At this stage of the early 21st century, when transparency has evolved from buzzword to business principle, when it’s possible to track anything just about anywhere, you might think it would be a simple matter to choose some everyday product—a cup of coffee, say, or a pen—and trace the paths taken by its parts and ingredients, from raw material extraction to assembly and their final delivery to you.

I thought so, and I was wrong, though instructively so.

Over several weeks, from when my editor at Nautilus commissioned an article for Issue 3, In Transit, to when the article as we’d envisioned it fell apart, I learned that my ideas of globalization belonged to another century.

Sure, I knew that the stuff of our product-saturated world comes from somewhere else, typically not in my own United States. And I knew, though I hadn’t thought much about, how stuff going into the stuff comes from somewhere else, too, that a pair of Nikes made at a Vietnamese factory contains materials from all over the world (1).

But I hadn’t even considered what makes this possible: the inconceivably vast web of supply-chained relationships, intricate as any ecosystem, synchronized like the movements of so many mechanical watches. These supply chains, the ingenuity and industry they embody, are truly marvelous. They’re also quite opaque.

It’s easy to find out how things move—in the air, on the ground, across the seas. It’s far harder, if not downright impossible, to find the source. This is what I learned: At this stage of the early 21st century, we know where everything goes to, but not where it comes from.

After receiving the assignment, I tried to think of common products that would make for a good narrative (2). First to mind was Bit-o-Honey candy, at once folksy and agro-industrial artificial. I imagined buying some at a Brooklyn corner store, finding out who delivered it, figuring out who delivered to them, tracking the shipments back to a single factory and then digging back into the ingredients, finishing in some Iowa cornfield where the “honey” comes from.

Nestlé USA’s brand affairs didn’t want to talk about it, though. Neither was Starbucks inclined to shares the details of their lattés (3), or Kellogg’s their breakfast cereals. In the meantime, I dug into academic literature on supply chains and life-cycle analyses, figuring that someone must have done my work already—a Harvard Business Review case study, maybe, a white paper somewhere on a single well-documented product.

I couldn’t find any, nor could any supply chain experts I contacted think of one. The literature dealt with flows, not sources. It said stuff like, “GSCM is a large mixed-integer linear program that incorporates a global, multi-product bill of materials for supply chains with arbitrary echelon structure and a comprehensive model of integrated global manufacturing and distribution decisions.” I did learn, though, that I didn’t really understand what supply chains are.

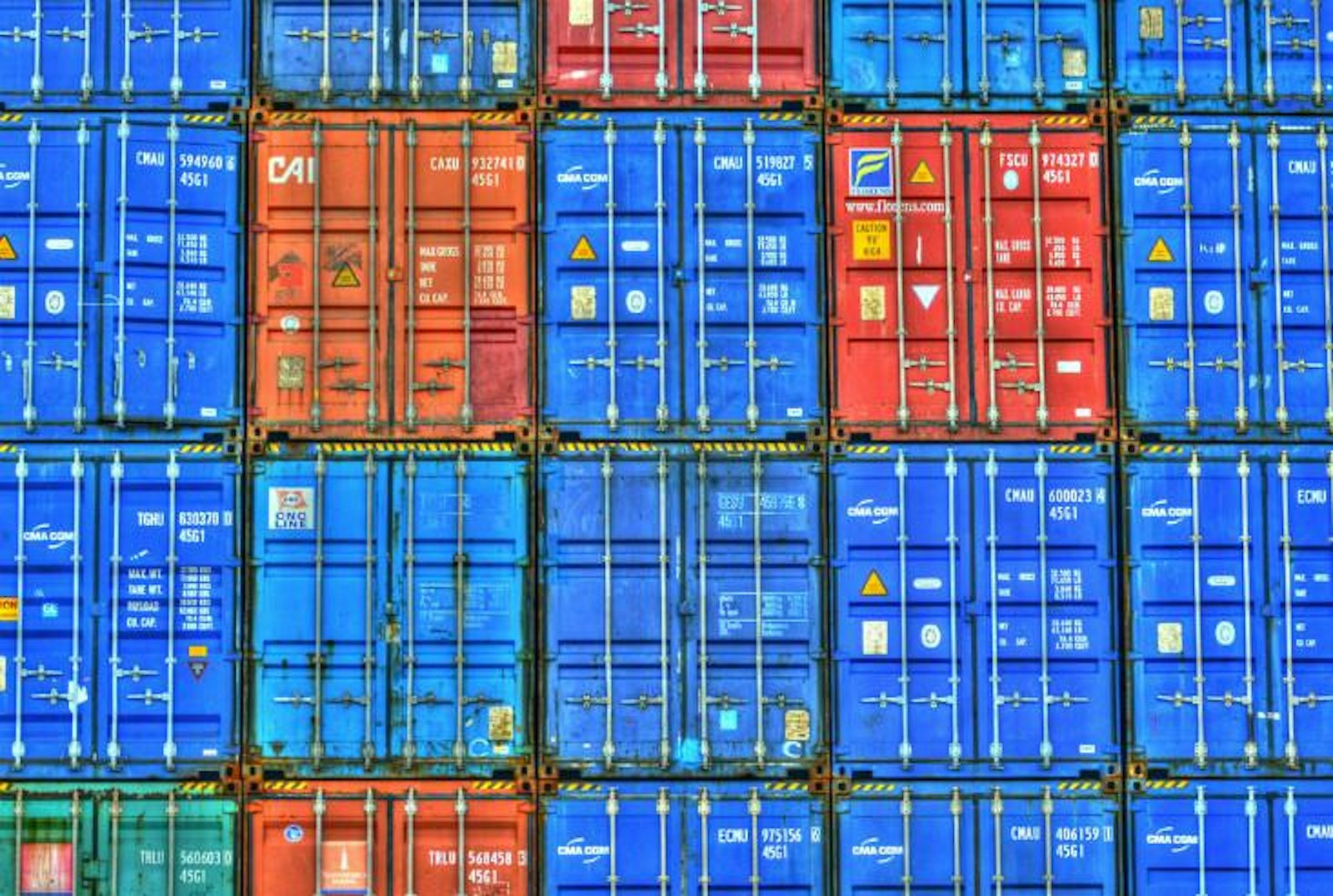

I’d thought of them mostly in terms of delivering Amazon orders and keeping Staples stocked. Those are just endpoints, the final few steps of a waiter carrying a meal on a tray. And what I really didn’t get was that supply chains don’t just carry components and ingredients, but synchronize their movements. Shipping a box of pens to Staples is the obvious part. Coordinating the arrival of barrels, caps, boxes, ink cartridges, and nibs (through which ink flows) at the pen factory—and also metal to the nib factory, oil to the plastics-maker, and so on—is the bulk of what supply chains do, and in the most efficient manner possible, with algorithms optimizing everything from shipping networks to the path of pallets through warehouses, with an eye to what happens when one of these many moving parts goes invariably astray. (See the Nautilus story “The Box That Built the Modern World” to read how containers helped make the modern supply chain possible.)

If you’re a brilliant young mathematician, one of the things you might do, if you don’t feel like theorizing about quantum physics or engineering suspension bridges or figuring out how genomes work, is move boxes. It blew my mind. So did the idea that, from a certain perspective, the actual products almost matter less than the informational structure that guides them.

To some readers, this might be old hat. To me it was like learning of a shadow world. Vivek Sehgal, a product strategist at Manhattan Associates, which counts Wal-Mart and Adidas among its customers, introduced me to an important phrase: logistics cluster. As car manufacturers once gathered in Detroit, or Internet companies in Silicon Valley, logistics—supply chain managers, IT providers, warehouses, shippers and truckers and dispatchers, the myriad businesses that support them—now concentrates in places like Memphis, Tenn.; Zaragoza, Spain; and Rotterdam, Holland, which in a few decades might be considered archetypal 21st century cities, our new Detroits. Sehgal likened them to the Silk Road of antiquity.

Sehgal also shared a Wall Street Journal article on how an unexpected blip in the chip chain ricocheted through a just-in-time-reliant electronics industry in early 2009. In the span of a few months, the industry laid off 20 million factory workers. Economies contorted across Asia.

Perhaps, I thought, I could write about a cell phone or tablet—but no. Kenneth Kraemer and Greg Linden, co-authors of “The Distribution of Value in the Mobile Phone Supply Chain,” disabused me of that notion. It was unrealistic. “Capturing all the logistics linkages for a mobile phone would take years,” said Linden. Even focusing on one part, a single display or chip, would be a daunting: They’re too complicated, and the companies secretive and distant.

Kraemer suggested I try an automobile. That led to a book called Who Really Made Your Car?, almost certainly the most comprehensive effort yet made to answer that question. In it was a graphic of a Toyota Camry with a few dozen parts labeled. Rearview mirror by Magna Donnelly. Aairbag by Autoliv. Pistons from Mahle, a wire harness from Yazaki, the steering column from NSK.

And so I dived into the world of modern automobile manufacture—and, again, I hadn’t really understood it. My mental picture of a car derived from a mid-20th century Detroit factory: a few big buildings, an assembly line, components being assembled on-site, updated with engine blocks arriving from Mexico or somewhere. That bears the relationship to reality as, say, a Bell System rotary handset to an iPhone.

The Toyota factory where the Camry is made, in Georgetown, Kentucky, is simply a final assembly point for what’s known as Tier I suppliers. They provide the major components and are located within a few hours’ ride of the factory, able to deliver a specified part within hours of its order. At the factory, the the supply chain is managed so as to be optimally efficient while planning at the level of individual cars, each custom-ordered and intended for a particular dealership.

When parts arrive at the factory, they’re stored so that, at the factory’s far end, they’ll literally roll out and onto flatbed train cars in the order they’ll eventually be loaded onto delivery trucks: two blue Camrys for a dealership in, say, Bangor, Maine, followed by a white Camry and a Sierra minivan destined to go up the road in Ellsworth. A few thousand cars each day are made this way, one every minute, with some 1,500 on the line at any given moment.

Even more remarkable than the coordination is that it’s done with variability in mind. “If that dealer wanted to make a change to that vehicle”—a spoiler, or front fog lights or leather upholstery—“who gets affected?” said Ananth Iyer, co-author of Toyota’s Supply Chain Management. “What happens to the order we place with suppliers? When should they deliver it, so that everything comes together?”

That level of planning, explained Roy Vasher, another of the book’s co-authors and the co-architect with Bob Bennet of Toyota’s stateside system, doesn’t just include the local suppliers. It extends to the whole sequence in which parts are ordered, all the way back to Japan, planned a week or a month in advance, even as computer systems track and time-stamp every piece on the line.

This includes a national network of trucks, fleets cycling every few hours through each region’s suppliers and delivering the parts to central distribution hubs, a process managed from an operations center in Kentucky, where giant screens show real-time weather reports, traffic delays, and the locations of every Toyota truck at any given moment.

The assembly line no longer covers a factory floor. It covers the continent. I asked: Could I actually trace where the parts came from, all the way back to their sources? Not likely, said the architects. I posed the question to James Rubenstein, author of Who Made Your Automobile?. He explained that the Camry graphic was essentially advertising: a few Toyota suppliers volunteer their information to industry trade magazines, but these are unusual and mostly include Tier 1 and 2 suppliers, who deal with major components. There are many more tiers, and some 40,000 parts to track in all. I might be able to trace a part or two from Mexico or across an Ontario border crossing, but I’d be scratching a scratch on the surface.

“If you are trying to scientifically identify every supplier to Toyota,” Rubenstein said, “you will find that job impossible.”

And so it went. Grasping at straws, I thought that maybe a pen would do the trick, turning to that old writer’s standby, the Pilot G2 gel rollerball. The gracious people at Pilot told me as much as they could: I can now describe the thinking behind the barrel’s diameter, the consistency of the ink, the ink tube’s grease plug, the magnesium alloy point, all designed down to the nanometer. I learned that the pens are assembled in Japan and arrive on container ships at JaxPort, in Jacksonville, Florida, Pilot’s U.S. headquarters and another of the new transportation hubs, to be assembled there from where they’re trucked west on interstates I-10 and I-75 and north on I-95. But where does the oil in the plastic come from? The pigments in the ink? The magnesium in the point? How do they get to the factory in Japan? Proprietary, all of it.

I made one last shot-in-the-dark call, to David Griswold, president of Sustainable Harvest coffee importers, whom I’d written about a few years ago. They’re a coffee middleman, having established their own supply chain to help long-exploited growers get better deals than they could on commodity markets. Among the buyers is Green Mountain Coffee—and, thanks to Griswold, I can relate that, in a Green Mountain single-serving K-Cup, the beans come from hillsides in Veracruz, Mexico, are shipped green to Kearney, New Jersey, carried by truck to Waterbury, Vermont, then roasted and packed into K-Cups. But where does the plastic in the cups come from, or the label? By what routes are they carried across America? Green Mountain politely declined to say.

I called it quits. Later I did come across a book, Pietra Rivoli’s The Travels of a T-Shirt in the Global Economy, which apparently does accomplish what I’d hoped. Per one Amazon reviewer it involved, “years of international adventure and research.” For a T-shirt (5).

So what is the meaning of all this—the great labor it takes to fully understand a product’s history, the near impossibility of knowing it? An old quotation from speculative fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke comes to mind: Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic. Maybe the same goes for process. Any sufficiently advanced supply chain is indistinguishable from magic.

Certainly there’s something magical about how things come together, criss-crossing the world before emerging, as if from the ether, in our everyday lives. But is the magic good? There’s something unnerving about it. The built environment is ubiquitous; we spill reams of digital ink on design talk, and supply chains influence most economic activity. It seems like we ought to know more of the details. I think of another piece of speculative fiction, Paolo Bacigalupi’s short story “Pump Six,” about urbanites eking out an ignorantly precarious life amidst the barely functioning infrastructure of their ancestors, with no clue how to fix it. It’s not a happy place. I think too of William Gibson’s recent fiction, in which characters can expound upon the cultural signifiers of a pair of blue jeans without sparing a thought for people who made them. I think of insects, or corals, even bacteria, that make complicated structures of which they have no awareness.

Maybe I’m making too much of my reportorial difficulties. But it certainly feels strange that in an age of global commerce, of unprecedented amounts of both data and stuff, we don’t know where it comes from—and it’s very, very hard to find out.

Footnotes:

(1) Or, as it’s phrased by The Economist: “The rise of global supply chains means that intermediate goods cross borders many more times than they did in a world where most stages of production took place within one country.”

(2) It probably wouldn’t have been so difficult to do this sort of analysis of, say, a custom handmade acoustic guitar or a $9 pint of hipster-churned artisanal ice cream, but the point was to find a representative mainstream product to which people could relate.

(3) Perhaps understandably, given how their coffee has been tasting this year. Is it just me or did it become a lot more bitter? I wonder if arabica shortages and rising prices resulting from the coffee rust epidemic hasn’t led Starbucks to use more robusto beans in the mix.

(4) Unlike product manufacturers, supply chain people turned out to be quite approachable, perhaps because their feats, so fundamental to modern business, aren’t always appreciated as such, at least by people outside the business world.

(5) Also of interest: the grisly, life-of-a-bullet opening sequence to the film Lord of War.

Brandon Keim (@9brandon) is a freelance journalist specializing in science, environment, and culture. Based in Brooklyn and Bangor, Maine, he often carries sidewalk caterpillars to safety.