The season finale of “Rick and Morty,” the Internet Movie Database’s fourth most-popular TV show of all-time, runs tonight. What started as a graphic parody of Back to the Future (minus the headache of time travel) is now a critically acclaimed series with a devoted fan base. It follows a prototypical mad scientist, Rick, and his grandson, Morty, on adventures in alternate universes. David Sims, of The AV Club, summed up the show’s premise as “essentially—what if Doc Brown was a demented drunk? And what if Marty McFly was a lonely kid who got dragged around with him on terrifying and strange adventures through space and time?” The show’s episodes riff on classic sci-fi tropes—from watching interdimensional cable to visiting a miniature theme park inside a human body—and explore profound and wacky what-ifs, as well as more humanistic concerns, like dealing with a divorce or failing high-school.

Nautilus caught up with “Rick and Morty” writer and producer, Mike McMahan, to talk about how science shapes the show.

How does science change us?

One thing we know for sure is that science does not make humans better. It helps us a lot, but science is brand new compared to our evolution. You can have extremely fancy scientific and future-science abilities, but it doesn’t make you a better person. You still have all these human flaws. “Star Trek” used to touch on that all the time. You can travel through dimensions but still get jealous. Stuff can still keep you up at night. You still act like something that evolved to climb out of a tree, to see predators. You can see this a lot with Rick and with Morty, in their adventures.

Was Rick based on any scientist or inventor?

I don’t think so. Dan Harmon, the show’s co-creator, is a genius, and he has this part of him that believes there’s chaos in the universe and that it’s something to be respected. He funneled that into Rick, a fantasy of a human that embodies that, and doesn’t try to control it, but studies it. He’s like an all-scientist, if all scientists were also alcoholic space-magicians.

What makes for good science fiction?

Good science fiction is anything that brings you joy. The concept of hard sci-fi versus other sci-fi is complete bullshit. Every hard sci-fi book that’s good is something that draws you in, has characters that are experiencing things, that are telling it in a human way that makes scientific concepts feel interesting. You could be reading a Vernor Vinge book that’s 3,000 pages long, and it’s about dogs that share a hybrid mind, or you could be reading this new book, A Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet, by Becky Chambers, that has no big sci-fi concepts but aliens chatting and dealing with cultural concepts. What’s important is not the science you choose. It’s the respect you give to the science and to the characters living and dealing with it, having real responses to it.

I have a deep dread about the automated future.

Are there any scientific concepts that you’ve wanted to use but haven’t?

The technological singularity, and: What happens when you can’t tell the difference between robots and people anymore? I’m not sure we’ve hit that much, but I don’t know what our comedy concept of that would be. Maybe Rick used to bang one in college. Or he keyed their car. We haven’t really done too much with AI. We did something with Rick’s car having a great AI in an episode, second season, where Summer gets trapped in the car, but I would really love to go to a planet … “Futurama” did it, though. See, this is the life of “Rick and Morty,” man. Did “Futurama” do it? Did “Robot Chicken” do it?

Are you worried about robots?

I have a deep dread about Moore’s Law, that microchips halve in size every two years, and the automated future. As computers get smarter and we edge closer to the technological singularity, I’m not worried that they’re going to go Terminator on us, but I am worried that we’ve structured our society and our economics in a way that there isn’t going to be any mass market anymore. That’s my existential horror, but other than that, the majority of us are really optimistic on what science and the future say about humanity.

Asimov’s rules for robotics, for society—they’re so clean.

Why do Rick and Morty travel to different dimensions, but not through time?

The complication of story structure when you’re traveling in time, and the logic of how you can affect stuff—those elements have never been something that we’ve had the desire to tackle. When we’re talking about the sci-fi elements and the scientific elements of “Rick and Morty,” we try to get them as plausible as we can, so that after the show’s over you might turn to your buddy and go, “Man, that was a really funny episode,” and then they’re going to say to you, “Well, actually, it was a really good sciencey, scientific episode,” and you’d both be right. The fun of time travel is so great for a drama, but for the storytelling when we’re trying to construct it, it’s just this mountain that we haven’t wanted to climb. In the first season, Harmon was like, “Let’s get to all sorts of different science stories but let’s just not touch time travel,” and Justin Roiland, the show’s co-creator and executive producer, was like, “Yes. Totally agree.”

How did you get interested in science?

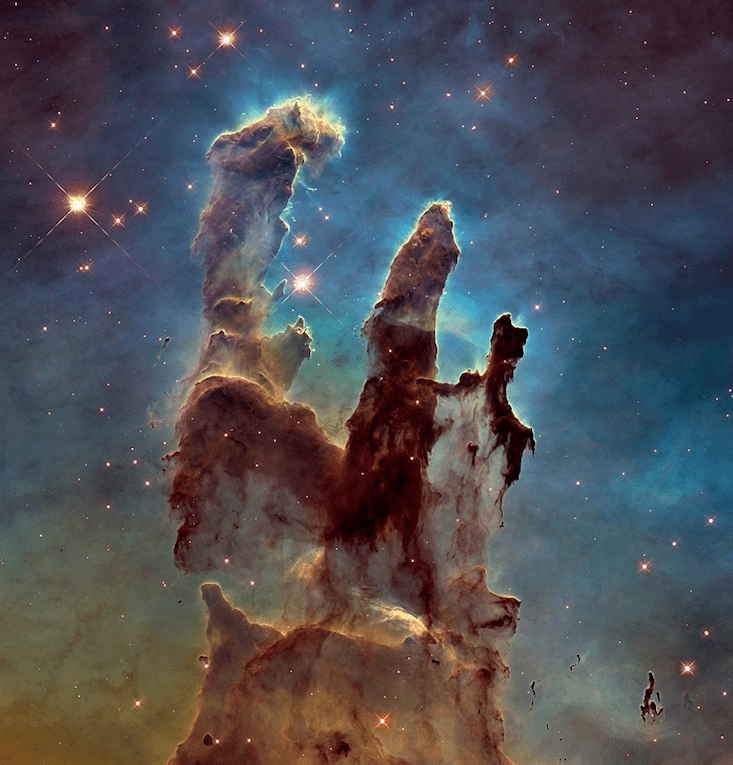

Science was one of the few classes that I really responded to in grade school. You’re learning all the cool, big stuff, about evolution, and we were seeing those Pillars of Creation, that amazing Hubble image.

It was so fascinating, hearing these big, broad ideas. It would be like, “Now we’re going to talk about DNA and Lamarckian genetics.” But when you had to be smarter for it, like, “Now we’re going to use pipettes and study pH balances,” I was like, “Eh, science is getting a little too sciencey for me.”

Why does science fiction appeal to you as a writer?

It’s the escapism of science fiction, having it expand on stuff that we already have and getting to play with it. I love twisting stuff that sounds almost plausible. Star Wars was great, but that’s fantasy to me. It’s fun, but give me a hard science-fiction novel. Give me something that feels like a potential little window. I love the what-if. Just look back at old science fiction and see the stuff that they got right. And I love rules. Asimov’s rules for robotics, for society—they’re so clean. Every day is so emotional, and with sci-fi you get that, but you also get this interesting new set of rules that feels familiar.

Where does science come into the writing process for “Rick and Morty”?

The scientific basis comes in right after we mix an attractive science-fiction concept with what our different, new, funny take on it is. When you get into the process of how it’s scientific, that’s when you start figuring out how you get to play in that world. For instance, we had an episode in the second season called “Total Rickall” that had memory parasites in it. The nascent version of that episode was, “Oh, I love the movie The Thing, and I also love ‘Buffy the Vampire Slayer’ when they add a little sister named Dawn, and they implanted all the main characters memories.” I was like, “What an interesting way to add a character.” If I found out my sister was implanted in my memories, I’d be like, “You’re a fucking villain, whoever did that.” But what would do that? That’s when we started talking about that spore that can get into ants and control their minds to crawl up stalks of grass. That’s the mix of these perfect storytelling things we want to do in a very clear scientific way. Then we can start telling jokes and have everybody running around.

Is there anything you can tell us about the finale?

This finale was so much fun to write. It’s really funny. I don’t want to give you any spoilers. It’s a story we were writing before the series got picked up, when it was still just us writing a couple scripts, before Trump got elected, and it has to do with the president. The president is back. He’s the one from the “Get Schwifty” episode, played by Keith David, who’s amazing. I ran into Keith David at the grocery store the other day, and I was like, “I like you so much more as a president.” That’s all I can say.

Victor Gomes is an editorial intern at Nautilus.

WATCH: The most creative thing a robot has done.