For humans, sleep is an absolute requirement for survival, almost on par with food and water. When we don’t get it, we not only feel terrible, but our cognitive abilities go downhill, and in extreme cases sleeplessness can lead to seizures and contribute to death. And while we share with many other animals this intense commitment to spending much of our lives unconscious, we don’t really know why we do it. A paper published in Science last month suggests that the answer may lie in part with a recently discovered plumbing system that drains waste from the brain. Scientists essentially found that the brain likes to wait till sleep comes before taking out the garbage.

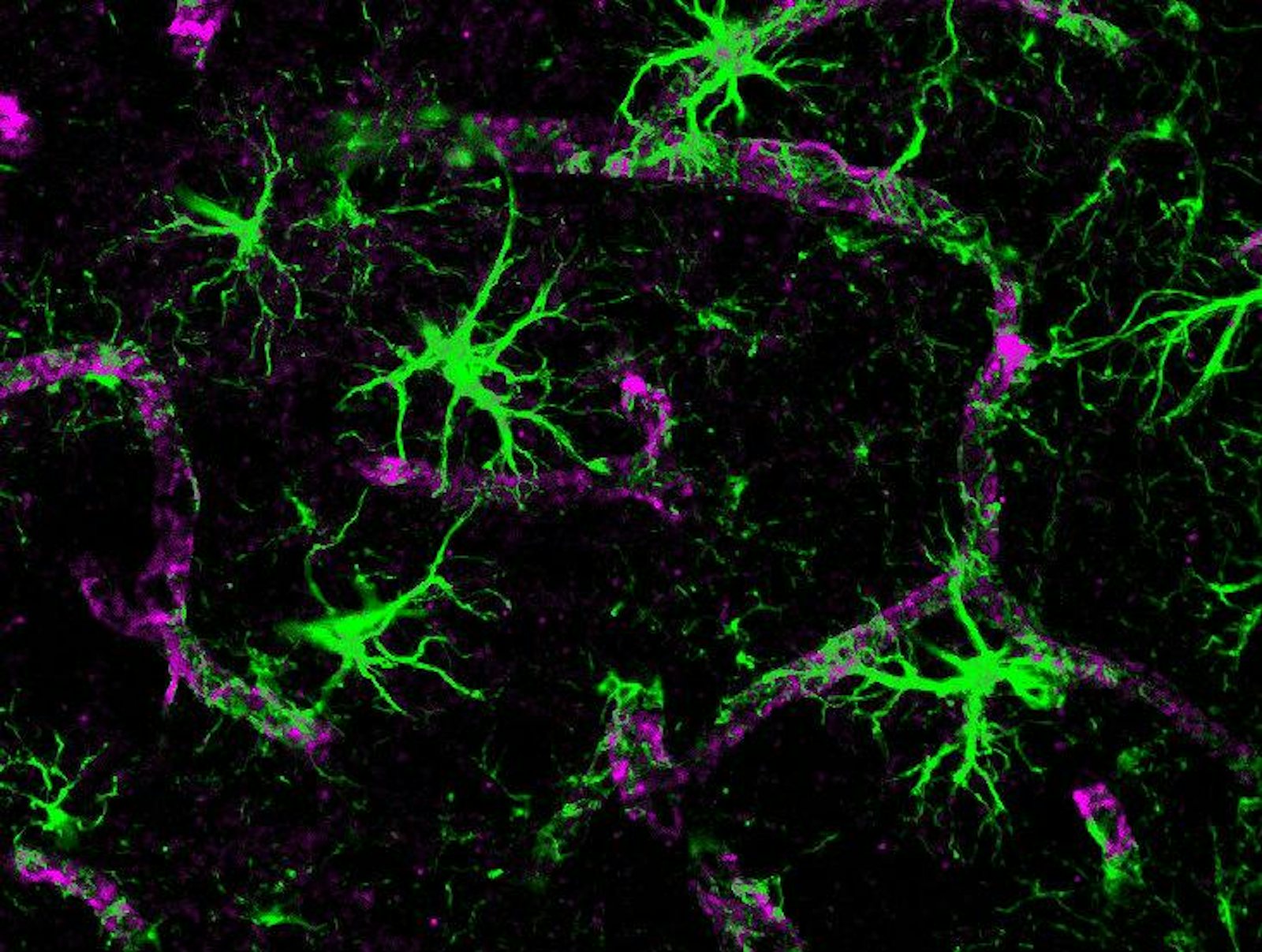

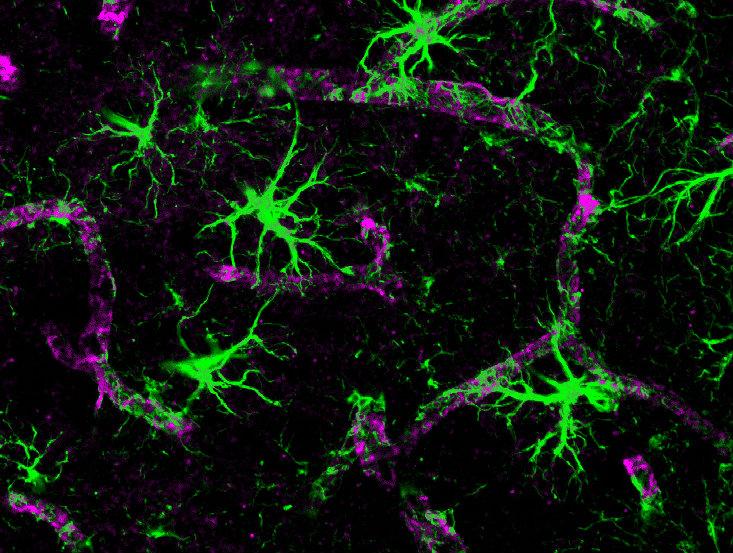

The study follows up on the discovery last year by the same team, based at University of Rochester, that the brain’s waste is removed by a network of channels that run alongside blood vessels. The channels work like the lymphatic system that operates in the rest of the body, collecting and draining what isn’t needed, but they are made of brain cells called glia, instead of the membrane cells that form lymphatic vessels. The channels were effectively invisible to biologists until the development of methods to watch a living brain under the microscope—mouse brains, in these experiments. The discovery of these channels suggested that diseases like Alzheimer’s, in which waste products build up in the brain, might be linked to problems with drainage.

The team wondered whether this system of channels, whose constant pumping action requires a lot of energy, might be responsible for the observation that the sleeping brain uses as much as energy as a wakeful one. To see how the volume of cleaning fluid circulating in the brain changed during sleep, they injected fluorescent molecules into the brains of mice and watched them circulate through waking, sleeping, and anesthetized animals. They even got to see how the flow changed in real-time, as mice emerged from sleep, by gently touching their tails to wake them up.

Remarkably, unconsciousness had a dramatic effect on how much fluid swept through the brain. The sleeping and the anesthetized mice had a 60% increase in the volume of fluid, apparently because brain cells actually shrink to allow more space in the channels. When the researchers woke the mice up, the flow of fluid into the brain abruptly slowed. Further, when the group watched for the removal of beta amyloid, the waste product that gums up the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, they found it left twice as fast in the brains of sleeping mice. The results indicate that the drainage system is particularly active during sleep.

Though things might work differently in human brains, and this waste-management system is not yet well studied, these findings give a tantalizing glimpse of one possible explanation for why sleep is so restorative. Maybe the fresh, new feeling we have when we awake really is a kind of cleanliness, as the byproducts of the previous day’s cogitations have been washed away.

Veronique Greenwood is a former staff writer at DISCOVER magazine. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Popular Science, and the sites of Time, The Atlantic, and The New Yorker. Follow her on Twitter here.