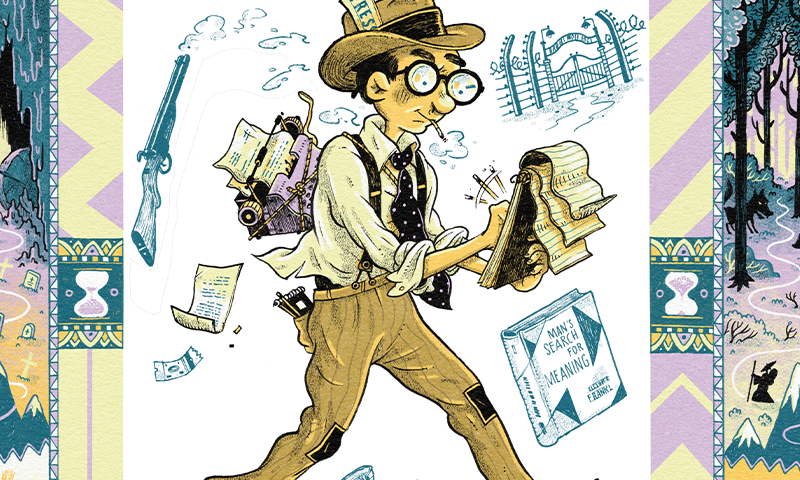

In 1939, at the age of 27, Sid Kline set sail for Europe, landing in Prague as the Nazis were on the march. The night before their arrival, he stood on a balcony with Czech aristocrats and helped them polish off their best champagne, then smashed the crystal glasses in the courtyard below so nothing would be left for the Nazis.

In the days that followed, Sid, the short-statured son of a Jewish shoe salesman from Camden, New Jersey, visited Berlin, rubbing shoulders with currency smugglers, mercenaries, and his fellow American correspondents. He traveled by train through treacherous border crossings, and smuggled a subversive manuscript penned by a Count into free territory. He returned home to Manhattan to settle down, married my grandmother, and soon after, my mother arrived.

By the time I came along, Sid had lost most of his hair, developed a healthy paunch and a hearty smoker’s laugh, and taken a job as a rewrite man for the New York Daily News, where he wore a rumpled shirt and a green eyeshade, chain-smoked cigars, and spun reports coming in from the far reaches of the world’s greatest city into narrative gold.

Anyone can have a hero's journey if you think about your life in a new way.

Sid used to tell me he couldn’t imagine a more satisfying life than the one journalism had provided him—the stories he heard, the people he met, the adventures it afforded him. It was a life story that allowed Sid to live out his final years believing himself to be a blessed and grateful man.

I thought of Sid earlier this year when I read the psychology paper, “Seeing Your Life Story as a Hero’s Journey Increases Meaning in Life.” The title struck something inside me I knew to be true. It began with Sid, whose hero’s journey increased meaning in my life—certainly more than the one offered by my other grandfather, a scientist who died far richer and with more renown but lacked Sid’s talent for storytelling. But it’s something I’ve also seen in countless others over the course of a long career traveling far and wide and speaking with people from all walks of life.

Sid’s stories led me to become a journalist. They’re the reason, when I reached my mid 20s, I quit a safe, secure job covering the New Jersey congressional delegation for a regional newspaper in Washington D.C., ignoring the warnings of my older colleagues who suggested my career would never recover. I felt stifled by the background politicking, calculations, and grandiosity of those in official Washington, a bubble where even the most extreme problems and high-stakes stories were somehow made to seem bloodless, bureaucratic, and disembodied from real human drama.

So, at 27, I moved to Cambodia, a raw, traumatized nation still emerging from 30 years of civil war, where everyday life seemed to be a matter of life and death. I wanted to meet and write about people who didn’t have the option of a safe, predictable life. I wanted to be surprised. I couldn’t ignore the ghost of Sid Kline—I wanted to have adventures.

And I have. I’ve pursued stories about people who, through the whims of fate, their own choices, or a combination of both, have found themselves in extreme situations that most of us can hardly imagine. Often the stories that are the most dramatic take a psychological toll on those involved. And often they’ve led me back to a series of questions that have long preoccupied me. How do people find meaning in the face of unimaginable tragedy, trauma, or disappointment? Why do some self-destruct, lose touch with reality, or give up, while others survive, recover, and find ways to draw strength from the challenges they were forced to endure?

Again and again, I found the answers zeroed in on the stories people told about themselves. During my interviews with genocide survivors in Cambodia, Vietnam veterans tormented by visions of their friends being obliterated in battle, victims of terrible accidents, survivors of workplace shootings, gang members in California’s most notorious prison, I saw up close how important the hero-journey narrative, or something close it, was to them, transforming and even helping to save their lives.

Seeing Your Life Story as a Hero’s Journey” is written by Kurt Gray, a social psychology professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Benjamin Rogers, an assistant professor in the Management and Organization Department at Boston College’s Carroll School of Management, along with eight colleagues in psychology. The authors were originally inspired by a screenwriting book, Into the Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them. Into the Woods author John Yorke writes that what makes a good movie is not necessarily the elements of the plot itself. What matters most is the growth and evolution of the characters at the center of that plot.

Gray chanced upon the book while going through a period in his own life when he felt purposeless and depressed. Nothing he could imagine doing seemed sufficiently epic. Perhaps, he thought, what was true about stories in movies and books that moved us was also true for our life stories. Maybe the problem was not that his life lacked meaning. Maybe the story Gray was telling himself about his life just needed a rewrite. “As human beings, we all grapple with meaning,” Gray told me. “Maybe my life could be more meaningful or less meaningful depending on how I think about it. We have this mind built for storytelling. We understand the world in terms of stories. And if that’s true, what stories are the best?”

In the paper, Gray, Rogers, and their colleagues unveil a “re-storying” intervention designed to help people transform the way they view their life stories—an intervention the paper suggests that can increase both meaning and resiliency in the face of life’s challenges. The authors designed their intervention by drawing from the “hero’s journey,” a classic story arc first identified in the 1940s by Joseph Campbell, the late scholar of comparative religion.

Each one of us is wired to behave like an autobiographical author—to make sense of the world through our stories.

Campbell, influenced by the ideas of the spiritual psychoanalyst and Freud disciple Carl Jung, argued that universal elements could be found in the most enduring myths and fairytales of disparate, unconnected cultures across the globe since the beginning of recorded history. This suggested to him that human beings are wired to make sense of the world around them by placing them in the context of this innately satisfying narrative structure, which Campbell detailed in his seminal 1949 book The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

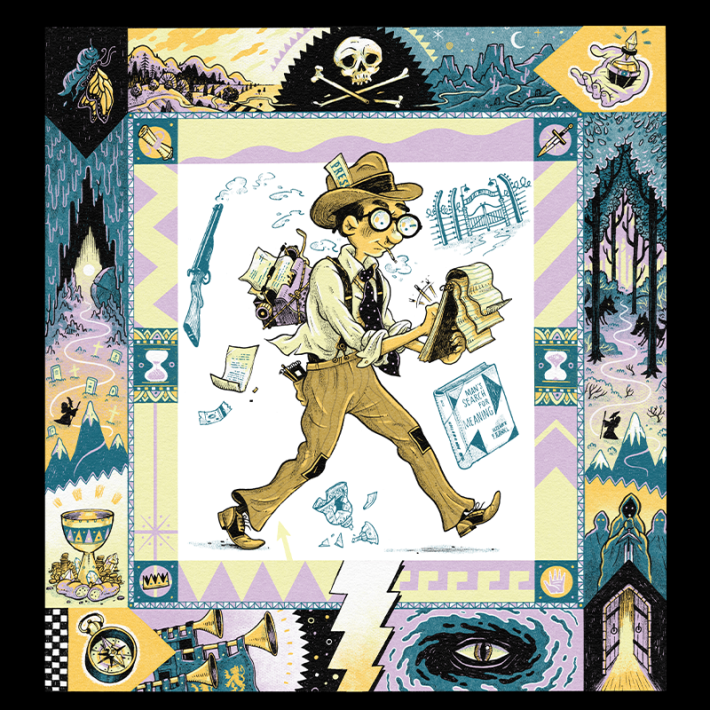

Stories as diverse as the Odyssey, Ramayana, King Arthur, and even the Bible, Campbell argued, each contained a series of recognizable stages that began with a “call to adventure,” and led to a transformative quest. Along the way, the protagonist received help from mentors, encountered allies and enemies, and overcame a series of trials before achieving success and returning home transformed. Famously, George Lucas has said he based Star Wars on The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

Gray, Rogers, and their coauthors boiled down Campbell’s 17 stages of the hero’s journey to seven: protagonist, shift, quest, allies, challenge, transformation, legacy. They created a psychological test for people to measure the presence of those elements in their lives. Those who saw their lives as an epic journey scored higher on tests designed to measure meaning in one’s life and the psychological elements associated with it—satisfaction, a sense of well-being, and the extent to which they were “flourishing.”

“The hero’s arc connects the events of your life together, not just into different episodes, but one coherent narrative—and meaning is ultimately about connection, connecting up to bigger things, connecting together,” Gray explained to me. “Not only does it connect it together to something bigger, but it connects it together into something that resonates with us and is as timeless as we see in the movies.”

Gray told me he managed to put his crisis of meaning behind him. Though he recognizes that having kids is not saving the world, and “sitting by the playground is not as exciting as running from the black riders from Lord of the Rings,” he said he is determined to take new challenges in his professional life and make new allies in his personal one. “The point is,” he said, “anyone can have a hero’s journey if you think about your life in a new way.”

One of Gray’s heroes, and a coauthor of the Hero’s Journey paper, is Dan McAdams, a professor of psychology at Northwestern University. In the field known as “narrative psychology,” McAdams is a Jedi Master—a pioneering theorist who drew together intellectual strands from multiple fields to help invent a new one in the 1980s.

A trim, bespectacled psychologist with a square jaw, and thick, gray hair that he wears swept back over a broad forehead, McAdams told me his ideas about narrative psychology grew out of his experiences as an assistant professor at Loyola University, introducing undergraduates to the work of Erik Erikson, the 20th-century psychoanalyst best known for his theories of psychosocial development.

Erikson suggested human personality development proceeded in a series of predictable stages, each one characterized by a key challenge; young adults like his students, Erikson maintained, and McAdams taught, were primarily concerned with the crucial task of forming a coherent identity. (Erikson is credited with creating the phrase “identity crisis,” and a failure to complete this phase of development results in “role confusion.”) Among McAdams’ influences was French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, who argued humans came to understand their own identities by using language to draw together disparate events and establish causal and meaningful connections between them.

That conclusion has powerful implications, McAdams said. Psychologists have long argued that identity provides the compass that, as we grow older, we use to guide our journey through the world and understand our place in it. Our identity determines which groups we seek out when we feel threatened or anxious, it determines which ideas we will defend, fight for—even die for. It also molds our expectations, and directly influences our choices and actions.

For McAdams, an intellectual breakthrough came when he began to realize that stories weren’t just a means to help form identity—story and identity were the same thing.

“If you could see an identity, it would be a story,” McAdams said. “People have stories in their heads about how they came to be and where their lives are going. A story does all those things that Erikson said that identity should do. It puts your life together, past, present, imagined, future, beginning, middle, end. It links things together over time. It integrates different parts of yourself.”

Each one of us, McAdams said, is wired to behave like an “autobiographical author”—to make sense of the world by creating stories about our lives. These stories “sit in our heads and they give our life a sense of purpose and meaning.”

Some view their lives as tragedies. Others, comedies, or love stories. Some stories are as labyrinthine as a Dostoevsky novel, others as simple as Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. The way that people organize the events of their lives can reveal their level of resilience and influence the way they deal with adversity.

It’s a theory that is now supported by a weighty body of research. McAdams has spent decades sitting with strangers, collecting their stories, then teasing out patterns and correlating those patterns with standard measures of personality, well-being, and other variables.

McAdams today is best known for his work studying the stories of adults between the ages of 40 and 65, a period of life where the tumult and uncertainty of youth has dissipated, and healthy individuals—at least the way Erikson saw it—are often focused outward, raising children, enmeshed in careers, and being active in society. The healthiest adults, Erikson suggested, had mastered what he called “generativity,” they had developed a propensity to engage in acts that contribute to the greater well-being, and often promote the well-being of younger generations.

Indeed, McAdams found that, in middle-aged adults, just as Erikson theorized, there was a strong association between a deep sense of meaning, connection, and psychological well-being and generativity. The stories those generative people told, McAdams discovered, often shared common elements—elements prominent in the hero’s journey—about overcoming suffering, triumphing over adversity, or being delivered from pain and persecution and turning challenges and setbacks into something positive.

“Highly generative adults love to tell you about their lives, almost as if they take pride in bad things happening,” McAdams said. “They love to tell you about how they turned the bad stuff into good stuff.”

McAdams also found common themes in the stories of those on the opposite end of the spectrum at middle age—those who instead of mastering the challenge of generativity had fallen into despair. Many of them believed that their most important life experiences were guided by fate, luck, and other circumstances beyond their control. McAdams coined the term “contamination” to describe a story element often seen in stories associated with the most miserable.

“Contamination means you have really great scenes that go suddenly bad and you can’t undo them,” he said. “If you have a bunch of them, or if you tend to see life that way, it’s trouble. Even if you have a positive event, you’re expecting the other shoe to drop. You’re expecting contamination. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

I asked McAdams whether his findings, based for the most part on white populations in colleges and universities, applied to non-white, non-educated, non-American populations. He acknowledged that early in his career, he shared my concerns, and wondered whether his samples had skewed his findings.

But, he said, “we have never found any kind of relationship between education, income, and the ability to tell narrative stories about your life. Granted, we are not studying people who are homeless on the street, but we have looked at a broad range, from working class to upper class. The dimensions we look for—redemption, agency, communion, coherence—are not related to demographic variables. They’re not related to race either. We’ve done a lot of work with African Americans and contrasted them to Euro-Americans, and you don’t see big differences. Storytelling is basic. People respect stories and tell stories in all cultures.”

When I arrived as a new reporter in Cambodia, the country was still grappling with the legacy of three decades of civil war. Within a few days, I found myself interviewing—and working alongside—survivors of genocide. Most of the people I met had lost members of their family under the Pol Pot regime, a cataclysmic four-year period between 1975 and 1979 during which one in four Cambodians died of murder, starvation, or disease. Others had served as child soldiers, ended up in refugee camps, and suffered other traumas as the nation endured, not just a genocide, but a decade of a Vietnamese occupation, and a protracted civil war that kept Cambodia in poverty and crisis.

I saw things that left me shaken. I met an elderly woman begging on the street, who burst into tears when I asked her if she supported a United Nations tribunal to try former members of the Pol Pot regime, even though some were warning it could shatter the fragile peace. As tears streamed down her deeply lined cheeks, she described how Khmer Rouge soldiers had murdered her children in front of her by throwing them down the stairs. “They killed my children and that is why I am like this,” she said. Decades later, she still yearned for vengeance. The chance for justice was worth any cost.

But I also saw things that left me inspired. One day, I traveled up to the Thai border to visit a recently liberated former Khmer Rouge stronghold deep in the Cambodian jungle. For 30 years, music had been banned and the villagers had been forced to dress only in gray and black. I arrived to find them clad in gaudy shades of pink, purple, and yellow—a joyous explosion of clashing colors, so jarringly mismatched it would have given Tim Gunn a heart attack. Later, sitting on a simple platform made of wooden slats, I listened as a woman told me about the day, just a few weeks earlier, when an enterprising countryman brought the first karaoke machine to town. Nobody had any money to pay for a song. But people came from miles around just to see it. And when that first maudlin Thai video flashed on the screen, depicting two young lovers by a riverbank crooning to one another in the melodic phrases of a contemporary pop song, the entire village burst into tears moved by the beauty of the simple cinematic and musical experience.

“They killed my children and that is why I am like this.”

It was in Cambodia that I first became fascinated by the phenomenon of psychological resilience. That led me to the classic book, Man’s Search for Meaning, by the Austrian psychiatrist and Nazi death camp survivor Viktor Frankl, a book that, long before the hero’s journey paper came out, presented a “re-storying intervention” that convinced me and a lot of others too, that when people change the way they view their story, it can change the way they live their lives. Both Gray and McAdams told me Frankl’s book had a profound influence on them.

At Auschwitz, Frankl observed his own physical and spiritual decline with grim professional detachment. He was called upon to counsel his fellow prisoners who had been pushed past the limits of their physical, psychological, and spiritual endurance. Frankl faced an impossible challenge. What is there to say, Frankl writes, to someone trapped in a real-life nightmare who insists, “I have nothing to expect from life anymore”?

Frankl’s approach was to convince those in despair they could still be a hero in their own story. The death camps show that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

“The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the sufferings it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity—even under the most difficult circumstances—to add deeper meaning to his life. It may remain brave, dignified, and unselfish,” Frankl wrote. The impact of this shift in thinking, Frankl argued for the rest of his life, could transform lives. Like the life of Manuel Ruiz.

I met Ruiz in San Francisco in 2018, while researching a story on Inside Circle, a national organization that helps men inside and outside of prison rediscover their humanity, heal, and find purpose by offering group therapy seminars. During the gang hysteria that gripped Los Angeles in the early 1990s, Ruiz was convicted of shooting a rival gang member (who survived) and sentenced to life in prison. He arrived at California’s Folsom Prison as a confused 19-year-old kid with no education, full of self-loathing, hopeless, “lost,” violent, and defiant.

Within three months of arriving at Folsom, Ruiz was sitting in the day room watching TV, when older members of the Mexican-American prison gang with which he was associated approached and asked him if he’d be willing “to put in some work” for them in the prison yard. The Mexican Americans were at war with the Black inmates, and while the gang leadership had been serving time in solitary for fighting, five Mexican-American inmates in non-leadership roles had negotiated a truce with the Black inmates without their authorization. The older members wanted Ruiz to “send a signal.” They told him to carry out a nonfatal stabbing of one of the Mexican-American inmates who’d violated protocol. A couple days later, they sent him out into the prison yard with a knife made of sharpened metal taken from a clipboard, clenched between his butt cheeks. They also gave him an “ass-pack” consisting of a latex glove stuffed with tobacco, drugs, and messages to insert like a suppository in the expectation he would get sent to solitary confinement, “the hole.” Ruiz carried out his duty. He stabbed an older Mexican-American boxing trainer in the neck.

“I was sitting with the acceptance that I'm going to die in prison.”

Ruiz got 16 months in the hole for the stabbing and began a violent journey that would land him in Pelican Bay, the supermax prison whose inmates included Charles Manson and Sirhan Sirhan. It was there that Ruiz discovered Frankl’s book, sent to him by his mother, and was introduced to older inmates who encouraged him to better himself.

Ruiz began waking up at 4 a.m. in his cell, doing yoga and tai chi, and working out. He refrained from cursing, forcing himself to do 50 burpees every time he slipped. He started doing crossword puzzles to improve his vocabulary. He avoided drinking and doing drugs (widely available in prison). He began to read, to study, to improve himself physically, mentally, and spiritually. He made a life for himself within the walls of his prison. (During the COVID-19 epidemic, during lockdown, he gave me advice on how to get through it without sinking into a deep depression.)

Ruiz told me he was determined to change his narrative, to become a hero of his own story. He began to think of himself as a “spartan,” a “warrior,” a man of substance and dignity. “I was sitting with the acceptance that I’m going to die in prison,” he said. “I’m not going to be able to see my parents. My whole reality was, ‘This is it, this is my life. What do I do?’ I knew Frankl went to the concentration camp, lost his wife. And his ability to change his perspective in the midst of that shit was a freaking huge deal. It was a big influence on me.”

By the time Ruiz left prison more than 21 years later, the unexpected beneficiary of recent prison reforms, he had transformed into an educated, leading advocate for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated men. Today he is the chairman of the board of Inside Circle.

Dennis Charney was also influenced by Man’s Search for Meaning, though when he read it, he had little reason to suspect the lessons contained in the book would ever apply to him.

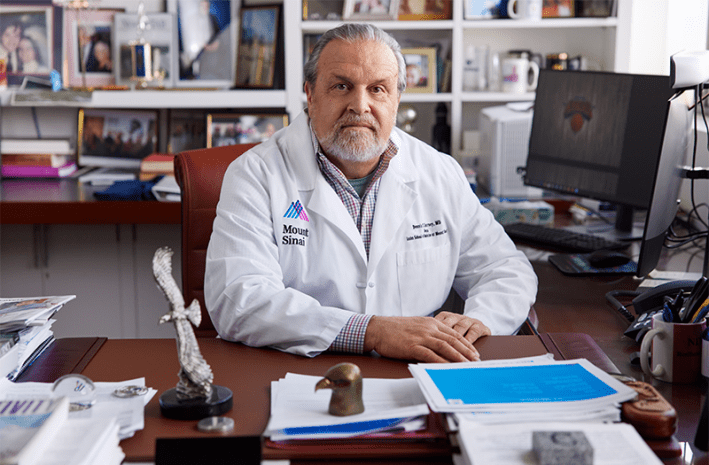

Charney, who today is the dean of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, is an expert on resilience. He spent more than 30 years studying victims of sexual and physical abuse, those with congenital diseases, survivors of earthquakes, and prisoners-of-war from Vietnam who’d been kept in solitary confinement for years.

On Aug. 16, 2016, a former employee lay in wait for Charney outside his favorite delicatessen in his hometown of Chappaqua, New York. When Charney emerged with his morning bagel and cup of coffee, the employee, a disgraced scientist fired by Charney for scientific misconduct, opened fire at close range with a 20-gauge shotgun. The shotgun blast tore apart Charney’s right shoulder, punctured a lung, peppered his liver with buckshot pellets, and caused him to lose half his blood.

After six days in intensive care, Charney returned home, so spooked he slept with the light on. He endured waves of anxiety and fear, and fought off the instinct to hate his attacker, recognizing it as “negative energy that drags you down.” Early in his convalescence, he said, he recognized the opportunity to implement the lessons learned over his years of research. “You look at what happened to you, and you realize that you can’t undo what happened, but you can reframe it,” Charney said. “You can assimilate it into who you are as a person and move forward.”

Charney’s road to recovery, just like the transformation of Ruiz, seemed to follow the steps of the hero’s journey. Charney cast himself as a protagonist on a quest to assimilate the shooting into his own story. He told me he had lost a grandchild to a genetic disorder. “Those things become part of your life story,” Charney said. “The great things, the loves of your life, and the traumas, come together in your life story. How you handle them contributes to your personal growth. The term we use in my field is ‘post-traumatic growth’—you grow from the trauma and that makes you prepared to handle other challenges in your life.”

When Charney emerged from the deli, the disgraced scientist opened fire with a 20-gauge shotgun.

Following the shooting, Charney identified obstacles and challenged himself. A competitive kayaker and weightlifter, he resolved to recover sufficiently to enter a kayak race by the following spring and compete with med students in an annual “strongest person competition.” He relied on allies—family, friends, doctors, and students for physical and emotional support. He embraced a legacy, seeking out other victims, sharing his wisdom and offering support.

“My recovery was very public because I’m the dean, and I was in the ICU of my own hospital,” Charney said. “And what I did for myself was realize I could be a real role model for other people because so many people were watching my recovery.” Charney coauthored the 2012 book Resilience: The Science of Mastering Life’s Greatest Challenges, with Steven Southwick, also an expert on human traumatization. Southwick died of prostate cancer while writing the third edition. Southwick’s battle against cancer, Charney said, “ended up becoming part of his life story, his narrative. He fought heroically for five years.”

We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Joan Didion famously wrote in 1979. “We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ‘ideas’ with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.”

Didion’s loss of faith in “narrative’s intelligibility” is a pronounced theme today. “We’re told that story will set us free. But what if a narrative frame is also a cage?” asked The New Yorker in a 2023 essay, “The Tyranny of the Tale.” Kieran Setiya, a professor of philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, takes up the reasoning that imposing a narrative line on our lives reduces them in his 2022 book, Life Is Hard: How Philosophy Can Help Us Find a Way. “When you define your life by way of a single enterprise, a narrative arc, its outcome will come to define you,” Setiya writes. “It’s a tendency we should fight.”

I was curious what Setiya might think of the hero’s journey paper. When I described it to him in an interview, he had quick rebuttals. “If you’re thinking of your life in narrative terms, you risk setting yourself up for a kind of life-defining failure,” he said. “You can narrow your perspective on life. You might think that making sense of your life in terms of a story can be meaningful and valuable and help you come to terms with difficult experiences. But that doesn’t have to take the form of a linear narrative of the kind the hero’s journey suggests. Lots of people have good lives without telling that kind of hero narrative.”

What’s more, Setiya said, “There’s the idea that if you can adopt the right attitude toward whatever circumstance you find yourself in, giving up on what’s out of your control, focusing on what’s in your control, and directing your agency at that, you’re guaranteed to achieve a flourishing or meaningful life. I don’t think that’s true. I don’t think there’s any guarantee, unfortunately, that people’s lives are guaranteed to have the potential to be good and meaningful.” Telling people they can overcome terrible situations, he added, “is a kind of deception that is uncharitable and unempathetic to people. It’s a failure to acknowledge that there are circumstances under which people’s lives are terrible in ways that no change of attitude could possibly compensate for.”

It was hard for me to disagree with Setiya’s last point. It would be absurd to suggest the Cambodian woman who told me about the death of her children might somehow recover from the trauma by reinterpreting the events of her life.

It wasn’t hard for McAdams to disagree with Setiya. “Decades of research and clinical experience show that changing beliefs, stories, and self-understandings do indeed change lives,” McAdams said. “People can become happier by changing their thoughts about life. I mean, this is so fundamentally true that I don’t believe I have to argue it.” That said, he added, “happiness and meaning are not solely the product of beliefs. The real world counts. In fact, one of the great values of life narratives is that they change over time. People change their narrative self-understandings as life evolves. Narratives are not fixed traits. They are dynamic and elastic cognitive structures, showing remarkable flexibility in their integrative power.”

As a journalist, I’ve chosen a life that venerates narratives. They are a central part of the story I tell about myself. And when I think about the inspiring people I’ve met, the transformative power of the hero’s journey rings true. The most important factor setting apart those who recover from life’s trials from those who succumb is the ability to maintain a sense of agency, “to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way,” Frankl wrote. Far from caging us, the stories we tell about ourselves can set us free. ![]()