To a distraught parent whose child has gone missing, the unique genetic code embedded within every cell of the human body is of particular value. That code, spelled out in A’s, C’s, T’s, and G’s, may reveal that their loved one is among the anonymous dead. Hundreds of thousands of people disappear every year around the world because of natural disasters, wars, crimes, and treacherous journeys to other countries. They often leave behind family members, who now may turn to an international organization that specializes in decoding the identities of the deceased.

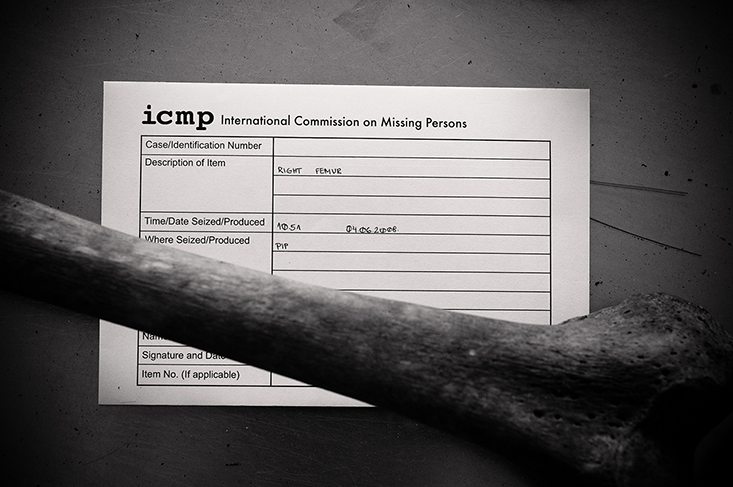

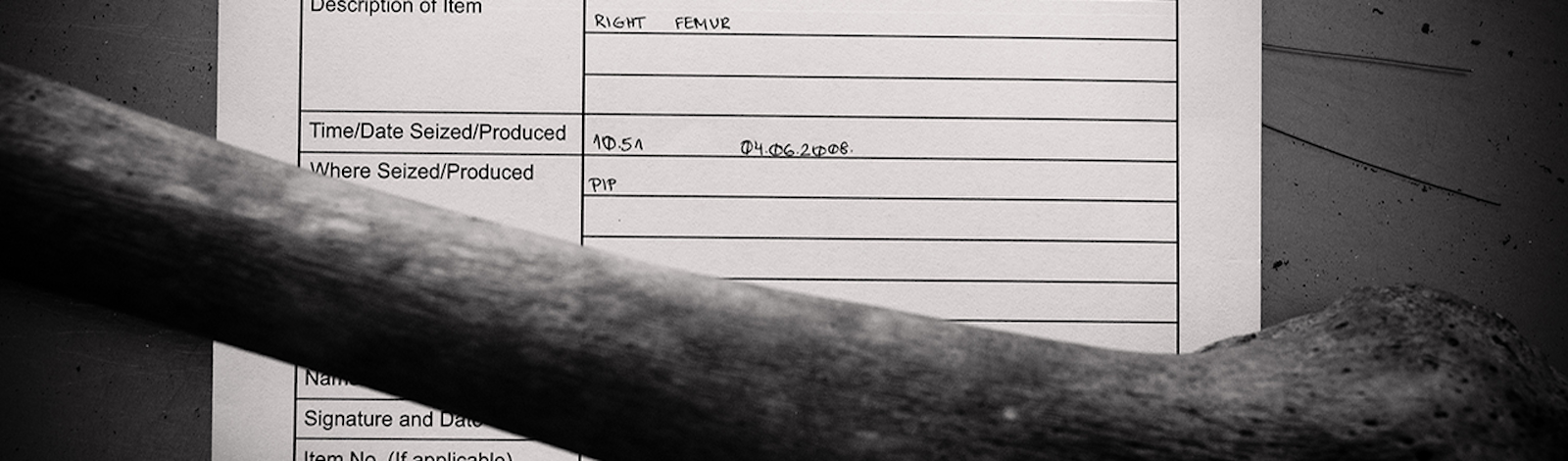

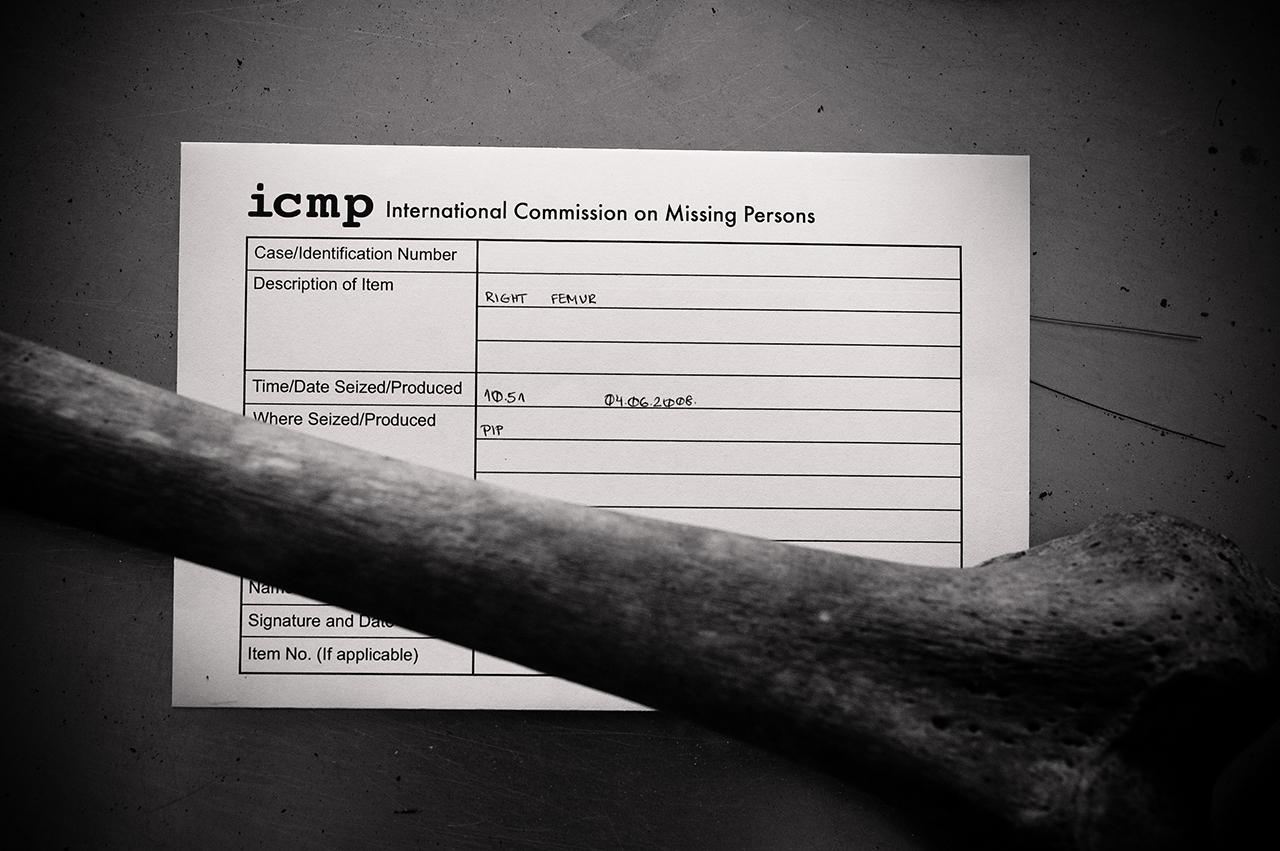

The Bosnia-based International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP) formed in 1996 at the behest of former United States President Bill Clinton, with the aim of identifying thousands of people who went missing during conflicts in Bosnia, Croatia, and the former Republic of Yugoslavia. Many of the bodies recovered from that period had been mangled beyond recognition, so the ICMP established a system for extracting DNA from bones and matching it to DNA donated from people from the region. The group identified nearly 17,000 missing individuals. They have gone on to analyze DNA from victims of the South Asian tsunami of 2004, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Typhoon Frank in the Philippines in 2008, and people who “disappeared” during Pinochet’s reign in Chile. Nautilus caught up with the director of forensic science at the ICMP, Thomas Parsons, to learn what goes into these investigations.

How do you identify a person by their DNA?

One way would be to compare the DNA from a recovered body to DNA found on a missing person’s razor, toothbrush, or items like that. Computationally, this gives the most reliable result because you are looking for an exact match. However, misidentifications can happen if someone else used the object. For that reason, we compare DNA samples to those donated from a missing person’s mother, father, sisters, and brothers. We now have a database of almost 90,000 reference profiles against which every DNA profile we get is screened. We do the calculations to determine the statistical surety of the relationship, and we only report it when we are at least 99.95 percent confident that we have a match. If a mother has several missing offspring, the analysis is tricky. We can tell if individuals shared a mother, but DNA alone cannot discern one sibling from another.

Have you learned about relationships that might come as a surprise to the missing person’s family?

We have access to information about how families are related to each other, but we realize how sensitive that can be. We have well-established rules of confidentiality, and firewalls on our databases because it is critical that these incidental findings are not released. In some parts of the world, a woman might be killed for infidelity. If we find that a missing person is related to their mother but not to their supposed father, it would be absolutely unethical to say this is not the father. We would never do that.

Are people reluctant to hand over their DNA?

Occasionally, but most of the time it’s the families who come forward and say they want to do this. They’re often the ones who network among themselves and go to the government and say that they’d like us to look into missing persons. You can’t underestimate the importance of grassroots public outreach. For example, because a large number of refugees from the former Yugoslavia live in St. Louis, Mo., we sent a collection team there. We advertised our services in newspapers, and then word about us circulated among the broader community.

Are some remains too deteriorated for DNA analysis?

Yes. We are dealing with highly degraded DNA, and in many cases, the only thing left are skeletal remains. In general, DNA from heavily burned bodies or from people buried in hot and wet environments with lots of microbial activity is in worse shape than DNA collected from cold and dry places. However, it’s almost always worth seeing what you can get. Every year we improve our techniques by staying up to date on the latest methods for sequencing ancient, degraded DNA. The methods that scientists use to retrieve DNA from humans that lived thousands of years ago are similar to the techniques we use for assessing DNA from deteriorated bodies that were mangled or not properly buried. Recently, we successfully obtained DNA profiles from severely burned victims of the train crash explosion in Lac-Megantic, Quebec.

We’re also excessively cautious about contamination because the techniques we use detect minute quantities of DNA. If the researcher sequencing the sample sticks their thumb in a test tube, they’ll sequence their own DNA instead of that from the sample. So we use gloves, masks, dust-proof hoods, and in addition we include the DNA from anyone who works at our facilities in our database. That way, if a sample matches one of them, we’ll know it was contamination. That happens very rarely—a couple of instances in tens of thousands of tests—but when it does we write up a report to figure out what occurred so that we prevent it from happening again.

Are there people who would rather your DNA investigations didn’t exist?

Yes. Political issues are huge. We have been involved in some divisive nationalistic conflicts that involve the prosecution of war criminals, and clearly there are people who would prefer to tell their version of history. Specifically, some of the data we’ve uncovered shows there was systematic mass killing of approximately 8,000 men and boys in the Srebrenica massacre of 1995. It may be used in the United Nations’ criminal tribunal against Radovan Karadžić, ex-president of the Serb Republic, and Ratko Mladić, who was a former military leader. People who are loyal to them argue that there were perhaps just a few hundred or a few thousand deaths, mainly combatants. That’s why online, you’ll see parties that falsely discredit our work.

Another problem is that some people only want to expose the deaths of select groups. For example, as Libya confronts the issue of identifying the missing people in their country, some parties show greater interest in knowing the identity of disappeared people who resisted the Gaddafi regime, rather than loyalists to Gaddafi that also went missing. Families, meanwhile, grieve and want answers no matter side of the conflict their loved ones were on.