Last fall, the United States government bought lunch for some hungry schoolchildren in Mozambique. Though the students lived in their country’s best farming region, where deep green hills cover rich, red soil, their benefactors didn’t buy the food nearby—nor even from their wealthier neighbors in South Africa. Nor did they turn to the children’s farmer parents to grow their own. Instead they followed a culinary tradition any American can relate to: They had it delivered.

On the surface, that type of giving makes sense. The U.S. is not only one of the richest countries on the planet, but also a preeminent food producer. Even as the U.S. has shipped scores of non-farm jobs overseas, it continues to enjoy a $32.4 billion agricultural trade surplus. A recent study in the journal Food Policy estimated that the amount of food Americans throw away without eating totals more than $165 billion every year—equal to one-seventh of the combined economies of all 48 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

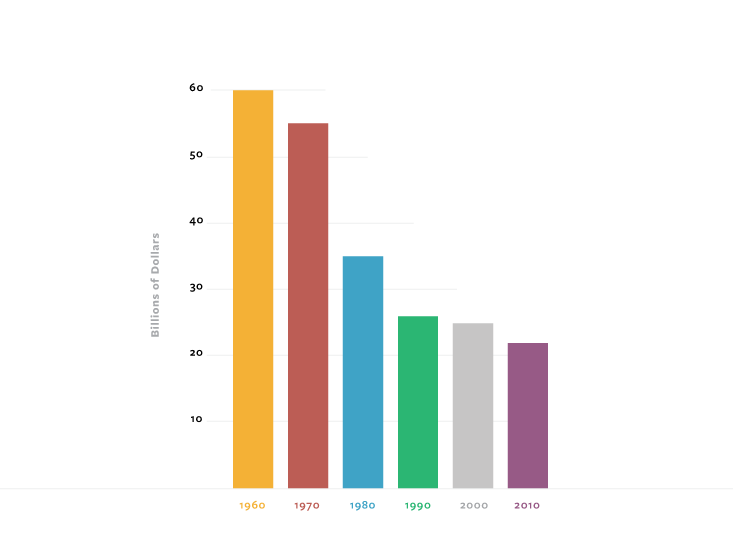

So, for the past 60 years, we have followed that logic to its apparent conclusion: relying on transportation to get food from the bountiful U.S. to countries where hunger is widespread. Those food giveaway programs, organized primarily under the U.S. government’s “Food for Peace” initiative, have developed into a $1.4 billion-a-year industry.

Yet something is clearly not working. Take Mozambique. Through 2012, the East African nation was one of the top ten recipients of American food aid. Three years ago, the U.S. spent $25.9 million shipping U.S. produced commodities across the Atlantic, around the Cape of Good Hope, and up the coast of the Indian Ocean, bound for Mozambican villages, towns, and schools. Yet for all that giving, Mozambique has not been better off. A quarter of its 24.1 million people face acute annual food shortages, according to the United Nations World Food Programme. More than 1.7 million of its children under 5 years of age suffer chronic malnutrition.

How can so many millions of dollars fail to buy food security for people in need? The answer is in the journey itself.

The amount of food Americans throw away without eating totals more than $165 billion every year—equal to one-seventh of the combined economies of all 48 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.

In October 2012, nongovernmental organization World Vision U.S., based outside of Seattle, asked the U.S. government for a thousand metric tons of “corn-soy blend” to use in its school feeding programs in Mozambique’s northern Nampula Province. Corn-soy blend is a vitamin-fortified cornmeal and soy flour mix that can be cooked into porridge, fritters, or pancakes. It’s a favorite product of U.S. farmers because they can produce corn, in particular, more efficiently than their foreign competition—thanks in no small part to the billions of dollars in government subsidies they receive each year. Corn-soy blend has thus become a staple of food aid programs around the world.

When it received the order, the U.S. Department of Agriculture put out a call for bids. Anyone could apply, but large agribusinesses typically offer the most competitive rates. For the Mozambique order, the winning bid came from private, family-owned Didion Inc. of Wisconsin—the fifth-largest supplier of U.S. food aid, according to a 2012 investigation by The Guardian. Their asking price: around $850,000.

In January 2013, the order was loaded onto trucks and trains, bound for the international seaport in Houston, where another bid winner waited: a hulking single-engine diesel ship, with a dusky black hull, rust-covered cranes, and a towering white bridge, called the Noble Star.

The ship’s owner, New York shipping firm Sealift Inc., asked for $431 per metric ton for the 8,500-mile journey to Africa, then another $300 for shipping overland to World Vision’s warehouse in Mozambique. That brought the total cost of food and delivery to roughly $1.5 million. Just under half the cost was devoted to transportation alone.

But a ship like the Noble Star can’t bring lunch very quickly, at any price. Traveling at roughly 14 knots, a ship such as the 16,000-ton freighter needs “at least a month in good weather for the trip from Houston to the east coast of Africa,” said Judith Thimke, a shipping expert at the U.N. World Food Programme. If the seas are rough or traffic bad, it can take longer.

Once the Noble Star docked, its load of corn-soy blend needed 15 days to clear customs. Then the food was loaded onto trucks and driven to Nampula Province. The overland part of the trip can be hazardous: Bad roads, floods, communication breakdowns, or even hijackings by bandits have been known to thwart deliveries.

This shipment arrived unscathed. After its long journey, the food was unloaded at World Vision’s warehouses in the villages of Muecate and Nacarôa in March. In May 2013—seven months after the order was placed—it was finally distributed to the schools, where it was used for meals for 56,000 children, according to World Vision.

That’s not a number to sneeze at. Surely the children and their parents appreciated the meal. But once lunch was over, what was left? Most of the money spent on the shipment had never left the U.S. The children and their parents in Mozambique were as poor as ever, left to await the next shipment of food, or food crisis, whichever came first.

Examples like this one have led experts and aid workers to conclude that transporting commodities halfway across the planet is not a solution to global hunger. The problem, says Christopher Barrett, an economist at Cornell University and one of the world’s leading experts on food aid, is that the U.S. has an entirely different goal when it comes to sponsoring humanitarian assistance. Feeding the hungry has never been its sole purpose.

Rather, the historical goal of food aid has been to stimulate U.S. businesses—the agriculture and shipping industries above all. Modern food aid was devised in the early days of the Cold War as a way to dispose of government-held surpluses, in order to regulate crop prices at home and create markets abroad. The main programs in the early days of food aid didn’t even give food away for free, rather selling it to foreign governments at a discount. “It just happened that this could get advertised as and provide humanitarian relief on occasion,” Barrett said.

Over time, things began to change. Surplus disposal became less important than other forms of domestic price control, and the cheaply sold food did not prove very effective in opening markets. When in the 1970s and 1980s, food donated during famine emergencies in Asia and Africa proved effective, free-food distributions took over as the dominant programs.

In May 2013—seven months after the order was placed—it was finally distributed to the schools, where it was used for meals for 56,000 children.

Today, the major players in food aid are nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as World Vision. But, because of how American laws are structured, domestic corporations still reap the much of the profit. Major U.S. agribusinesses can count on hundreds of millions of dollars in annual sales to the government.

Shipping companies do even better. Federal law mandates that at least half of all U.S. food aid must be shipped aboard U.S.-flagged vessels. With shipping costs taking up nearly 40 percent of any food assistance funding, the law guarantees hundreds of millions of dollars in contracts for shipping companies. The winner of the Mozambique shipment was no exception: Sealift Inc. has grossed $203 million in government contracts since 2011, mostly from the Pentagon, according to data at USASpending.gov. This benefit is not lost on the shipping industry: The sector’s leading coalition, USA Maritime, spent $250,000 lobbying Congress on food aid and cargo-preference laws in 2011 and 2012.

The NGOs profit as well. Some, including World Vision, monetize a portion of the aid they are given to local markets and use the proceeds to finance their programs. A 2011 Government Accountability Office report found that this process, known as “monetization,” had squandered $219 million in aid money over three years.

Little of that benefits the people whom food aid is supposed to help. In fact, it can harm. That’s because, contrary to popular belief, even in most countries where there are chronic food crises, there is usually enough food to eat, if only people could afford it. “The issue isn’t availability. In most markets, the issue is affordability,” explained Oxfam’s Eric Muñoz. Dumped heedlessly, donated food can undercut local farmers or cause prices to swing wildly. In the end, poverty can get even worse.

The way to make aid programs more effective isn’t to find a faster, cheaper ship, experts say. It’s to change the way that aid works entirely.

One answer that social scientists have come up with is local procurement. Recent studies of a USDA pilot program found that buying food closer to the place where it is going to be distributed is generally cheaper than long-distance imports. The studies also found that recipients, perhaps unsurprisingly, tend to prefer the taste of local products as well. Supporters of food-aid reform say that allowing increased local procurement could feed an extra two to four million people a year while putting money directly into local markets and helping to develop economies.

Economists and social scientists don’t think that reform efforts should stop there. A growing research consensus has shown that another effective form of aid includes giving people vouchers to buy food in their own markets, or even just handing out cash so they can decide how to use it themselves. A special June series in The Lancet journal focused on studies and articles on combating malnutrition in the developing world. Editors explained that such investments can “increase producer incomes while protecting consumers from high food prices.”

When food aid is used, experts from a variety of backgrounds argue that it has to be targeted well. One of The Lancet’s articles argued that scaling up ten highly-targeted nutritional interventions for the neediest pregnant women, newborns, and young children in the world’s poorest countries by about $9.6 billion annually could save nearly a million children’s lives per year. Another study, from the Stanford Business School, advocated screening children by height and weight to determine which are the most vulnerable and then concentrating resources on those most at risk—a strategy the authors said could reduce current costs by 61 percent while providing the same amount of health benefits.

Contrary to popular belief, even in most countries where there are chronic food crises, there is usually enough food to eat, if only people could afford it.

Nearly all the current research advocates following up with recipients of food aid to gauge efficacy and set quantifiable goals for the future. These data-based approaches show that delivering help demands flexibility in the face of changing information. And indeed, flexibility has become the byword for nearly all the major aid-giving countries in the world, including European powers and Canada. Local procurement, voucher programs, and investment in local agriculture have become increasingly larger pieces of the pie.

The lone holdout is the U.S. The Obama administration announced in April 2013 a plan to overhaul the food aid program. Many experts felt the proposed changes were exceedingly modest: Obama asked to reallocate much of the $1.4 billion budget between programs administered by both the Agriculture and the State departments, where it could be used on vouchers, local procurement, or aboard U.S. ships as needed. In a nod to domestic interests, the administration proposal agreed to keep 55 percent of the current program unchanged, still funding American farmers and shippers. As the Brookings Institution’s George Ingram asked, “How can Democrats and Republicans not be united on a proposal that saves lives and, at the same time, saves dollars?”

Very easily, it turned out. Although food aid makes up less than 1 percent of what American farmers export, their representatives in Congress guard these subsidies jealously. Even before the administration could officially announce its plan, The New York Times reported that 21 senators from farm states—under pressure from lobbyists—had signed a letter asking that the programs be left unchanged. Bills supporting the reform effort were defeated in both chambers of Congress in June, while a farm bill cutting subsidies for U.S. farmers died in the House.

Yet even as supporters of the reform effort vow to fight on in Washington, peasant advocates in developing countries are trying to take the lead themselves. Citing the research pioneered by Nobel Prize winner Amartya Sen in the 1960s that showed smaller farms produce proportionally larger yields, they argue that the ultimate answer to hunger lies in supporting local smallholder agriculture. One such program is the Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Programme, which aims to increase investment in farms to 10 percent of African Union members’ national budgets, with hopes of raising agricultural productivity by 6 percent in the next two years.

Organizers hope that a serious dose of investment will help break the cycles of poverty and hunger, and attract more investment from the outside. Because whether you live in Wisconsin or Nampula, the surest way to get food from the farm to your lunch table is to grow your own.

Jonathan M. Katz, a former Associated Press correspondent, was the 2010 recipient of the Medill Medal for Courage in Journalism. In 2012 he won the J. Anthony Lukas Work-in-Progress Award for The Big Truck That Went By, his book about the earthquake in Haiti. He lives in Durham, North Carolina.