It’s been said astronomy is a science of the weird: Many studies of the cosmos are concerned with what is out of the ordinary.

A case in point: A new study, which first appeared on arXiv, and has since been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics, suggests that the birthplaces of many planets—protoplanetary disks, rotating platters of dust and gas that form around young stars—are much smaller than we thought, sometimes smaller than the distance between the Earth and the sun. The protoplanetary disk that spawned the Earth’s solar system, by contrast, was large, estimated at many times the distance between Earth and Pluto.

The revelation has some scientists rethinking the evolution of planets.

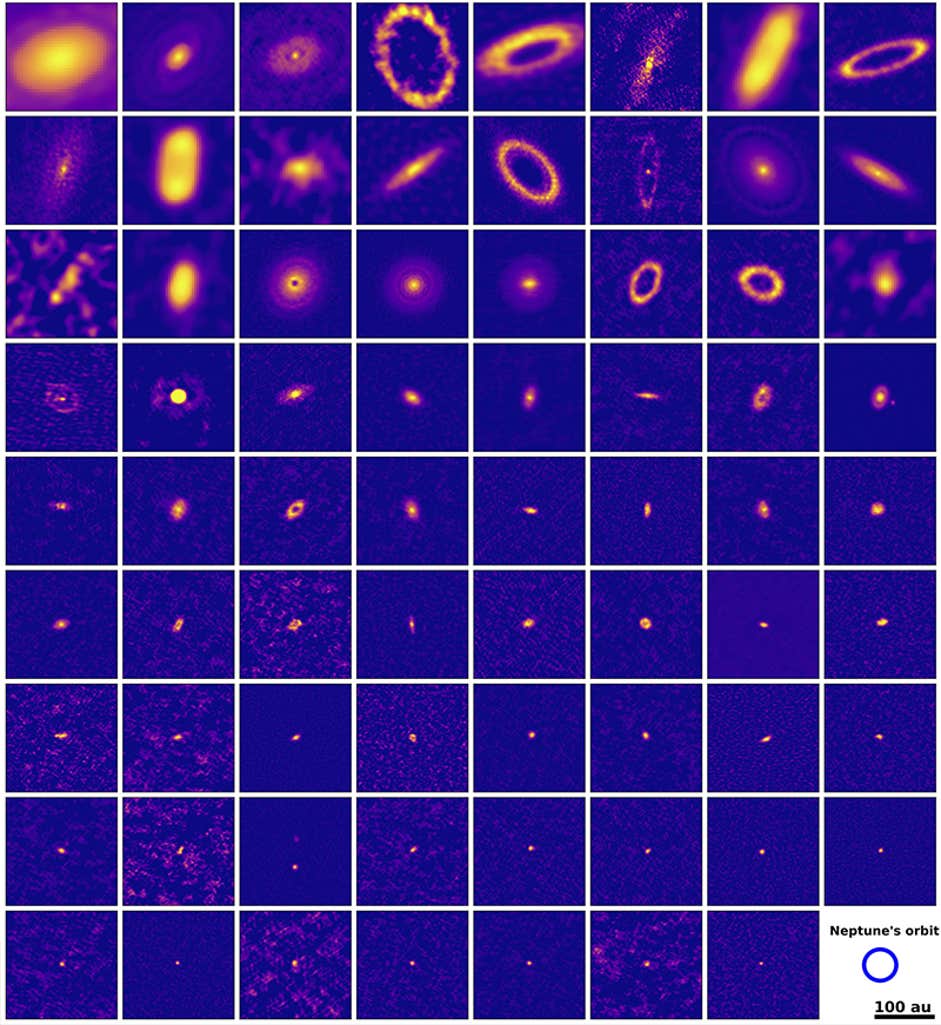

“We did expect to find some small disks, but we didn’t anticipate how many or how small they would be,” says lead author Osmar Manuel Guerra Alvarado, a doctoral student at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands. Guerra Alvarado and his colleagues based their findings on observational data from Chile’s ALMA array—a synchronized group of 66 radio telescopes high on a plateau in the Chilean Atacama desert that is used to study light from some of the coldest objects in the universe, including the cold and dusty outer regions of protoplanetary disks.

The team of astronomers focused on a star-forming region in the direction of the southern constellation Lupus, about 400 light-years from Earth, where approximately two thirds of the 73 protoplanetary disks identified were relatively small, in planet-forming terms—with an average radius of about six times the distance from Earth to the sun, or about the same as the orbit of Jupiter.

We didn’t anticipate how small they would be.

“The findings of the paper show that we have seen only the large, massive end of the distribution so far,” says astrophysicist Til Birnstiel of LMU Munich, an expert on protoplanetary disks who was not involved in the study.

The findings provide an explanation for the abundance of super-Earths—rocky planets between twice and 10 times the mass of Earth—found around distant stars. Small protoplanetary disks favor the evolution of these massive planets as most of the dust is close to the star, where super-Earths are typically found. The researchers found many of these small protoplanetary disks around low mass stars, including the M-type red dwarves, thought to be the most common type of star.

While the findings were unexpected, they corroborate existing theories of planetary evolution, which predict that large disks that do not form planets shrink into more compact structures, Birnstiel says: “This will bring planet-forming material into the inner regions of the disk, possibly aiding rocky planet formation,” he says.

The results of the new study suggest that we on Earth indeed occupy a special place in the universe—at least that our solar system was unusually large at birth. ![]()

Lead image: Guerra-Alvarado et al.