Artist James Stanford grew up in Las Vegas in the 1950s and ’60s and witnessed nuclear testing as a boy. In the Las Vegas area, 100 above-ground bombs were released by balloons, usually detonating at 1,000 feet, turning sand to trinitite, the radiation invisible yet enduring. But the radiation also left visible marks in the region, including geological fracturing and erosion in areas of underground testing, as well as cuts into fault lines in the Yucca Flats. The power and devastation of nuclear testing and fallout became the focal point of Stanford’s artistic career.

Most Americans living through the Cold War largely steered clear of recognizing the dangers of proliferating nuclear weapons, preferring to focus on the benefits—such as medicine and industry—that atomic energy could offer modern society. The danger of the drifts of radioactive waste soon became apparent, however, causing widespread fear as it entered the atmosphere, water, and tribal and agricultural land.

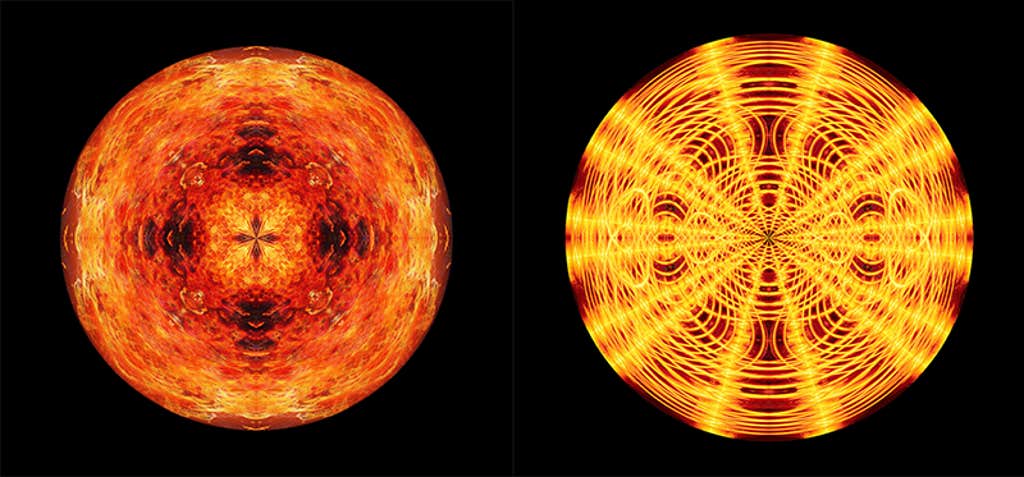

Stanford’s work seems at once an abstract and sublime vision of an exploding sky, and a mediation of the natural world. His images are a phantasmatic expression of humankind’s scientific and military power enacted on a landscape which is often seen as empty and limitless, a void and porous place. Stanford’s image Atomic Glass confronts the physical effects of nuclear testing on the desert landscape. In his ominously beautiful image, Global Atomic Explosion, Stanford captures the cataclysmic moment of a nuclear explosion, where an impossible orange ring of patterns is framed by night black. In his work Nuke Image Round, we see both moments in time and a window into a view of the universe. He uses the patterns of mandalas as a means to invoke the sacred and potent union of opposites, a call for reconciliation between humankind and the natural world, a quiet withdrawal from science and a return to the organic. ![]()

Adapted from “The Fractured Earth and Sky,” by Rosa JH Berland, in The Atomic Kid, edited by J. Boyer and G. Marmalade.