You need it when you drive. You need it when you’re looking for that new shop in the mall. You really need your surgeon to have it when they operate on your kidney. The ability to imagine and manipulate three-dimensional objects in the mind, also known as spatial reasoning, is at the base of many key tasks in our daily lives. But how do we do it?

If you thought it must involve actual images of the objects in your head, you’re in good company. Until recently, the majority of the neuroscience community believed the same. Yet a recent paper by Lachlan Kay, Rebecca Keogh, and Joel Pearson at the University of New South Wales suggests the opposite: Mental pictures are entirely optional—and, in certain cases, they might even be harmful.

Researchers have found deep links between a person’s ability to mentally rotate an object—turn, say, a Z-shaped assembly of blocks around in their minds—and their ability to navigate out in the wild. The same mental rotation skills are also used by chemists to recognize complex chemical structural formulas and by astronauts to control robotic space arms. There is good evidence that one’s skill at mental rotation can predict childhood achievement in mathematics and success in STEM careers. For decades, performance on these mental rotation tests have also been considered a measure of an individual’s ability to call up imagery in the mind.

A good reasoning strategy will often beat the more instinctive approach.

But the discovery of aphantasia complicated our understanding of the relationship between visual imagery, mental rotation, and spatial reasoning, says Kay. In 2015, a group of researchers at the University of Exeter found that between 2 percent and 5 percent of all people have no mental imagery at all.

People with aphantasia have a non-visual imagination. When asked to “picture” a cat sleeping on a sofa, they imagine the abstract concepts “cat” and “sofa,” not an image of the scene. At the same time, they seem capable of conducting perfectly normal lives. It is not surprising, then, that researchers began to wonder how people with aphantasia would fare on standard mental rotation tasks.

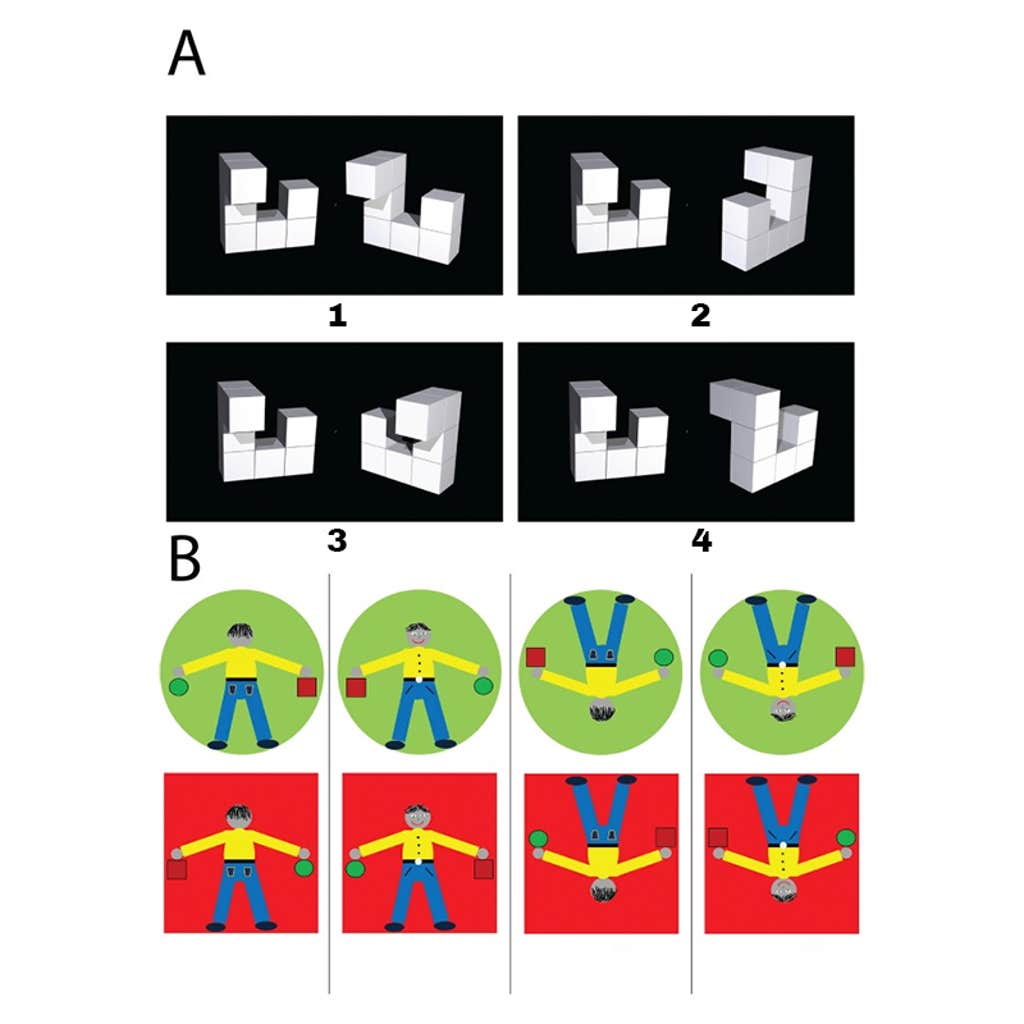

This is the question that Kay and colleagues set out to answer in their latest study, published earlier this year in the peer-reviewed journal Consciousness and Cognition. They recruited people with aphantasia and people with normal visualization abilities and had them perform a series of tasks involving mental rotation. The participants had to compare two images and guess, as quickly as possible, if the images were showing the same object from different angles or not. In one set of tests, the objects to be compared were three-dimensional assemblies of cubes, while in another one they were stick figures with geometrical shapes in their hands.

The results were unexpected. The Australian team found that the aphantasics didn’t simply fare well at the tasks—they did better than the control group on average. They were a little slower, but showed higher accuracy overall, guessing which object pairs were identical more often than the people with standard visualization abilities.

To better understand what was going on, the researchers asked the participants what mental strategies they used to make their judgments. As expected, the visualizers mostly reported rotating the objects in their minds in order to find the answers. Most of those with aphantasia, on the other hand, claimed to be using non-visual “analytic” strategies, like “if the stick figure is turned back to front, its right hand aligns with my right side.” Such logical rules don’t require the manipulation of mental pictures.

Especially interesting was the observation that there were many more cases of people answering quickly and incorrectly in the visualizer group compared to the aphantasia group. The fastest aphantasics were also the most accurate on average.

The reasons for this difference in performance might imply an excessive reliance on visual imagination for those who have it. Previous studies had shown that the time necessary to visually rotate an object in one’s mind is proportional to the angle of rotation. Thus one can be too hasty, attempting to speed up the mental rotation beyond one’s capacity to keep track of the details.

This wouldn’t be the first time scientists find that visual imagination can lead people astray. As early as 1920, American psychologist Cheves Perky famously found that, under certain conditions, visual imagery in a person’s mind can interfere with their perception of real objects. This phenomenon has come to be known as the Perky Effect.

More recent research has shown that visualization can interfere with actual vision if the mental representation of an object or scene is too similar to the real one. These and other studies led the German psychologist Markus Knauff to the more general claim that “visual images are not relevant for reasoning and can even impede the process.” But his ideas have remained on the fringes of academic consensus.

The findings by Kay and his colleagues offer new evidence that mental faculties once believed to be essential for our normal functioning—such as the ability to consciously summon mental pictures—may become a hindrance under certain circumstances. A good reasoning strategy will often beat the more instinctive approach.

Fortunately, evidence suggests that analytical reasoning related to mental rotation and other spatial skills can be taught, increasing one’s performance on intellectual and practical tasks. Anyone, in theory, can learn to reason through our complex three-dimensional world. Surgeons included. ![]()

Answers: A: The figures in 3 and 4 don’t match. B: Left hand in all of them. Illustration from Kay, L., Keogh, R., & Pearson, J. Slower but more accurate mental rotation performance in aphantasia linked to differences in cognitive strategies. Consciousness and Cognition (2024).

Lead image: Eireen.zn / Shutterstock