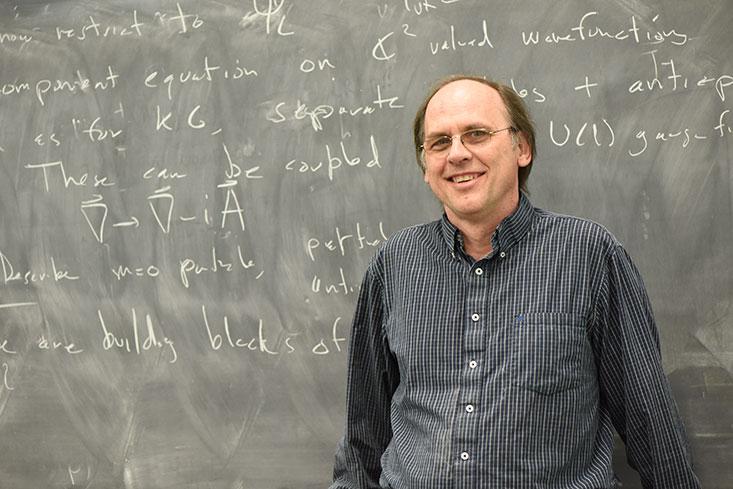

Watching Peter Woit lecture on quantum mechanics to a class at Columbia University—speaking softly, tapping out equations on a blackboard—it’s hard to imagine why a Harvard physicist once publicly compared him to a terrorist and called for his death.

“I was worried,” said Woit’s longtime girlfriend, Pamela Cruz. “Sleep was lost.”

Woit’s crime? A blog and a book, both called Not Even Wrong after a famous barb first wielded by physicist Wolfgang Pauli. Woit uses it against string theory, that most famous contender for the holy grail of physics: a “Theory of Everything” that would unite the two theories that physicists currently need to describe the universe.

The first of these is quantum field theory, which covers the subatomic domain, the behavior of elementary particles, and three of the four forces of nature. The second is Einstein’s general relativity, which explains the fourth force, gravity, relevant only at much larger scales. Unhappily for physicists, these two theories are logically and mathematically incompatible. String theory proposes to solve this problem by replacing elementary particles with strings as nature’s most fundamental objects.

Woit doesn’t buy it.

“This is just getting more and more outrageous, this is just getting ridiculous,” Woit remembers thinking about string theory in 2004, when he started the blog. “There’s this huge public promotion of the theory and there’s all this stuff about how wonderful string theory is …” Woit pauses, shakes his head, and chuckles in disbelief. In 2004 string theory had been a hot research topic for 20 years and “it really wasn’t working.”

He is called an “incompetent, power-thirsty … moron” and a “stuttering crackpot-in-chief” guilty of crimes as contemptible as those of Osama bin Laden.

Woit’s major complaint about the theory, then and now, is that it fails to make testable predictions, so it can’t be checked for errors—in other words, that it’s “not even wrong.” Contrast this with general relativity, for example, which enabled Einstein to predict, among other things, the degree to which a star’s light is deflected as it passes the sun. Had measurements of this effect not agreed with Einstein’s prediction, general relativity would have been disproved. Such falsifiability is a widely cited criterion for what constitutes science, a perspective usually attributed to philosopher Karl Popper. Plus, general relativity took Einstein only 10 years. String theory has taken more than 30 so far.

Woit’s secondary grievance is aesthetic. He, like many physicists, perceives an intricate beauty in the math underlying successful physical theories like Einstein’s. In contrast, Woit says, string theory’s math is “a gory mess.”

So his blog routinely condemns the theory as a “failure, ” and decries the “faddishness,” “mania,” and “arrogance” of physicists who promote its promise. He has publicly urged agencies like the National Science Foundation to cut string theory funding. The reaction from the community is plainly evident online, where he is called an “incompetent, power-thirsty … moron” and a “stuttering crackpot-in-chief” guilty of crimes as contemptible as those of Osama bin Laden.

In his cramped Columbia office, where every inch of wall is covered by books and every surface is stacked with papers, Woit jumps from his chair, swipes the papers off a table, and scrambles on top of it to pull his copy of Introduction to Stellar Atmospheres and Interiors from a shelf. He flips through the pages to find the actual equations that drew him in to physics. “It’s that there’s some kind of almost completely alien and mystical deep understanding of the world that these people are getting,” he says. “But it’s actually very precise and testable and actually is real.”

In high school in Darien, Connecticut, he used a backyard telescope to stare at the stars and was turned on to physics by that exact volume, and other books like it. “I really got fascinated trying to learn about these stars,” he recalls. “There are these mysterious equations that tell you how a star works.”

He’d always been an excellent student. His father was a Harvard-trained lawyer; his mother painted abstract art. Encouraged by his parents, Woit earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in physics at Harvard University and a doctorate at Princeton University. But while doing a postdoc at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, he veered off the conventional physics track.

He’d arrived in 1984, the beginning of what physicists now call the “first string revolution”: a series of mathematical breakthroughs that converted many physicists to a belief in string theory’s potential to be the be-all and end-all of physics theories. A massive migration of researchers to projects aimed at fleshing the theory out ensued.

But Woit, immune to the theory’s charms from the start, refused to follow the crowd and worked on other topics instead. And that made it even more difficult to find a job in an already highly competitive field.

“Nobody was going to hire you,” he says, “on the mathematical end of physics other than doing string theory at that point.” But it seemed “kind of pointless,” he says, “to go and work on something you don’t really believe in.” Woit laughs an incredulous laugh. “Why be in this business? Why not go into another business?”

The “string wars” are an odd mix of impassioned intellectual jousting and playground-worthy name-calling.

He switched from physics to mathematics, working his way up from an unpaid position at Harvard to calculus instructor at Tufts University to, now, a senior lecturer in the Columbia math department, a permanent but non-tenured post. He also maintains the department’s computers.

He says he’s happy with the way things worked out.

“Actually, I found the atmosphere among mathematicians a lot more pleasant than with physicists,” he says. “Physicists tend to be much more competitive.” Many colleagues in physics, he recalls, strove to emulate Murray Gell-Mann and Richard Feynman, two famously acerbic Nobel Laureates prone to one-upmanship. “Those guys were entertaining, but not nice people.” Mathematicians, Woit says, are far more modest. “They understand what they do and don’t know.”

Professor Henry Pinkham, chairman of Columbia’s math department, hired Woit in 1989 and admires him for being the “intellectual equal” of the department’s tenured faculty, yet showing no resentment at being on call for their computer support. He’s also impressed by Woit’s chutzpah, given the presence of tenured faculty who work on string theory in the department. After Woit’s book, “I was expecting fights in the lounge,” he joked.

While nothing happened in the lounge per se, there were certainly fights. Within a few months of Woit’s book being published in 2006, physicist Lee Smolin published The Trouble with Physics, expressing a similar skepticism. Woit and Smolin became string theory’s two most famous (or, to string theorists, infamous) gadflies.

They also provoked what became known in physics as the “string wars,” an odd mix of impassioned intellectual jousting and playground-worthy name-calling in magazines, panel debates and, of course, online. The professor who compared Woit to bin Laden was uniquely reckless and has since left Harvard, but even far less mercurial people were peeved.

“I read the books and was a little exercised by them at the time,” is how Michael Dine, a professor of physics at the University of California at Santa Cruz, and a major contributor to string theory, puts it.

Others were more lighthearted. “I, like many others, followed it like a tabloid. It was a physics version of Big Brother or the Kardashians,” says Abhishek Agarwal, a physicist who’s worked on string theory and who is now an editor for the journal Physical Review Letters, one of the field’s most prestigious publications. (Agarwal emphasized that his remarks represent his personal perspective as a physicist, not as the editor of Physical Review Letters.)

It’s a mistake for anyone to try and dictate what physicists should and shouldn’t explore.

The greatest vitriol was reserved for online interactions, as you might expect. His rivals would pounce on something he wrote, says Woit, “take it out of context, and then [say] ‘Oh now I can show that Peter Woit is a fool and doesn’t understand what he’s talking about.’ ” He marvels at this treatment from “some of the smartest people in the world.” The fighting reached into professional forums, too. Woit had sometimes posted links to his blog entries on the website arXiv.org (pronounced “archive”), a repository for physics papers awaiting peer review run by Cornell University. But during the string wars, Woit says, his ability to post links on arXiv was revoked. “That whole story is one of the most disgraceful, intellectually dishonest pieces of behavior I’ve seen,” he says.

One wonders, too, about hallway encounters between Woit and Brian Greene, the Columbia physicist who is probably the country’s most famous string theorist and who has an office one floor above Woit’s. Greene writes popular books and appears regularly on TV. During the string wars, Greene wrote a soaring New York Times op-ed in support of the theory. Today, a link to the article on Woit’s Columbia website is labeled “The Empire Strikes Back.”

Greene and Woit are not just opposites in their academic ideas. A 24-year-old Columbia physics major named Seth Olsen, who has taken classes from Woit, calls Woit a great teacher but also “a strange bird.” Brian Greene, he says, is different: “Someone like Brian Greene, when you talk to him you feel like you’re almost being seduced or something, like he’s got this motive, he’s crafted this persona, and it’s smooth. But with Woit it’s like you’re looking into the guy’s soul. He’s, like, shaking a lot of the time, thinking out loud, sometimes muttering.” Some peers, Olsen says, think of Woit as “Brian Greene’s archnemesis.”

The string wars have proven to be so intractable in part because even the experts aren’t always on the same page about string theory’s testability. String theorist Matthew Kleban of New York University believes that a particle accelerator running at high enough energies (far beyond the reach of current technology) could, in principle, prove whether strings exist or are figments of physicists’ imaginations.

“Strings have resonances,” he says, “like a guitar string. So there’s a pretty specific prediction for how they’ll behave once you start being able to excite those resonances. That would be a very sharp and specific prediction that could be tested.”

But Santa Cruz’s Dine is not so sure, pointing out that, “If you ask different string theorists what string theory is, you’ll get different answers.” String theory, unlike Einstein’s relativity, is not a specific set of equations, but rather a framework, or a class of equations of a particular style. As far as its testability goes, Dine says, “It’s not exactly clear what the question means. It’s just not something we can formulate well.”

For Agarwal, string theory’s testability is not necessarily the most relevant question. He points out that a mathematical correspondence discovered by physicist Juan Maldacena in 1997 implies that string theory has deep mathematical connections to quantum field theory, and therefore to well established, and tested, physics. Called the “AdS-CFT correspondence,” it allows physicists to use string theory as a lens on more universally accepted physics. Woit, Agarwal says, “doesn’t give enough credit to a whole bunch of interesting things about quantum field theories that we’ve learned from string theory.”

Agarwal adds that most string theory research being done today is motivated by the AdS-CFT correspondence, and not by Theory of Everything dreams. And that the AdS-CFT discovery illustrates why it’s a mistake for anyone to try and dictate what physicists should and shouldn’t explore. “You cannot plan development in science that way. You just can’t,” he says. “Just imagine if one had cut off string theory funding in the mid-90s. Well, that would not have made AdS-CFT happen. My impression from Peter’s blog is that even he regards AdS-CFT and related developments very well since they connect to subjects that he is interested in.”

Today, the string wars have settled down to “string skirmishes.” Woit’s blog continues to be widely read by physicists and mathematicians—and to be a lightning rod for debate. Woit’s suspension from the arXiv sparked a battle of words there just this past December, between Woit and the prominent string theorist Joseph Polchinski of the University of California at Santa Barbara. The two went blow for blow, Polchinski taking Woit to task for “charged words,” and Woit upping the ante by calling Polchinski “sleazy and unprofessional.” Their posts continued through Christmas Eve.

But the string wars have left the tranquility of Columbia University’s hallways undisturbed. Looking relaxed with his hands behind his head at his desk, Woit says that his relationship with Greene, for example, has always been amicable. “Brian joked that he’d give me a cut of his increased book sales,” he says, flashing a crooked smile.

Bob Henderson studied physics, worked on Wall Street, and is now an independent writer focused on science and finance.

Lead photo by Shutterstock.