Imagine that, for once just for kicks, you decided to play the lottery and, not long after, you saw that the winning numbers were yours. You’re now millions of dollars richer. Do you think you’d be happier? Most of us think so. Now imagine that, instead of winning the lottery, you got into an accident and just learned that you’ll be paralyzed from the waist down. That would be a downer, right?

I’d think that, too. But studies of people who have these great and terrible things happen to them follow a curious pattern: Lottery winners are happier and people put in wheelchairs are sadder—but not for very long. After a few months, they return to whatever level of happiness they were at before.

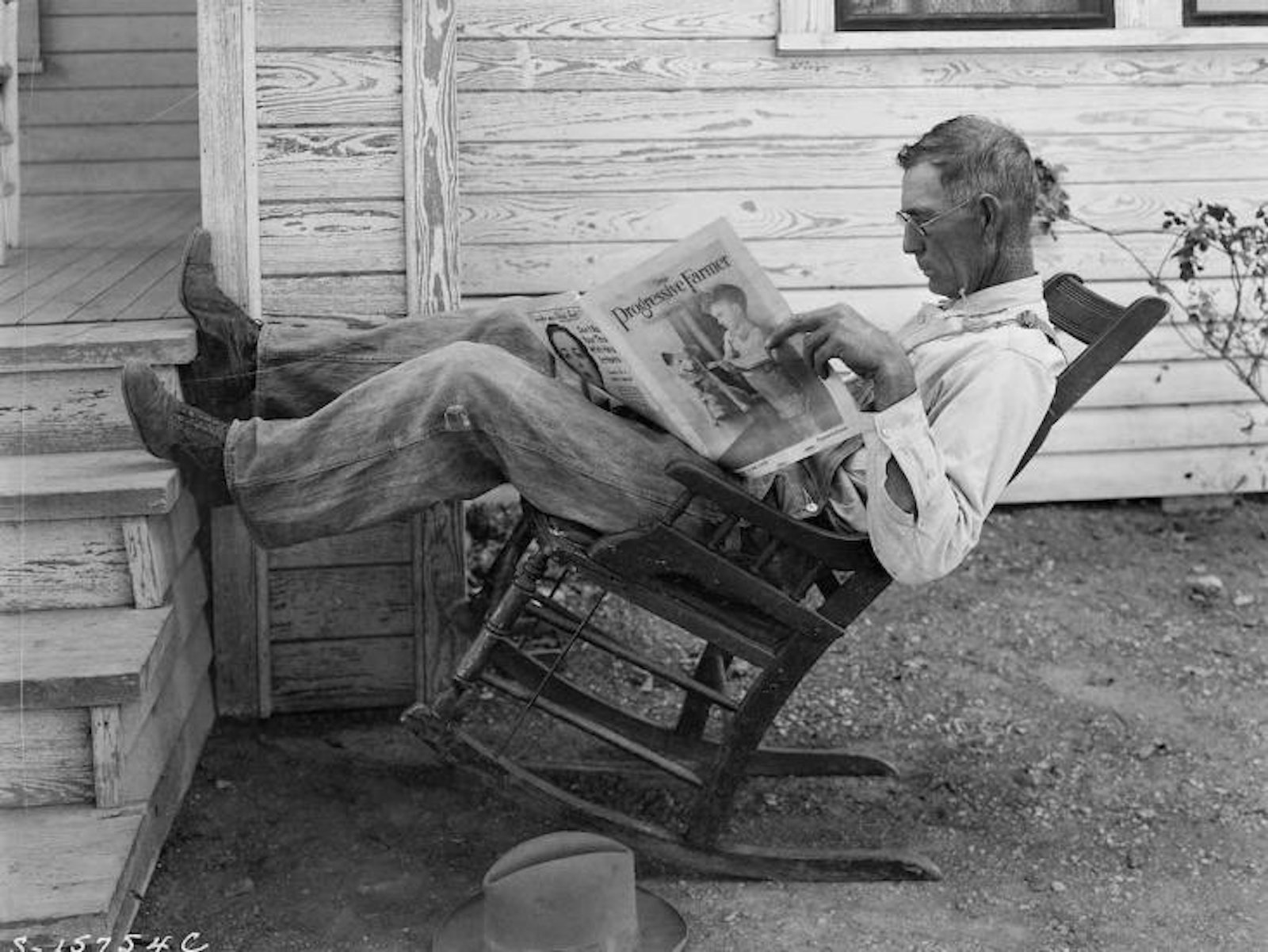

Like a rocking chair that levels out when you get off it, people seem to have a set point of happiness that they return to whatever life throws at them. We all know people who are miserable even though their lives seem just fine, and others whose lives are in ruin but somehow always seem cheerful. The difference in their happiness isn’t due to differences in life-quality, but their different internal happiness set points: A shocking 80 percent of our happiness is, believe it or not, genetic. The reason this seems strange is because we have a cultural myth that says we’re happy or sad because of how well our lives seem to be going. But our minds don’t work like that; instead, they evolved to notice changes, and when something becomes the new normal—like suddenly having millions of dollars—we adjust.

Set points appear at many levels, and our survival usually depends on them not changing too drastically. Our body, for example, has many regulatory systems that work like a thermostat, keeping our bodies in equilibrium. Your brain has to stay near 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit or really, really bad things will start to happen. If it rises only a few degrees, you start convulsing, and a few degrees more and you’re dead. Your body has several strategies for maintaining the optimum temperature: increasing or decreasing blood flow through dilation, decreasing brain activity, or even the outright destruction of nerve cells. We have similar systems at work for pH levels, our endocrine system, and many others.

Happiness and brain temperature seem to have set points, but we also modify our behavior to maintain other set points that we’re not consciously aware of. The historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan, for example, found that homemakers in the 1800s spent the same number of hours doing housework as homemakers in the 1990s. Even with all of the timesaving devices we’ve created since then, like washing machines and vacuum cleaners, people are still spending the same amount of time cleaning. Radio host Claudia Hammond says that there’s no doubt radio editing is faster than a few decades ago, when it was done by cutting and connecting bits of tape. “But now that today’s digital editing means we can edit much faster it has also allowed us to become fussier,” she says, “removing every ‘um’ and ‘er’ and experimenting more with the order of a piece.” She has a higher standard and, as a result, spends the same amount of time editing. Writing and sending emails also takes less time than writing and sending letters through the post. So do we spend less time communicating? No—rather than keeping the number of communications the same and saving time for other, more worthwhile things, we end up sending more email.

There’s also a phenomenon we may call “dietary licensing”—a person who snacks on just doughnuts on one occasion will, on another occasion, eat more doughnuts if they’re paired with a salad.

Interestingly, in these cases, our set point is how much time we believe should be spent on something, not some more objective level of, say, how clean the house should be or the quality of the radio show. We are like a thermostat of time, working more or less to maintain an unconscious set point. It might have been the other way around, with set points relating to quality, but it’s not.

There also seems to be a set point for morality—a point at which we feel that we’re being “good enough” and then stop trying. One study, for example, had a group of people imagine performing some good deed (cleaning a park area of a university). The people who did the imagining were then more likely to cheat on a game that would give them money than a control group, who did not imagine performing a good deed beforehand. This suggests that even thinking about doing something good can get you to let yourself morally off the hook, free to do something bad. What’s more, people who buy “green” products are, everything else being equal, subsequently more likely to cheat and steal. This offsetting of good behavior is known as moral licensing.

There’s also a phenomenon we may call “dietary licensing”—people who take dietary supplements engage in more unhealthy behaviors. The set point for healthy eating also makes people think that calories from good foods somehow subtract calories from the bad. So a person who snacks on just doughnuts on one occasion will, on another occasion, eat more doughnuts if they’re paired with a salad. Eating the salad actually makes you eat more doughnuts, because you feel you are doing something healthy to offset them. (This effect is stronger for people who are trying to lose weight!)

These psychological tendencies have ramifications at the society level. There is wide consensus that reducing our carbon emissions will slow global warming, and many think that if we find more efficient energy sources, it will reduce emissions. But efficiencies in electricity generation and light bulbs have lead people to compensate for those efficiencies by using more artificial light. As prices fell, people spent more energy. This casts doubt on the idea that we can fight carbon emissions with efficiency. It seems that people have some set point of how much money to spend on electricity, and if we make it more efficient, people will just use more.

Though they’re completely unconscious, our struggle to maintain these set points has big ramifications for the health of our bodies, as well as the whole biosphere. At a political level, we might need laws to help us curb these effects; at a personal level, we might need conscious strategies to make sure we don’t undo the good we achieve by unconsciously licensing the bad.

We become hazardous to ourselves, and others, if we don’t.

Jim Davies, the author of Riveted: The Science of Why Jokes Make Us Laugh, Movies Make Us Cry, and Religion Makes Us Feel One with the Universe, is an associate professor at the Institute of Cognitive Science at Carleton University in Ottawa, where he is director of the Science of Imagination Laboratory.