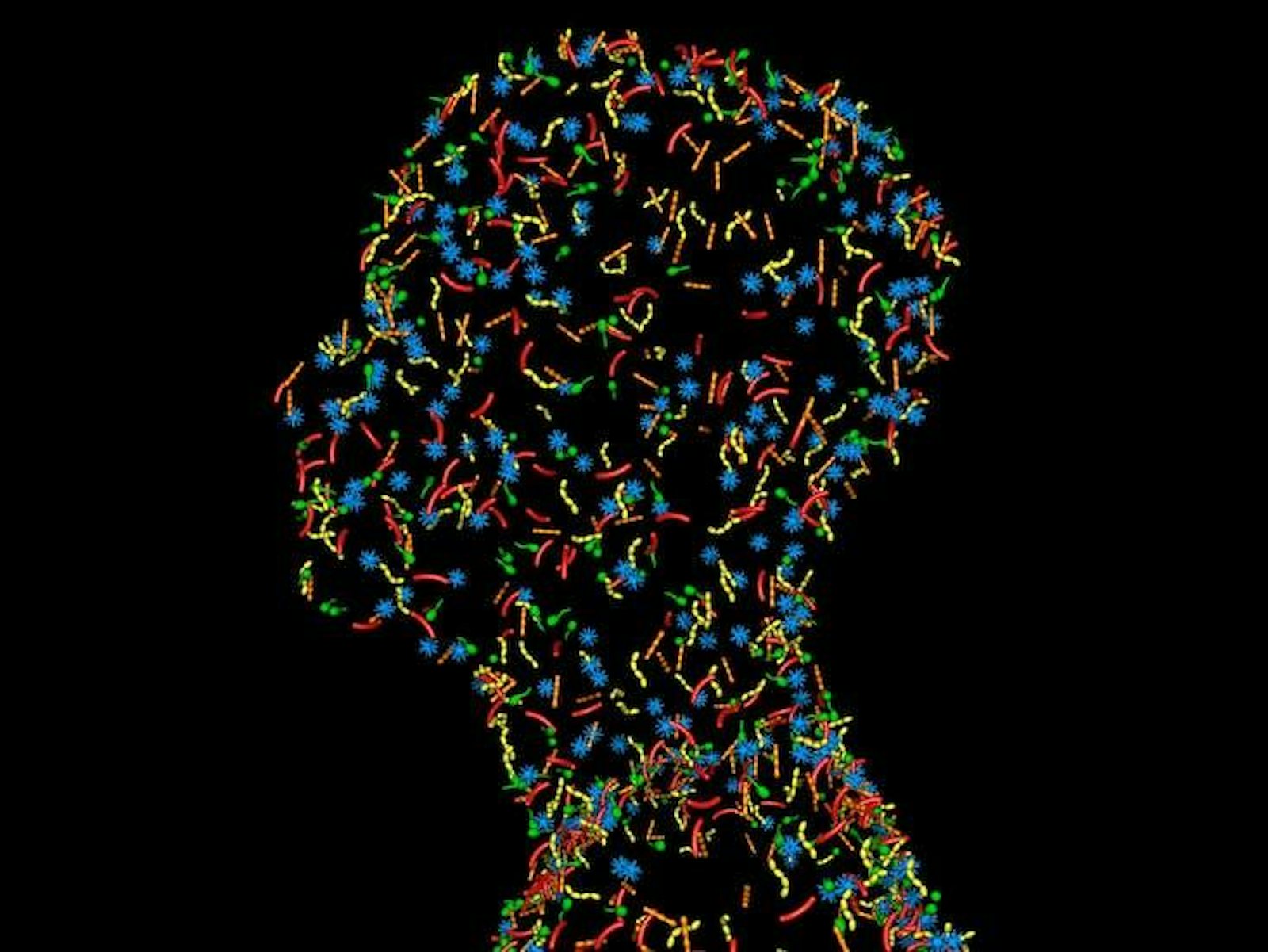

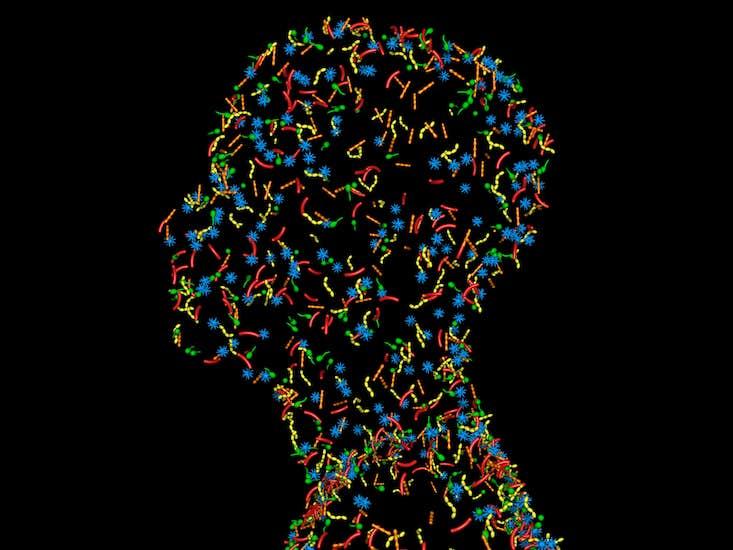

Are you an ecosystem? Your mouth, skin, and gut are home to whole communities of microscopic organisms, whose influence on your body ranges from digesting your food to training your immune system and, possibly, impacting your mood and behavior. What are these tiny tenants, and how do they change the way we think about human health, disease, and even identity?

The human body is made up of trillions of cells—well, trillions of human cells. Around the beginning of the 21st century, scientists learned that in fact the human body contains many trillions more microbial cells—possibly three times as many. This is the microbiome: the collection of microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, and other microbes) living in and on the human body. It is an especially curious discovery—it has been with us, evolving, interacting, and helping to determine our fate as organisms, since before the emergence of the human species itself. And while scientists have known about the existence of some microorganisms on and in the human body since the discovery of E. coli, the magnitude and importance of the microbiome has only recently begun to come to light.

The cells in the microbiome contain as many as 2 million genes—compare that to the approximately 22,333 genes in your own human DNA. The National Institute of Health funds The Human Microbiome Project, whose purpose is to study the various microbial communities in the human body and their roles in human health and disease. We now know that the microbiome contributes a substantial amount to human growth, development, and function. Perhaps the most popular is the gut microbiome, which impacts human digestive health (this is the science behind your daily probiotic yogurt). Aside from digestive health, some scientists are studying the relationship between the composition of the microbiome and the development of the central nervous system, and some psychologists want to take this a step further to investigate the relationship between the microbiome and phenomena like emotion, learning, and social behavior.

But what is the microbiome, exactly? Two biologists, Nicolae Morar and Brendan Bohannan, of the University of Oregon, recently surveyed the metaphors scientists use to talk about the microbiome (an “organ” or a “part of the immune system”) and the human-microbiome complex (a “superorganism,” a “holobiont,” or an “ecosystem”). These metaphors influence scientific understanding and can shape medical treatment. For example, some physicians support fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT); that is, swallowing a pill full of someone else’s poo to treat malfunction of the gut microbiome. FMT follows the same basic principles as an organ transplant, and the treatment is arguably a consequence of viewing the microbiome as an organ.

But this is a limited perspective, because we tend to think of organs as relatively robust to change. Barring significant interruptions, a heart will develop more or less the same in each person and remain the same over time. But the microbiome is shifty, and it responds to tiny changes in our diet, environment, and behavior—like a superorganism. It is “a collection of organisms,” the researchers write, “that interact closely and from which functions emerge that do not exist at the level of individual organisms.” This view is attractive because the human body and its microbiota work to do things that neither could do alone. For example, humans could not get nearly as much energy from digestion without the help of their microbiota, and the microbiota could not survive without a host.

The superorganism view also highlights the history of coevolution between humans and microbiota. Because each needs the other to survive, they evolve in response to one another. But on the other hand, this view tends to minimize focus on the competition that can occur between bacterial populations and a human host.

In general, the problem with each metaphor is that it only captures a part of what the microbiome is and does, and so the researchers conclude that there is no best metaphor, and we need all of them to truly appreciate and understand the complexity of the microbiome and its role in our bodies.

But why might scientists have expected there to be one “best” metaphor for the microbiome? Well, these are not merely metaphors. They are conceptual frameworks, rigorous ways of understanding the microbiome, rooted in its nature. Think about other parts of the human body—your heart, your bones, your blood. Each of these is understood as one thing. An organ, a tissue, a fluid in the circulatory system. Even though each has multiple functions, there is no controversy over whether the heart is an organ or not. So if scientists have discovered something so essential to human health and development that it truly is a part of the human body, it is reasonable to expect that we will be able to think about it the same way we think about other parts of the body.

But the microbiome also seems like a new sort of thing entirely—partially because it really is not one thing. It is trillions and trillions of things, and each of them is an organism on its own. It has many relationships with our bodies, and each is dynamic. What’s more, the microbiome is involved in almost all the bodily structures and processes that we already thought we understood—and so maybe it is not so surprising that there are so many ways to think about the microbiome.

A proponent of scientific perspectivism would say that because scientists put together models and theories of a phenomenon for specific purposes, and because none of those models or theories can capture all of the details of the phenomenon at once, each one is necessarily partial. A pluralist philosopher of science would say we should use all these perspectives to put together theories about the biological world that are patchwork in a way, but all the better for it.

This sounds a lot like the case of the microbiome—but these views are much more far-reaching. Scientists make models and representations of the world when they make their theories, and arguably, the inability to capture everything at once applies in many if not all scientific fields. “We believe that it is time to move beyond metaphors, and we propose a scientifically pluralist approach that focuses on characterizing fundamental biological properties of microbiomes such as heritability, transmission mode, rates of dispersal rates, and strength of local selection,” Morar and Bohannan write. “Such an approach will allow us to break out of the confines of narrow conceptual frameworks, and to guide the exploration of our complexity as chimeric beings.”

The fact that there still isn’t one “best” metaphor for grasping the microbiome might tell us something much deeper about the world—that perhaps the most promising approach to understanding it is to play with a variety of perspectives, prizing none over the others.

Margaret E. Farrell is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science at the University of California, Irvine. Her research is focused on the history and philosophy of biology.