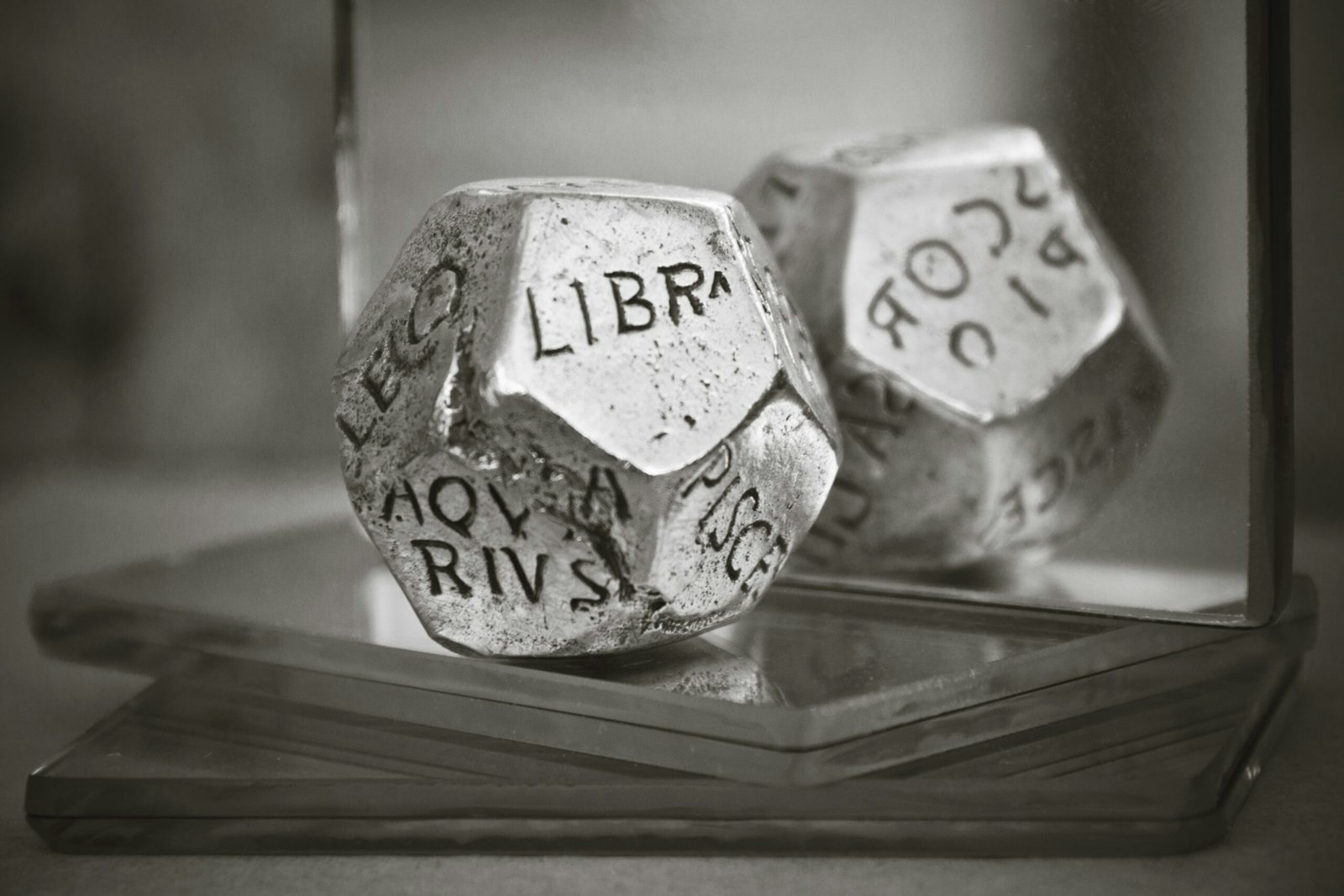

In February, for my birthday, I was gifted a 23andMe genetic test kit. I enjoyed this coincidence: Here was a technology, contra astrology, that would have some real purchase, however limited, on who I am. Holding the small cardboard box containing a tube for my saliva, I considered my sign, Aquarius, which my mother would bring up from time to time to explain or predict my youthful behavior. How remarkable, I thought, that science is fulfilling, in some sense, that ancient aspiration to decipher some measure of our personal nature and fate.

My results weren’t too surprising—no health scares or rude ancestry awakenings—though the report on my muscle composition resonated with me: I’ve got a gene variant common among elite power athletes—sprinters as opposed to endurance runners—who tend to have fast-twitch fibers. Perhaps this explains, by some degree, why I played sprint-heavy sports like football and basketball and hated jogging long-distance.

The geneticist Siddhartha Mukherjee has a metaphor for this: Our genes are lenses through which chance is refracted. Genetics “allows plenty of space for us to interact with environments and with random acts of fate and chance, and thereby, in a kaleidoscopic way, create different outcomes, different cells, different beings, different individuals,” he told Nautilus editor in chief Michael Segal. Take the natural experiment of twins reared in different environments, Mukherjee said. “Two exactly identical genomes superposed on small vagaries of chance and environment yield two very different individual beings.”

This disproves genetic determinism in a strict—but not in a loose—sense. We need no longer speak of destiny as if it were a “gray cloud,” he said. Rather, “we can begin to speak about it—about destiny, about self, about future propensities, however you want to call it—in terms of very incisive information about particular genomes correlating or coexisting with particular environments; and you might find that this end of destiny, this end of the self, has aspects that are strongly genetically determined.”

For Mukherjee, the consequences of understanding the outcomes of particular gene-environment interactions are nothing but life-changing. “The appropriate dissection of these, and the appropriate understanding of the autonomy of each of these interactions allows us, I think, to manipulate human beings and understand human beings to profound effect, and with profoundly dangerous consequences.”

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @brianga11agher.