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. We’re surrounded by fossilized Jumbos, giants in varying shades of white and ivory, animal remains from the order Proboscidea that evolved about 55 million years ago and includes elephants, mammoths, and mastodons.

“Proboscidea moved through the landscape knocking down trees and pushing them over,” Mihlbachler says. “They are deforesters basically.” The scientist teaches anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology, College of Osteopathic Medicine. His research focus, however, is paleoecology and large herbivores.

We talk and then walk between rows of metal cupboards, opening them and sliding out drawers full of bones, running fingers over ridged molars, some roughly football-sized, and a couple pounds heavier. Large herbivores like elephants can eat practically an entire landscape, the only limiting factor (aside from human hunters) being the swiftness of plant regeneration.

“It’s profound. When you go to Africa, to an ecosystem that contains elephants and lots of other large animals—you know, the entire world used to be like that,” says Mihlbachler.

Only 15,000 to 20,000 years ago, North America supported at least three Proboscidea species. That grassy, shrubby world was the natural order reaching back to about 24 million years ago, when Proboscidea really hit their stride, leaving their African homeland to lumber forth, conquer, and redesign much of the world. Around that time, the Miocene epoch, the climate changed. The world cooled. Grasses, once rare, spread, and various large herbivores evolved elongated “high-crowned” molars to compensate for getting word down by chomping grasses, tree bark, and poky plant bits. Grass, in particular, ravages teeth—it’s gritty and grainy, characteristics that likely evolved as a defense against herbivores. This evolutionary feedback probably helped both grassy habitats and Proboscidea spread.

Miocene fossil sites reveal a world awash in giant to less-giant-but-still-big plant-eaters with the ability to eat tough plants: multiple species of Proboscidea, rhinos, horses, camels, and tapirs. By this point, mammal forms were essentially modern. By the end of the Miocene, roughly 1.8 million years ago, huge ecosystems around the planet were created and maintained by megafauna, particularly Proboscidea.

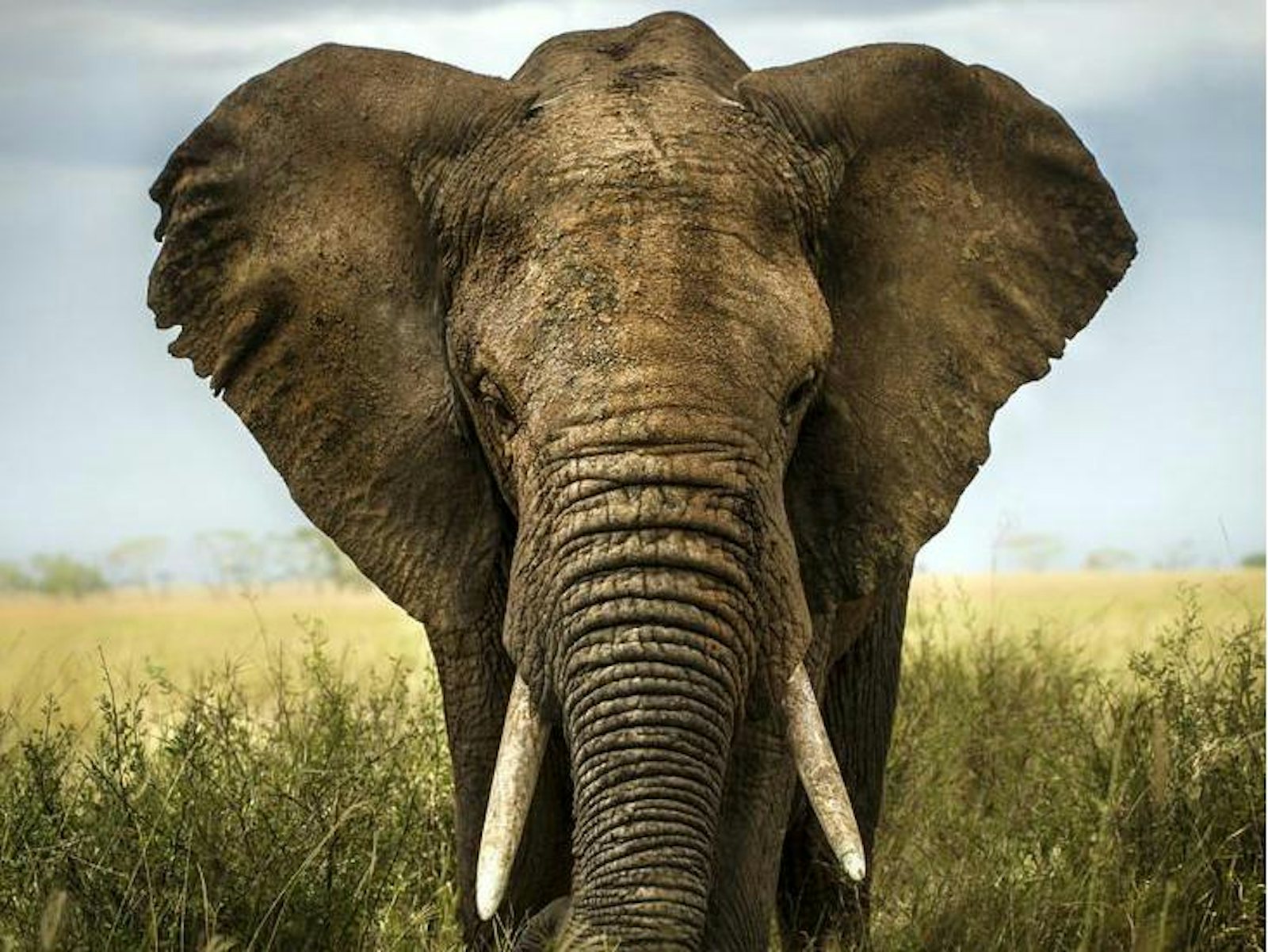

If the modern humans who emerged in East Africa about 200,000 years ago leapt into the present but stayed rooted in place, they would recognize the current, elephant-influenced landscape. (Let’s assume, for a moment, an absence of roads, cars, and other trappings of 21st-century living.) They would spot familiar animal tracks. They would know well the fibrous balls of poop, almost as big as a bowling ball, strewn across the ground, living treasure chests for beetles, birds and maybe even amphibians. They would recognize the biological signatures of Loxodonta africana africana (bush elephants) and Loxodonta africana cyclotis (forest elephants), signatures as ubiquitous as urban graffiti in the 80s, made by creatures sometimes as elusive as Banksy.

Signs of the invisible giants loiter everywhere: A watering hole where a baboon sits and drinks, the hole created when a thirsty elephant digs its trunk into a dry riverbed. The straw bird houses swinging in the acacias; weaverbirds pluck the fibers from elephant dung to build nests in the thorny trees with umbrella canopies that speckle the landscape. Hulking vegetarians dine on acacias, pruning them and denying them any chance at dominating the country, creating space for the grasses grazed by zebras and other ungulates. The spiny succulent Sansevieria—elephants’ chewing gum—pokes out of the earth, spread around by the elephants lumbering through patches, breaking off bits as they chomp the fat, rounded leaves for moisture, spitting out a tangled fibrous ball. The Samburu use the leaves for ready-made bandages or pound them to a pulp to liberate the fiber for rope making.

What does a landscape without Proboscidea look like? Mihlbachler walks over to his computer. He searches for two side-by-side images: one of a dense forest, the other a shrubby grassland.

“What Americans view as a pristine habitat is probably a sort of a distortion, where the vegetation is far denser and more overgrown than what those places have been like for millions of years,” Mihlbachler says. “This honestly has a cascading effects on other organisms.” He points to one landscape. “Different kinds of species are going to be able to live there,” he says, and then points to the other landscape, “as opposed to there, plain and simple.”

One landscape is closed, dense, with more uniform vegetation—a paucity of plant species that affects biological diversity and biomass in unseen ways. Beetles, for example, declined in species diversity and number in European forests when the giant herbivores went extinct in the early Holocene, about 10,000 years ago.

The other, browsed, landscape is mosaic of grasses, shrubs, and trees, a biological mish-mash of vegetation that supports a richer, more diverse ecosystem. Big herbivores have big effects on plants, tearing into their communities, creating gaps, dispersing seeds and nutrients in big deposits of dung and urine. That is why some ecologists have led “rewilding” campaigns that include re-introducing key megafauna to various habitats.

Re-establishing wilderness in our world may require bringing back Proboscidea to help recreate healthy and diverse ecosystems like the one humans evolved in, and like Kenya today.

Jude Isabella is a science writer based in Victoria, British Columbia. Her new book, Salmon, A Scientific Memoir, will be released next year.