Scuttling through the brush in the dark of a Dominican Republic night, a rare Hispaniolan solenodon comes into view in the sudden beam of a flashlight. This small animal has an exaggerated shrewlike snout and is one of the few venomous mammals on Earth. Hispaniolan solenodons (Solenodon paradoxus) live mostly off of insects, seeking protection in their burrows during the day and foraging at night. But their numbers are few, and their species status has been fragile.

One of only two surviving endemic mammals on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, the solenodons and their future depend disproportionately on conservationists in the Dominican Republic. With the island’s other nation of Haiti in dire political and economic straits, conservation work for the solenodon has largely fallen on the eastern nation’s shoulders.

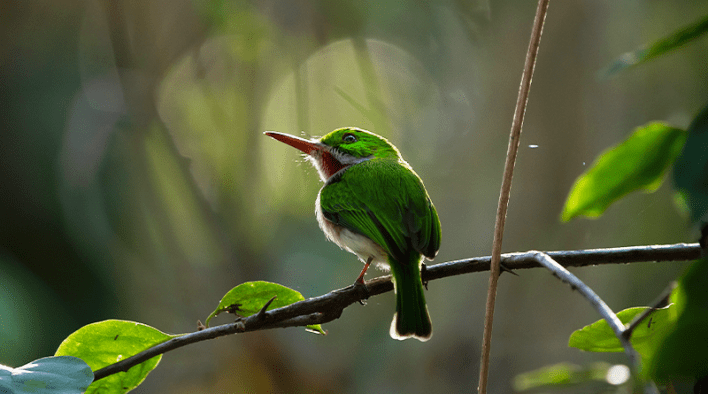

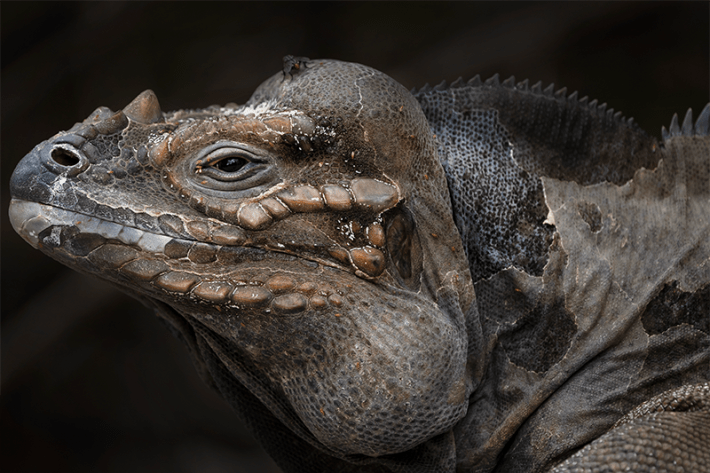

As it has for many of the island’s other unique endemic species. From the strikingly jewel-toned broad-billed tody (Todus subulatus) to the charismatic endangered rhinoceros iguana (Cyclura cornuta), animals of Hispaniola have been facing pressures from agriculture, poaching, development, feral predators—and collisions with humans: The Dominican Republic alone, with a population of just over 11 million people, hosts more than 7 million tourists each year.

Islands and their endemic species have long been essential in helping us understand evolution. Since Charles Darwin’s 19th-century visit to the Galapagos Islands and his observations of their now-famous finches, with their niche-hewn bills, scientists have relied on unique island animals to help piece together the winding tale of speciation. Now islands are showing us a new side of change: the impact human interference has on endemic species’ evolutionary trajectories. Island animals are uniquely vulnerable to encroachment. “A high jeopardy of extinction comes with territory,” David Quammen writes in The Song of the Dodo. “Islands are where species go to die.”

But it doesn’t have to be that way. Working to protect their local species, Dominican Republic conservationists have spent decades diligently dismantling poachers’ traps, tracking populations, and fighting to protect key habitat from development. With all of this work, animals like the Hispaniolan solenodon and the rhinoceros iguana now might have a fighting chance at a long future.

As a wildlife conservation photographer, I had the fortune of visiting the Dominican Republic last year and venturing out alongside some of these conservationists to document their work—and the striking animals they are helping to protect.

Despite their endangered status, rhinoceros iguanas are still sometimes captured for human consumption in Haiti—and often eaten by feral dogs, cats, and mongooses throughout Hispaniola. But at Lago Enriquillo National Park in the southwest of the Dominican Republic, the lizards are free to roam in relative peace. Eating plants and warming themselves in the arid landscape, they can grow up to 4.5 feet long and weigh up to 20 pounds.

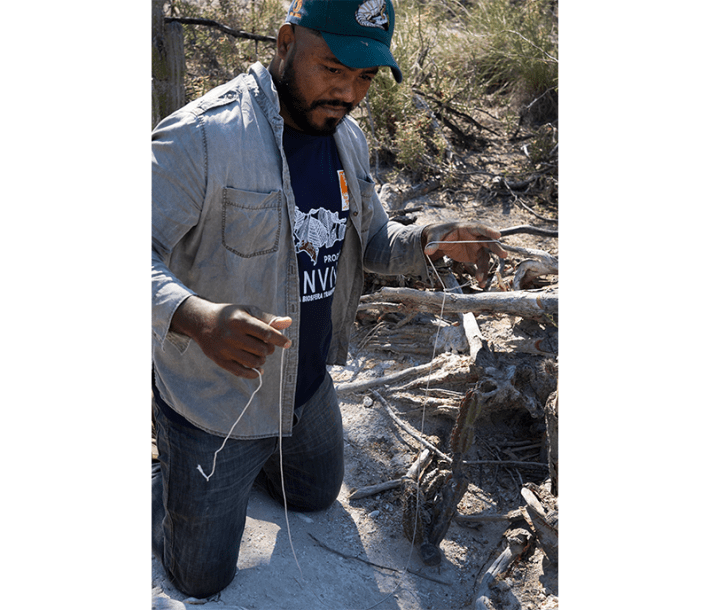

But even here, within the park’s protected boundaries, I learned that the iguanas are not entirely free from human-caused hazards. The area is riddled with makeshift traps set by poachers, jury-rigged from string and logs, poised to ensnare the iguanas emerging from their dens.

Dedicated park rangers, including Jerbin Volquez and many others, are working hard to clear these traps and save more of the imperiled individuals. We spotted one such trap right after entering the park, which Volquez quickly disassembled. “When the iguanas come out of their dens, they get caught up in the strings,” he explained. Although the poachers typically capture the iguanas live to sell as pets or in the exotic animal trade, “sometimes the poachers take too long to come back and check their traps, and the iguanas starve to death.”

Other threats to these even-keel iguanas come in the more innocuous form of curious tourists. As people flock to the park’s stunning saltwater lake, they encounter these vegetarian lizards and offer them snacks. Such routine feeding has made rhinoceros lizards not only unwary of humans, but also increasingly sick from eating their food.

Another danger is apathy from national authorities, which continue to authorize developers to build in or around the habitats of these animals outside of the park, further reducing their crucial homeland.

The solenodon is a curious animal, a relic of sorts, and has been darting along its own evolutionary path since the late Cretaceous, when giant Lambeosauruses were tromping about Mexico. Although solenodons were common throughout North America millions of years ago, they now persist only on the islands of Hispaniola and Cuba. Their long history allowed them the time to develop their own venomous hunting strategy—a newly cracked case of convergent evolution.

Since their first scientific description in the mid-19th century, the Hispaniolan solenodon’s status has wavered between functionally extinct and unconcerning. Part of the challenge is in finding the animals.

A nighttime trip to Sierra de Bahoruco National Park and the guidance of its head ranger, Nicolás Corona made it possible on my visit. Colá, as Corona is known locally, had just finished fighting a wildfire nearby and was eager to help us check in on the impact on his beloved solenodons.

Although Colá was once a hunter, he eventually found more purpose as a park ranger. He has now been working to protect Hispaniolan solenodons for three decades and has made a name for himself as one of their key experts in the international scientific community, appearing in the acknowledgement section of countless journal papers about the animals. In part because he has a special acuity for finding these elusive animals.

Like the hunter he once was, he waits, in quiet darkness, until he hears the tiny steps of the solenodon on the leaf litter. Their odd zig-zag traveling pattern makes their footfalls easy to distinguish from other small quadrupeds. Once he can sense the animal is near, he flashes his light on them, causing them to freeze in their tracks—and allowing him to carefully pick them up for any examination or research before releasing them.

The night of my visit, Colá and his fellow rangers, still covered in soot from their firefight, instructed us to turn off all lights and wait, while they ventured quietly into the woods. In less than 40 minutes, we heard a whistle and saw Colá and his team emerge from the woods. “We found two! A male and a female!” he shouted with a huge smile on his face, which was now relaxed with relief that the nearby fire hadn’t decimated the local population.

In 1981, the Hispaniolan solenodon was declared functionally extinct, and as recently as 2020 it was considered endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. But thanks in large part to the work of Colá and his colleagues, the IUCN has recently promoted it to “least concern.” But due to concern over its populations outside of the park, the Dominican Republic government still qualifies the unusual mammal as endangered to bolster conservation efforts.

Despite their successes, conservationists in the Dominican Republic remain concerned about the future of their endemic species in the face of the country’s growing tourism industry. New hotels and tourism complexes continue to be built on delicate habitat. Still, Corona, Volquez, and countless other dedicated rangers and advocates continue to fight for these iconic wildlife species. ![]()

Tamara Maria Blazquez Haik is a conservation photographer and environmental educator from Mexico City, a Sony Alpha Partner and IUCN-CEC Member. Her goal is to aid in nature and wildlife conservation, both in Mexico and internationally, through her photography, journalism, speaking and educational skills.

Lead photo by Tamara Maria Blazquez Haik.