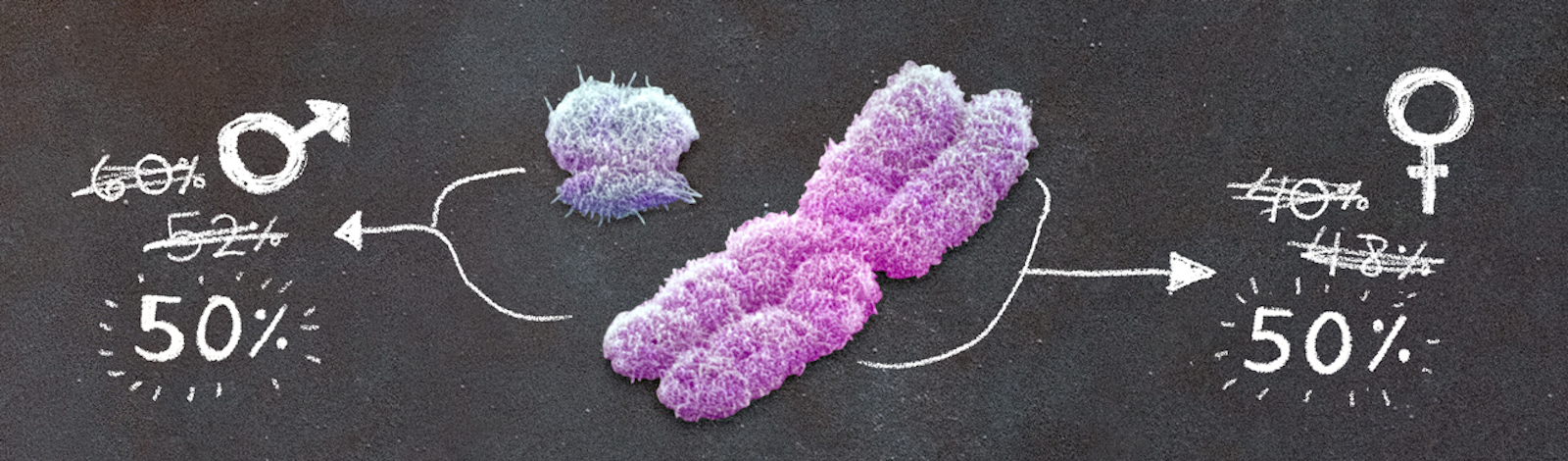

Is it a boy or a girl? That’s what everyone wants to know from the expecting parents. The ratio of newborn boys to girls (called the secondary sex ratio) is a matter of social importance and, occasionally, even national policy. But there is another ratio that, despite being more obscure, is just as important: The ratio of boys to girls at conception, when the egg is fertilized and development begins, called the primary sex ratio.

While the secondary sex ratio is consistently about 106 boys for every 100 girls (or, just 106 for shorthand), the primary sex ratio has been a subject of persistent speculation over the centuries. Naïvely one might expect it to be 100—balanced, equal numbers of boys and girls. To see why it has attracted such attention, suppose it were 125 instead. Since the cells from which sperm are generated start with one X and one Y chromosome, that would mean that one-fifth of the X chromosomes either never make it into functioning sperm, or are prevented from fertilizing an ovum somewhere along the way. This is a huge bias, requiring a powerful but as yet undiscovered biological mechanism.

Or, if sperm are being sex-selected after they are created, that process would likely extend over time. Changes in the timing of intercourse could then have substantial influence on the likelihood of the resulting child being a girl. (Such effects have frequently been claimed, though inconsistent about the direction of the effect, and never conclusively demonstrated.)

At every age, in almost every time and place, a man is more likely to die than a woman.

The primary sex ratio could also speak to how reproductive technologies, nutritional supplements, medications, and environmental chemicals may be shifting the invisible scales of gender, influencing which embryo lives and which dies. Some major pollution exposures are known to cause dramatic changes in the secondary sex ratio: Small but statistically significant declines in the proportion of males born have been observed across several developed countries, including the Unites States and Canada, and there are suggestions that this may be an indicator of disruptive chemical exposures.

The larger the discrepancy between primary and secondary sex ratio, the more of one sex are being lost through a sex-specific mechanism. Making sense of this process would likely guide medical efforts to prevent unnecessary miscarriages. More generally, understanding the primary sex ratio, and the differing trajectories of males and females after conception, are vital clues to the evolutionary forces that have shaped the gender structure of human families, and of human populations.

For all these reasons, the primary sex ratio has been the subject of passionate surmise, but, until recently, little detailed knowledge. That’s because the fates of the embryonic population are almost indiscernible. Various estimates put the fraction of fertilized human eggs that are lost in the first trimester of pregnancy between one-third and two-thirds. Many of these do not even survive to implantation in the uterus, so it is questionable whether we should say that the pregnancy has even begun. “Their coming is empty, and their end is darkness,” as the Bible says.

Nevertheless, in a 2008 encyclopedic work by a large international team of psychologists called Sex Differences: Summarizing more than a century of scientific research, the chapter on biology begins this way:

Research regarding the primary sex ratios is largely confined to the study of aborted and miscarried human fetuses. […] These studies indicate that males are conceived at substantially higher rates than females. The degree to which male conceptions outnumber female conceptions has been rated to be as high as 160 to 100 [61.5 percent male] in humans.

The trouble is that this conclusion is completely wrong, something which modern data has now amply proved.1 That it remained the standard account over a century, despite its inherent implausibility, is a valuable lesson in the tunnel vision of otherwise conscientious experts, and in how a fact sufficiently repeated becomes its own confirmation. And it is a story of how scientists can assemble clues—clues that were already known but never put together in the right way—to solve a centuries-old mystery, and reveal what was an unobservable truth of human life.

Being male is a dangerous thing. You may already know that pubescent young men expose themselves to unnecessary danger of violence or accidents, and suffer excess mortality. But it goes well beyond that: At every age, in almost every time and place, a man is more likely to die than a woman, and according to a recent study of data over two centuries in 13 different developed countries, the male handicap has been increasing throughout the 20th and into the 21st century. For example, in 2013 about 15 out of 10,000 U.S. women between 40 and 44 died, but for men the number was 25. In the same year 54 out of 10,000 infant girls and 65 out of 10,000 infant boys died. Similar differences are found for 10-year-olds and septuagenarians.

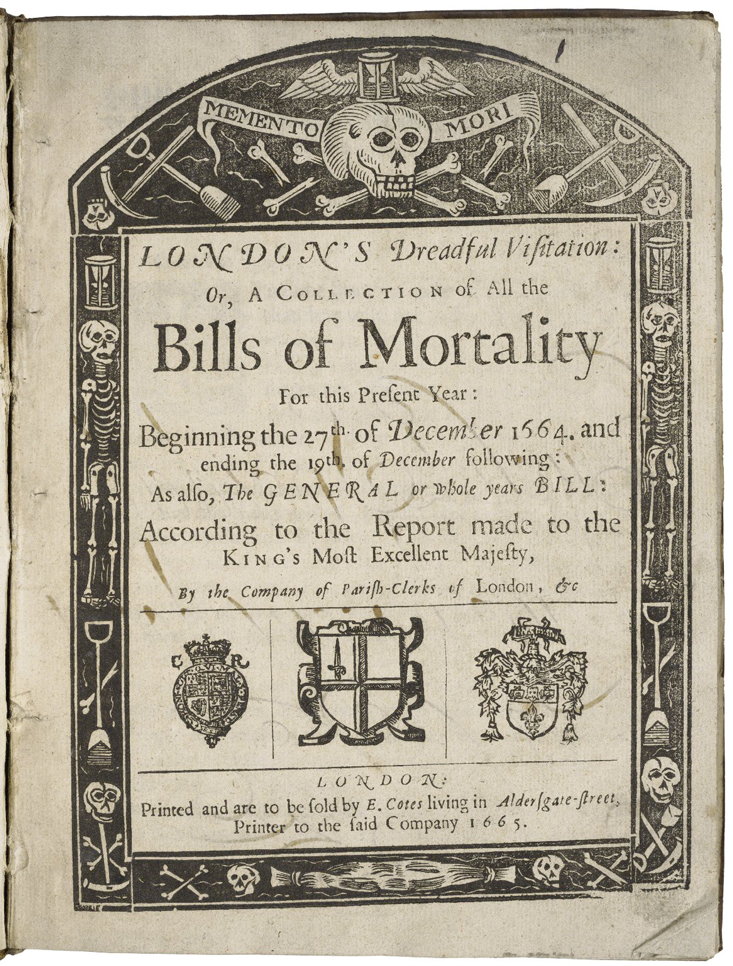

The peculiarly male tendency to expire early has been known for centuries. In 1662 the London haberdasher and part-time philosopher John Graunt published his Natural and Political Observations Made upon the Bills of Mortality, one of the most revolutionary books that you have probably never heard of. In addition to mining the hitherto unregarded registers of deaths in London—gathered for the purpose of identifying outbreaks of plague—Graunt combined them with other sources of data, such as church records of burials and christenings, to paint a statistical portrait of life and death in Restoration-era England. He remarked:

There have been Buried from the year 1628, to the year 1662, exclusive, 209,436 Males, and but 190,474 Females;[…] there have been also Christned within the same time, 139,782 Males, and but 130,866 Females, and that the Country Accompts are consonant enough to those of London upon this matter.

There are three striking observations here: First, there are nearly equal numbers of male and female births; second, they are not exactly equal, the sex ratio in London being about 107; third, that the sex ratio of London births is similar to that found elsewhere in England.

The excess male births, Graunt suggests, are just enough to compensate for the larger number of men who emigrate or die young (in wars, accidents, and “by the hand of Justice”), leaving an equal number of young adult males and females. That explanation was very much the standard one for the following two centuries.

In 1840 Christoph Bernoulli extended what is now called the “fragile male” hypothesis back beyond birth, to the moment of conception. Having observed that more male than female fetuses were stillborn or miscarried, Bernoulli inferred that the small excess of males born (51.5 percent) must be the residue of a larger excess of males conceived. Through careful calculation—though he admitted that he could barely do more than guess at the crucial number for the calculation, the total miscarriage rate—he estimated that 52 percent of the embryos conceived would be male, a sex ratio of 108 males conceived for every 100 females.

This informed the conventional wisdom for another two centuries. The Russian statistician Alexander Tschuprow noted early in the 20th century that the male fraction of miscarriages seems to increase the further back in pregnancy you look—sometimes referred to as “Tschuprow’s law.” Combined with awareness of a much higher rate of loss early in pregnancy, Tschuprow’s law led to estimates of 60 percent or more male at conception.

Statistical speculation became a textbook truth that is repeated even to the present day. If you weren’t a specialist in the matter, if you weren’t even aware of the male tilt at birth, you might naïvely disagree with the experts. You might conjecture that there were probably the same number of boys conceived as girls. If you knew a bit more, that sex is determined by whether an X-bearing or Y-bearing sperm accomplishes the fertilization, and that there are (at least initially) equal numbers of each, the presumption of equality would seem even more plausible. Until recently most people educated in medicine or demography or human biology would have tut-tutted and explained why things just weren’t so simple. But you would have been right, and the experts wrong.*

Many mistook their rough estimates for precise truth, and then added a dollop of biased speculation on top of them.

One way to get a handle on the sex ratio early in pregnancy is through a meta-analysis of existing studies of sex ratios in induced abortions. When we look only at the studies with karyotypic sex identification—actually identifying the sex chromosomes of the embryo, so the most reliable, unbiased method—we see a sex ratio that appears actually to be predominantly female in the earliest weeks, with the male proportion rising through the first trimester. While the numbers are too small to make a very precise estimate of the trend, it is clear that there is no evidence of large male excess. Consistent with this, studies of early miscarriages with modern methods of sex identification have tended to find more females than males.

Modern mass prenatal testing gives us new tools and new data. Analysis of the results of 61,000 pregnancies with chorionic villus sampling between 8 and 14 weeks found 51.4 percent male fetuses (sex ratio 105.7), while more than 800,000 amniocentesis results between 12 and 22 weeks found 50.6 percent male (sex ratio 102.4). These are slightly inconsistent, and may reflect some small biases due to the screening that selects women for these tests. But again, there is no evidence of a sex ratio at any time that is substantially above the well-known typical sex ratio of 106 at birth.

With current or foreseeable technology there is no way to make any direct measurement of the sex ratio closer to conception. Instead, we turn to embryos from assisted reproductive technology clinics, which help couples with difficulties having children on their own. The procedures carried out in these clinics typically involve in vitro fertilization and often include preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) in order to improve the chances of a successful pregnancy by eliminating embryos with an abnormal complement of chromosomes. A sample of 140,000 3- to 6-day-old embryos analyzed for genetic defects in PGD was consistent with an exactly balanced sex ratio (100.8±1.2) at conception.**

The unavoidable conclusion of the data is that the first trimester of pregnancy is a unique exception to the “fragile male” rule, the principle stating that males have higher mortality than females of the same age. In fact, when we look more closely at our PGD embryos, we see that males are overrepresented among those with missing or extra chromosomes. These chromosomally defective embryos are almost invariably fated to miscarry, most of them even before implantation, so the males are starting out at an actual deficit. Among those with the correct complement of chromosomes, perhaps 49.3 percent are male. Over the course of about three months there must be very substantial excess female mortality, resulting in something close to the birth sex ratio of 51.5 percent males remaining by about 15 weeks into the pregnancy.

We don’t know anything more precise about when this occurs. We also know next to nothing, as yet, about the mechanism that raises female mortality. There might be an inherent difficulty confronted by female embryos in this stage of their growth—perhaps related to the process of deactivating one X chromosome. Alternatively, there might be an imbalance in the mother’s mechanism for measuring the embryo’s fitness, and for weighing the risks against the benefits of continuing the pregnancy.

What is clear, though, is that the primary sex ratio is within spitting distance of 100.

Why were the earlier estimates so far off the mark? Most of the data that went into the current estimates depend on technologies and practices in reproductive medicine—in vitro fertilization, chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis—that were not available until fairly recently. What is hard to explain is not that earlier researchers were unable to pin down the primary sex ratio precisely. What is hard to explain is that so many mistook their rough estimates for precise truth, and then added a dollop of biased speculation on top of them. Abortion data, the only direct window into the early sex ratio, were biased toward overestimating the number of males until the technological developments in chromosomal analysis in the 1970s. These biases were suspected, but tended to be ignored. Beyond that, there was colossal statistical variation in the estimates, unavoidable given the small numbers—generally under 1,000, sometimes fewer than 100—of embryos examined in any individual study. But while the studies of a few hundred embryos finding 60 percent males made it into the textbooks, the studies finding 40 percent males tended to be neglected. It is hard to see any excuse for this other than the human tendency to neglect to notice evidence that contradicts what we think we already know to be true.

In the days when divine providence was widely accepted as a sufficient and even satisfactory explanation for the world’s fine structure, the roughly equal numbers of adult men and women were seen as demonstrating God’s plan for human monogamy. Such a theory was already suggested by John Graunt, but was first developed at length by the Scottish physician John Arbuthnot in 1710, in his essay “An Argument for Divine Providence, Taken from the Constant Regularity Observed in the Births of Both Sexes,” which is also generally considered to be the first work to present a formal statistical test of a scientific hypothesis. What satisfied the curiosity of the 18th century was insufficient in the 19th, though.

Darwin himself addressed the question of the evolution of the sex ratio in the first edition of The Descent of Man, arguing that natural selection should tend to equalize the numbers of male and female offspring. He later had misgivings, however, and in the second edition he dropped the argument and offered an apology that “I now see that the whole problem is so intricate that it is safer to leave its solution for the future.”

Darwin’s original argument was similar in spirit to what is accepted today. In the mathematical form first worked out by German biologist Carl Düsing, it begins with the elementary fact that each offspring has one mother and one father, and that they make equal genetic contributions. Consequently, half the ancestry of future generations come from females and half from males. Suppose that there is just a single generation each year, as in many insects or annual plants, and that a total of F females and M males are conceived. Then, on average, each female can expect to make a fraction 1/F of the genetic contribution of females, and each male can expect to make a fraction 1/M of the genetic contribution of males.

Now, if F M, a parent makes a larger contribution to future generations by producing a female (or a male if the reverse is true). Since evolution selects for organisms that are more likely to pass on their genes, a heritable tendency to produce females in excess is favored when there are more males than females in the population, and vice versa. This drives the system to equilibrium, which is achieved when F = M.

The roughly equal numbers of adult men and women were seen as demonstrating God’s plan for human monogamy.

The British statistician R.A. Fisher extended this argument in 1930 by allowing for the possibility that female and male offspring may place different demands on the limited resources available to parents. (His book neglected to mention Darwin, Düsing, or any other predecessor, as a consequence of which the idea has come to be known as Fisher’s Principle.) He showed that natural selection favors equal investment in the two sexes rather than equal numbers. In a world of scarcity, parents are selected to maximize offspring fitness per unit cost rather than offspring fitness itself.

The trouble is that investment in offspring can be hard to calculate. Not surprisingly, we have no reliable estimates of total investment in each sex for humans. Most species have a well-defined period of parental investment after which offspring lead independent lives. In social species, and notably among humans, resource transfers among family members or more inclusive groups may continue throughout life. Human children also begin to contribute to the household economy as they grow older. All of this makes it difficult to clearly define the human period of parental investment.

We don’t know whether the balanced primary sex ratio reflects an inflexible sex-determination system, or an optimal investment strategy favored by natural selection. Whereas an unbalanced sex ratio calls out for explanation, including the possibility that natural selection has been at work, a balanced sex ratio offers only ambiguous testimony at best. It is the default outcome of the XY mechanism of sex determination: X- and Y-bearing sperm are produced in equal numbers and should have equal chances of fertilizing an egg. If the XY system, which is common to all mammals, were simply incapable of producing primary sex ratios other than 100, there would be no heritable variation or natural selection on the primary sex ratio.

Either way, we now know that the 100 ratio forms the background for the trajectory of sex ratio through gestation and beyond. We now know, as well, that there is a complicated back-and-forth of sex ratio through the nine months, and also that the sex ratio at birth varies with environmental factors, including levels of stress and pollution, in ways that may be adaptive.

“The history of a man for the nine months preceding his birth,” remarked Coleridge, “would, probably, be far more interesting, and contain events of greater moment, than all the threescore and ten years that follow it.” It is not just nine months of life that precede birth, but also nine months of death. This death shapes and selects those who survive to birth, and go out into the world.

The old story of high primary sex ratio— as high as 282 (74 percent male) by some accounts—declining rapidly and then steadily to birth, is gone. Any sex ratio much higher than 108 (52 percent male) at any time during pregnancy is essentially excluded by modern data. Past the middle of the second trimester the sex ratio is known with great accuracy, at least in industrialized countries with strong health systems and reliable vital statistics, because nearly every fetal death after that point is recorded. The sex ratio of 20-week fetuses is essentially identical to the secondary sex ratio: The numbers of deaths after that point is too small to make much difference, even if the stillborn were all male.

One immediate consequence is that any new medical intervention that reduces the number of miscarriages in the first trimester may reasonably be expected to rescue more female than male embryos, subtly shifting the sex ratio at birth and into the future. Preventing later miscarriages and stillbirths would increase the number of boys.

Data from new screening practices, which extract fetal DNA circulating in the mother’s blood, likely will sharpen our picture of the first few months. Combining this with individual genomic data would help to gauge the heritable variation in sex ratio trajectory relatively soon after conception, that would be available to natural selection.

Even knowing the primary sex ratio and the trajectory to birth in great detail only brings us to a first base camp for a whole new range of explorations. Is the primary sex ratio the same in all human populations at all times? How much variability in primary sex ratio is possible among related species with similar modes of sex determination? What mechanisms disadvantage female survival in the first three months, and male survival beyond that?

There are broader questions, too: Is the fluctuating mortality of males and females mere biochemical exigency, or is it linked to forgotten catastrophes and everyday demographic stresses of prehistory? Is there really a residue of sex adjustment in response to environmental conditions in modern humans, and if so, why, and why so little? And, that long-standing question: Why does human life begin with so much death?

David Steinsaltz is an associate professor of statistics at the University of Oxford. He blogs at Common Infirmities.

J. William Stubblefield is an independent biologist.

James E. Zuckerman is an assistant professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Footnotes

* Not all of the experts, to be sure. The 1971 textbook The Physiology of Human Pregnancy by Frank E. Hytten and Isabella Leitch includes an appendix on “The Sex Ratio,” beginning “It has long been accepted that there is a considerable preponderance of males, a high sex ratio at conception. Such estimates were almost certainly mistaken and probably arose from the superficial similarity of male and female genitalia at that early stage of development.” Embryologist M. R. Creasy noted in 1977 the paucity of evidence for the male-biased primary sex ratio, and another embryologist, Charles Boklage, attacked its theoretical basis in 2005.

** At first glance, it might not seem clear what relevance assisted reproductive technology conceptions might have for the sex ratio of naturally conceived embryos. After all, the theories put forward to explain the putative male excess at conception typically appeal to some differential influence of changing hormone concentrations during the fertile period, or some bias in the sperm’s odyssey through the birth canal to the Fallopian tubes where fertilization normally occurs. Other interventions in the ART practices, including PGD, and the selection of couples with fertility problems to undergo these procedures, could influence our estimate of the primary sex ratio. On the other hand, the secondary sex ratio of in vitro fertilization births is known to be essentially identical to that derived from natural conceptions. Since the post-implantation course of pregnancy is similar for both kinds of births, identical secondary sex ratio probably implies a similar primary sex ratio.

Reference

1. Orzack, S.H., et al. The human sex ratio from conception to birth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112, E2102-E2111 (2015).

Photo: Andrew Syred / Science Source