Trust used to be a very personal thing: You went on the recommendations of your friends or friends of friends. By finding ways to extend that circle of trust exponentially, technology is expanding markets and possibilities. Consider the darknet. It is creating trust between the unlikeliest of characters, despite a heavy cloak of anonymity.

You can’t get to the darknet using your regular web browser; most access it via an anonymizing software called Tor (an acronym for “The Onion Router”). The darknet is peopled by journalists and human rights organizations that need to mask their browsing activity but it’s also home to hundreds of thousands of drug sellers and buyers. People who would commonly be stereotyped as untrustworthy, the worst of the worst, yet here they are creating highly efficient markets. Effectively, they are creating trust in a zero-trust environment. Nobody meets in person. There are obviously no legal regulations governing the exchanges. It looks like a place where buyers could get ripped off. Theoretically, it would be easy for dealers to send lower quality drugs or not deliver the goods at all. Yet this rarely happens on the darknet and, overall, you’re more likely to find buyers singing hymns of praise about the quality of the drugs and reliability of the service. Before the FBI shut down the notorious illicit drug site Silk Road in 2013, it testified that more than 100 purchases of drugs they made online all showed “high purity levels.”

It seems dealers are more honest online. And that tells us something about how people create trust in this criminal ecosystem, with the help—or supervision—technology can provide. Given the nature of its wares, the darknet may seem like an alien and subterranean world—and some of it undoubtedly is—but at its core, it’s about people connecting with other people. It’s just another incarnation of the new kind of trust-building that technology has facilitated. The same dynamics, the same principles in building digital human relationships, apply. In that sense, it’s almost comically conventional.

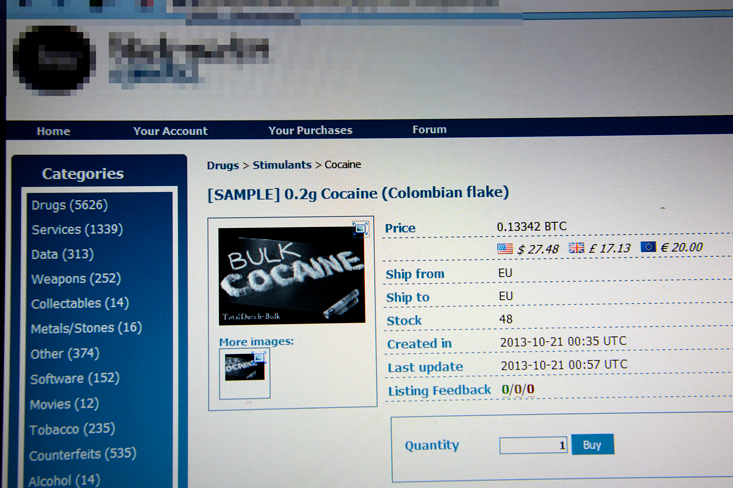

Drug dealers care about their online brand and reputation and customer satisfaction as much as Airbnb hosts or eBay sellers. A typical vendor’s page will be littered with information, including: how many transactions they have completed; when the vendor registered; when the vendor last logged in; and their all-important pseudonym. It will also feature a short description about why a user should buy drugs from them, refund policy information, postage options and “stealth” methods (measures used to conceal drugs in the post). Even if you’re not in the market for what they’re selling, it’s hard not to be impressed; vendors put in real effort to demonstrate their trustworthiness.

Indeed, marketing strategies used on the darknet look remarkably like standard ones. There are bulk discounts, loyalty programs, two-for-one specials, free extras for loyal customers and even refund guarantees for dissatisfied punters. It’s common to see marketing techniques such as “Limited Stock” or “Offer ends Friday” to help boost sales. While reviewing these deals, I had to remind myself I was looking at an illegal drugs marketplace, not shopping for shoes on Zappos.

Some vendors, eager to build brand, label their drugs as “fair trade” or “organic” to appeal to “ethical” interests. “Conflict-free” sources of supply are also available for the benevolent drug taker. “This is the best opium you will try, by purchasing this you are supporting local farmers in the hills of Guatemala and you are not financing violent drug cartels,” promised a seller on the darknet site Evolution (before it was shut down).

New vendors will offer free samples and price-match guarantees to establish their reputation. Promotional campaigns are rife on April 20, also known as Pot Day, the darknet’s equivalent of Black Friday. (The date of Pot Day comes from the North American slang term for smoking cannabis which is 4/20.) “It’s not anonymity, Bitcoins, or encryption that ensure the future success of darknet markets,” writes Jamie Bartlett, author of The Dark Net. “The real secret of Silk Road is great customer service.”

After a buyer receives their drugs, they are prompted to leave a star rating out of five. Nicolas Christin, an associate research professor at Carnegie Mellon University, analyzed ratings from 184,804 pieces of feedback that were left on Silk Road over the course of an eight-month period. On the site, 97.8 percent of reviews were positive, scoring a four or five. In contrast, only 1.4 percent were negative, rating one or two on the same scale.

Drug dealers care about their online brand and reputation and customer satisfaction as much as Airbnb hosts or eBay sellers.

Some observers suspect the darknet suffers from review inflation. Similar studies have been conducted on conventional marketplace rating systems and found that feedback is also overwhelmingly positive. For instance, on eBay less than 2 percent of all feedback left is negative or neutral. One explanation is that dissatisfied customers are substantially less likely to give feedback. It means the most important information, the negative reputation data, is not being captured.

Social pressure encourages us to leave high scores in public forums. If you have experienced an Uber driver saying at the end of a trip, “You give me five stars, I’ll give you five stars, ” that’s tit for tat or grade inflation in action. I know I’m reluctant to give a driver a rating lower than four stars even if I have sat white-knuckled during the ride as he whizzed through lights and cut corners. Drivers risk being kicked off the Uber platform if their ratings dip below 4.6 and I don’t want to be responsible for them losing, in some instances, their livelihood. Maybe they are just having a bad day. That, and the driver knows where I live. In other words, reviews spring from a complex web of fear and hope. Whether we are using our real name or a pseudonym, we fear retaliation and also hope our niceties will be reciprocated.

There is, however, another way to look at the 97.8 percent of positive reviews on darknet sites. Perhaps they are an accurate reflection of a market functioning remarkably well most of the time, with content customers. Even if review systems are not perfect, and bias is inevitable, it seems that they still do their job as an accountability mechanism of social control. Put simply, they make people behave better.

The three key traits of trustworthiness—competence, reliability, and honesty—also apply to drug vendors. To highlight reliability, many reviews point out the speed of response and delivery. For example, “I ordered 11.30 a.m. yesterday and my package was in my mailbox in literally twenty-five hours. I’ll definitely be back for more in the future,” commented a buyer on Silk Road 2.0. One of the ways skills and knowledge are reviewed is how good a vendor’s “stealth” is, that is, how cleverly they disguise their product so that it doesn’t get detected. “Stealth was so good it almost fooled me,” wrote a satisfied buyer on an MDMA listing on the AlphaBay market. Established vendors are very good at making it look (and smell) like any old regular package. Excessive tape or postage, reused boxes, presence of odor, crappy handwritten addresses, use of a common receiver alias such as “John Smith” and even spelling errors are bad stealth.

There is a clear incentive for vendors to consistently provide the product and service they promise: The dealers with the best reviews rise to the top. No feedback, either negative or positive, can be deleted, so there is a permanent record of how someone has behaved. Past behavior is used to predict future behavior. “The future can therefore cast a shadow back upon the present,” Robert Axelrod wrote in The Evolution of Cooperation. Or to put it another way, vendors have a vested interest in keeping their noses clean right from the word go.

I had to remind myself I was looking at an illegal drugs marketplace, not shopping for shoes on Zappos.

Reputation is trust’s closest sibling; the overall opinion of what people think of you. It’s the opinion others have formed based on past experiences and built up over days, months, sometimes years. In that sense, reputation, good or bad, is a measure of trustworthiness. It helps customers choose between different options and, with luck, make better choices. It encourages sellers to be trustworthy, in order to build that reputation, and it weeds out those who aren’t.

It isn’t quite that simple. Price is also a factor in the value of reputation, and reputation can influence price. Still, I was intrigued by how influential a vendor’s reputation really is on cryptomarkets. So I tracked down a buyer; let’s call him Alex. He describes himself as a “casual drug taker” who likes to smoke a lot of weed and occasionally take ecstasy at the weekend. Toward the end of 2014, Alex switched from buying drugs from a dealer who lived relatively close by, to buying through cryptomarkets. What made him switch? “Rather than buying drugs from a friend of a friend of a guy I met in a bar, I can buy drugs after reading dozens of reviews of their service,” he explains. “I feel confident I am getting exactly what I am paying for.” It echoes what drug surveys indicate: 60 to 65 percent of respondents say that the existence of ratings is the motivation for using darknet marketplaces.

An upstanding community may not be something we associate with the drug trade but darknet markets have a strong sense of community with clear norms, rules, and cultures. Users frequently chat to each other on discussion forums such as the DarkNetMarkets on Reddit, publicly calling out dodgy vendors. Customers who continually ask for refunds, claiming that their goods did not show up, are also likely to be shamed.

“This is the best opium you will try, by purchasing this you are supporting local farmers in the hills of Guatemala.”

There are also websites such as DarkNet Market Avengers that use trained chemists to do random testing of darknet drugs. Users send samples of their drugs to Energy Control, a drug-testing lab funded by community donations. It tests the products and sends the results back to the user. For instance, if LSD is found to be “under-dosed” or heroin is found to contain something dangerous like Carfentanil (an extremely potent synthetic opioid which can be life-threatening), the results are posted on the DNM Avengers site, including details of the specific vendor who sold the product.

The result is that fraudsters on both sides of the market are relatively quickly outed and driven out. As James Martin, author of Drugs on the Dark Net, beautifully puts it, “The darknet is really not dark. Thousands of people hold torches to shine the light on how other people behave. You no longer have to rely on one person but the collective judgments of the entire darknet community.”

Within the next five years, darknet sites could be to street drug dealers what Amazon is to local booksellers or Airbnb is to hotels, even if they do raise different and serious ethical questions. On the one hand, cryptomarkets mean that drugs will be more easily available to more people, which cannot be a good thing. On the other, they reduce the length of the supply chain and some of the risks and criminal behavior associated with conventional drug-dealing.

Either way, the systems work because customers become enfranchised in them. Technology empowers customers to hold vendors to account and, ultimately, it is only trustworthy vendors who will survive. E‑commerce is e‑commerce and, even on the darknet, reputation is everything.

Rachel Botsman is the author of Who Can You Trust? How Technology Brought Us Together and Why It Might Drive Us Apart. She is a regular contributor to Wired, as well as The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Guardian, and many other publications. In 2017, she was named as one of the top 50 most influential thinkers in the world by Thinkers 50.

Excerpted from Who Can You Trust? How Technology Brought Us Together and Why It Might Drive Us Apart. Copyright © 2017 by Rachel Botsman. Reproduced with permission from Hachette Book Group.

Original Lead Image: H. Armstrong Roberts / ClassicStock / Getty Images