The universe is enormous. By the time you finish reading this sentence, it will be even more enormous.

That’s because the universe is expanding—but not everything is expanding at the same rate. The farther away things are, the faster they’re moving away from us. For every megaparsec (around 3.3 million light-years) of distance from our vantage point, this rate of expansion increases by around 45 miles per second. This rate is known as “Hubble’s Constant,” named after the astronomer Edwin Hubble of space telescope fame, who discovered it in 1929.

Now, astronomers from the University of Tokyo have developed a novel method called “time-delay cosmography” to get a more accurate measure of the Hubble Constant, publishing their findings in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Traditionally, the Hubble Constant has been recorded using “distance ladders.” Astronomers pick a relatively close and familiar cosmic entity—a supernova or star—and observe it, then pick one farther away and observe that, and so on, to measure the rate at which they’re traveling away from us.

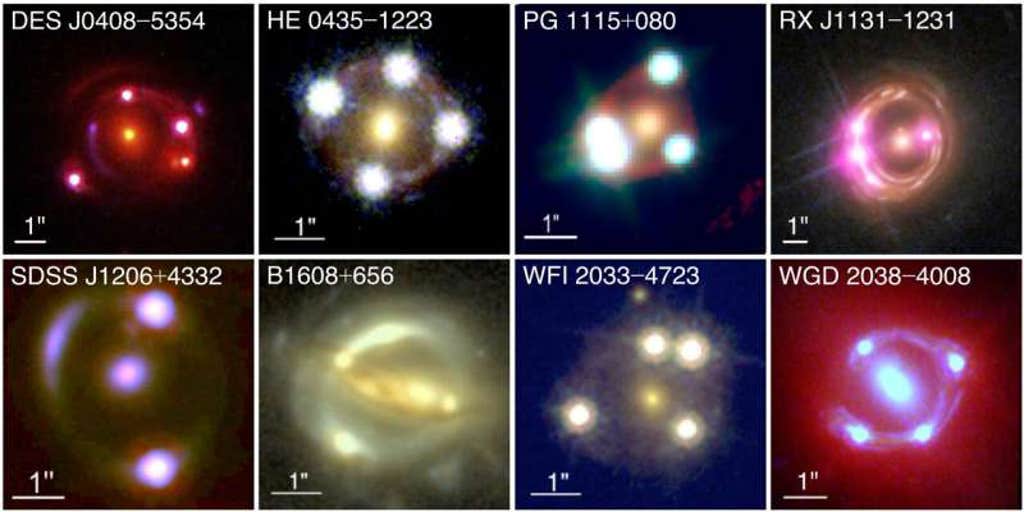

Meanwhile, time-delay cosmography relies on the gravitational lensing of massive objects in space to determine the Hubble Constant. In this method, scientists use a huge galaxy to act as a lens. Super bright objects beyond this galaxy called quasars look distorted because gravity deflects their light. Changes in these distorted images allowed the researchers to measure the difference in time that light from the objects took to reach them.

Using this clever methodology, the authors arrived at a value for the expansion rate consistent with the Hubble Constant. This could help solve a major cosmic kerfuffle.

When astronomers measure this rate of expansion using space telescopes (like the one named after Edwin Hubble), they get one number—around 45 miles/second/megaparsec; when they use another method, measuring the cosmic background radiation generated during the early universe, they get a different, smaller number—around 42 miles/second/megaparsec. This discrepancy is called the “Hubble Tension,” and it has attracted much debate about whether it was due to experimental error, or the actual physics of the universe.

Read more: “How Much More Can We Learn About the Universe?”

“Our measurement of the Hubble constant is more consistent with other current-day observations and less consistent with early-universe measurements,” study co-author and University of Tokyo astronomer Kenneth Wong said in a statement. “This is evidence that the Hubble tension may indeed arise from real physics and not just some unknown source of error in the various methods.”

Still, the team stressed that they’ll need to further refine their time-delay cosmography method to get more precise results. Its current precision is at about 4.5 percent, but it would need to reach a precision of around 1 to 2 percent “to really nail down the Hubble constant to a level that would definitively confirm the Hubble tension,” said study co-author Eric Paic, also at the University of Tokyo, in the statement.

The only real constant in astrophysics? More research is needed. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: ESA/Hubble & NASA, C. Murray, J. Maíz Apellániz