1 How We Think About Animals Has a Long, Complicated History

Back when I first started writing about scientific research on animal minds, I had internalized a straightforward historical narrative: The western intellectual tradition held animals to be unintelligent, but thanks to recent advances in the science, we were learning otherwise. The actual history is so much more complicated.

The denial of animal intelligence does have deep roots, of course. You can trace a direct line from Aristotle, who considered animals capable of feeling only pain and hunger, to medieval Christian theologians fixated on their supposed lack of rationality, to Enlightenment intellectuals who likened the cries of beaten dogs to the squeaking of springs.

But along the way, a great many thinkers, from early Greek philosopher Plutarch on through to Voltaire, pushed back. They saw animals as intelligent and therefore deserving of ethical regard, too. Those have always been the stakes of this debate: If animals are mindless then we owe them nothing. Through that lens it’s no surprise that societies founded on exploitation—of other human beings, of animals, of the whole natural world—would yield knowledge systems that formally regarded animals as dumb. The Plutarchs and Voltaires of the world were cast to the side.

The scientific pendulum did swing briefly in the other direction, thanks in no small part to the popularity of Charles Darwin. He saw humans as related to other animals not only in body but in mind, and recognized rich forms of consciousness even in earthworms. But the backlash to that way of thinking was fierce, culminating in a principle articulated in the 1890s and later enshrined as Morgan’s Canon: An animal’s behavior should not be interpreted as evidence of a higher psychological faculty until all other explanations could be ruled out. Stupidity by default.

At roughly the same time a similar dialogue played out in popular culture in the United States: the so-called Nature Fakers controversy, which pitted best-selling naturalist authors who wrote about the intelligence of animals against prominent natural historians—and, famously, President Theodore Roosevelt—who denounced the naturalists as charlatans. The latter side prevailed, pushing a belief in thinking, feeling animals to the margins of our cultural ideas about nature. This belief was never fully extinguished, but was treated as unserious, the stuff of children’s stories and fiction, even as the presence of cats and dogs and other animal companions in our day-to-day lives showed how ridiculous it was to think of them as unintelligent.

As recently as the late 1970s, when zoologist Donald Griffin proposed that animals could think and reason, most scientists treated it as a radical claim. But the science has grown by leaps and bounds in the half century since then; the notion that all animals are conscious is today considered a serious—I would call it uncontestable—claim. That’s where we are now, and as a society we’re thinking through what that means for our relations to other creatures and the categorical lines we draw between them.

2 The Science of Self-Awareness Has Shifted Radically

Try to imagine yourself without a sense of self. To me, that’s like a Zen koan, paradoxical and irresolvable: the knowledge that I am myself, an entity separate from other individuals and my surroundings, the subject of my experiences, is so fundamental that I can’t conceive otherwise. I wouldn’t even call it knowledge. It’s a baseline human condition.

Yet the self-awareness of other animals has been a scientifically controversial subject. For decades the gold standard of measurement was the mirror self-recognition test: whether an animal could use a mirror to find an otherwise hidden mark on their body, and then investigate it. That suggested a conflict between their mental image of themselves and the image in the mirror. They were self-aware.

Even a bee sipping nectar takes pleasure from the meal.

A few species other than humans pass the test: orangutans, chimpanzees, Asian elephants, bottlenose dolphins, and perhaps magpies, manta rays, and cleaner wrasse. Other creatures, then, are sleepwalking through life, a biological version of the wind-up toys to which René Descartes likened animals—unless there’s more to self-awareness than the mirror test.

Some scientists say that it puts too much weight on sight, which is less important to many species than it is to us. From this perspective emerges experiments like one used to show how dogs, who don’t recognize themselves in mirrors, do recognize their own scents. This has been demonstrated with garter snakes, too—which is a finding I love because it brings reptiles, a class of animals whose intelligence is usually overlooked, into the conversation. Their self-image may be a self-odor.

Others argue that a sense of self should be understood, in the words of the late ethologist Frans de Waal, “like an onion, building layer upon layer.” Our own self-awareness contains many cognitive layers—of memory, metacognition, language, and so on—and is perhaps unique in the extent to which we reflect upon ourselves, but those capacities are found in various forms and configurations across the animal kingdom. And at the center of these layers is a more fundamental form of self-awareness, produced when perceptions are integrated with a mental representation of one’s surroundings. That sort of selfhood is ubiquitous among animals.

This shift in our understanding is a truly revolutionary development. To think of every creature as a someone, living in the first person, with whom we share this fundamental property of our own experience of life, isn’t unscientific anthropomorphism. It’s where the science is pointing us.

3 Animal Life Is Full of Satisfaction

“The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation,” wrote Richard Dawkins in River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life. “During the minute it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive; others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear; others are being slowly devoured from within by rasping parasites; thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst, and disease.” Some seasonal abundance might offer respite, but only briefly, “until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored.”

Dawkins expressed a fairly common view of nature. We might not articulate it to ourselves in such stark terms, but there’s a tendency to think that wild animal lives are characterized by pain and privation. This is often used to rationalize the exploitation of captive animals: They might be bored and miserable, but at least they’re fed. More recently, some philosophers have argued that we should be glad to see predators eradicated; after all, a world without them would contain far less suffering. They’ve even floated the idea that habitat destruction isn’t such a bad thing, as it prevents future suffering.

Dogs, who don’t recognize themselves in mirrors, do recognize their own scents.

Many people understandably find these ideas repulsive. Perhaps surprisingly, they don’t bother me very much: They represent an attempt to reckon with the reality of suffering. If life as a wild animal were truly so horrible, nature would be a dark place indeed. Even the appreciation of warbler’s song would come with sadness—but that totalizing emphasis on the negatives misses the many positives, the pleasures and joys, that animal life contains.

Research shows that even a bee sipping nectar takes pleasure from the meal—and not only in the moment, but in the ongoing state we call happiness. I like to think of the gustatory delights experienced by other animals as they eat: What sensations await a muskrat whose diet is comprised of dozens of species of plants consumed at different times of year? Even something as basic as making a choice seems to be intrinsically rewarding. And then there are the satisfactions of companionship—with mates, with offspring, with friends. Humans experience something called the social buffering effect, in which negative sensations are dulled by the presence of others; there are studies on this in animals, too, such as lake sturgeon who are less bothered by extreme water temperatures when other sturgeon are around.

As for that warbler, research suggests that the act of singing can be pleasurable for birds, with a little flush of dopamine accompanying each correct note; and though that warbler may well end up in the belly of a squirrel, and the squirrel in an owl, the threat of predation may not be so awful as we think. Ecologists describe how predators create a “landscape of fear,” with their presence affecting the activities of their prey—but this might better be understood as a landscape of risk, in which animals don’t live in constant fear but pragmatically adjust their movements.

All this is just a sampling of the research that exists, and might yet be conducted, on the experiences of animals. The neurobiologist Simona Ginsburg and evolutionary theorist Eva Jablonka speculate that even the simplest animal life has a slightly positive valence: Merely being conscious and in the world feels a little bit good. That’s how evolution keeps us going. Far from being unrelentingly bleak, the lives of animals contain, as do ours, a great many pleasures. ![]()

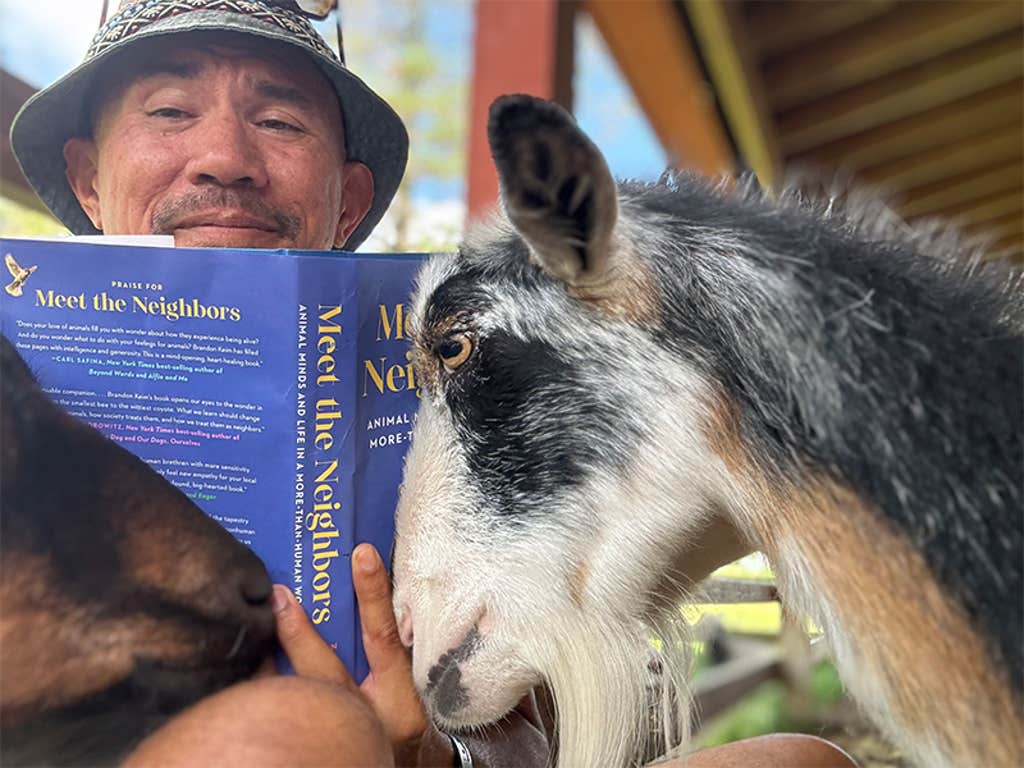

Read an excerpt from Brandon Keim’s new book, Meet the Neighbors, here.

Lead image: Jolanda Aalbers / Shutterstock