Space mining is no longer science fiction. By the 2020s, Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries—for-profit space-mining companies cooperating with NASA—will be sending out swarms of tiny satellites to assess the composition of hurtling hunks of cosmic debris, identify the most lucrative ones, and harvest them. They’ve already developed prototype spacecraft to do the job. Some people—like Massachusetts Institute of Technology planetary scientist Sara Seager, former NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver, and science writer Phil Plait—argue that, to continue advancing as a space-faring species, we need to embrace this commercial space mining industry, and perhaps even facilitate it, too. But should we?

This question concerns me, as both an astrophysicist and a space enthusiast. Before becoming a science communicator, I worked for 15 years researching the evolution of galaxies, the properties of dark matter, and the expansion of the universe. From that perspective, the distance from us to the asteroid belt is actually rather small, so the question of whether to mine it, and in what way, hits close to home. The Space Act of 2015, a U.S. law passed last fall, authorizes the president “to facilitate the commercial exploration and utilization of space resources to meet national needs.” It’s an exciting prospect, to be sure, but also a troubling one.

For one thing, it appears to violate international law, according to Congressional testimony by Joanne Gabrynowicz, a space law expert at the University of Mississippi. Before NASA’s moon landing, the United States—along with other United Nations Security Council members and many other countries—signed the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies,” it states, “is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” The 1979 Moon Agreement went further, declaring outer space to be the “common heritage of mankind” and explicitly forbidding any state or organization from annexing (non-Earth) natural resources in the solar system.

Major space-faring nations are not among the 16 countries party to the treaty, but they should arguably come to some equitable agreement, since international competition over natural resources in space may very well transform into conflict. Take platinum-group metals. Mining companies have found about 100,000 metric tons of the stuff in deposits worldwide, mostly in South Africa and Russia, amounting to $10 billion worth of production per year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. These supplies should last several decades if demand for them doesn’t rise dramatically. (According to Bloomberg, supply for platinum-group metals is constrained while demand is increasing.)

Palladium, for example, valued for its conductive properties and chemical stability, is used in hundreds of millions of electronic devices sold annually for electrodes and connector platings, but it’s relatively scarce on Earth. A single giant, platinum-rich asteroid could contain as much platinum-group metals as all reserves on Earth, the Google-backed Planetary Resources claims. That’s a massive bounty. As Planetary Resources and other U.S. and foreign companies scramble for control over these valuable space minerals, competing “land grabs” by armed satellites may come next. Platinum-group metals in space may serve the same role as oil has on Earth, threatening to extend geopolitical struggles into astropolitical ones.

NASA’s increasing collaboration with space mining companies could distort and divert efforts previously focused on space exploration.

Moreover, the technology that might enable this free-for-all—versatile “nanosatellites,” no larger than a loaf of bread—is relatively inexpensive. In December, while reporting for a story about these tiny satellites, also known as CubeSats, I came across some missions applicable to mining asteroids. In mid-2018, NASA will launch a satellite for a mission called Near-Earth Asteroid Scout, for example. It will deploy a solar sail, propel itself with sunlight, and journey to the asteroid belt, where it will scope out a particular asteroid and analyze its properties. Last June, NASA also awarded grants to Planetary Resources to advance the designs of spectral imagers and propulsion systems for CubeSats, and other missions will develop the satellites’ abilities to communicate and network with each other. NASA also awarded Deep Space Industries contracts to assess commercial approaches for NASA’s asteroid goals, which may involve hosting DSI’s asteroid-prospecting equipment on its missions.

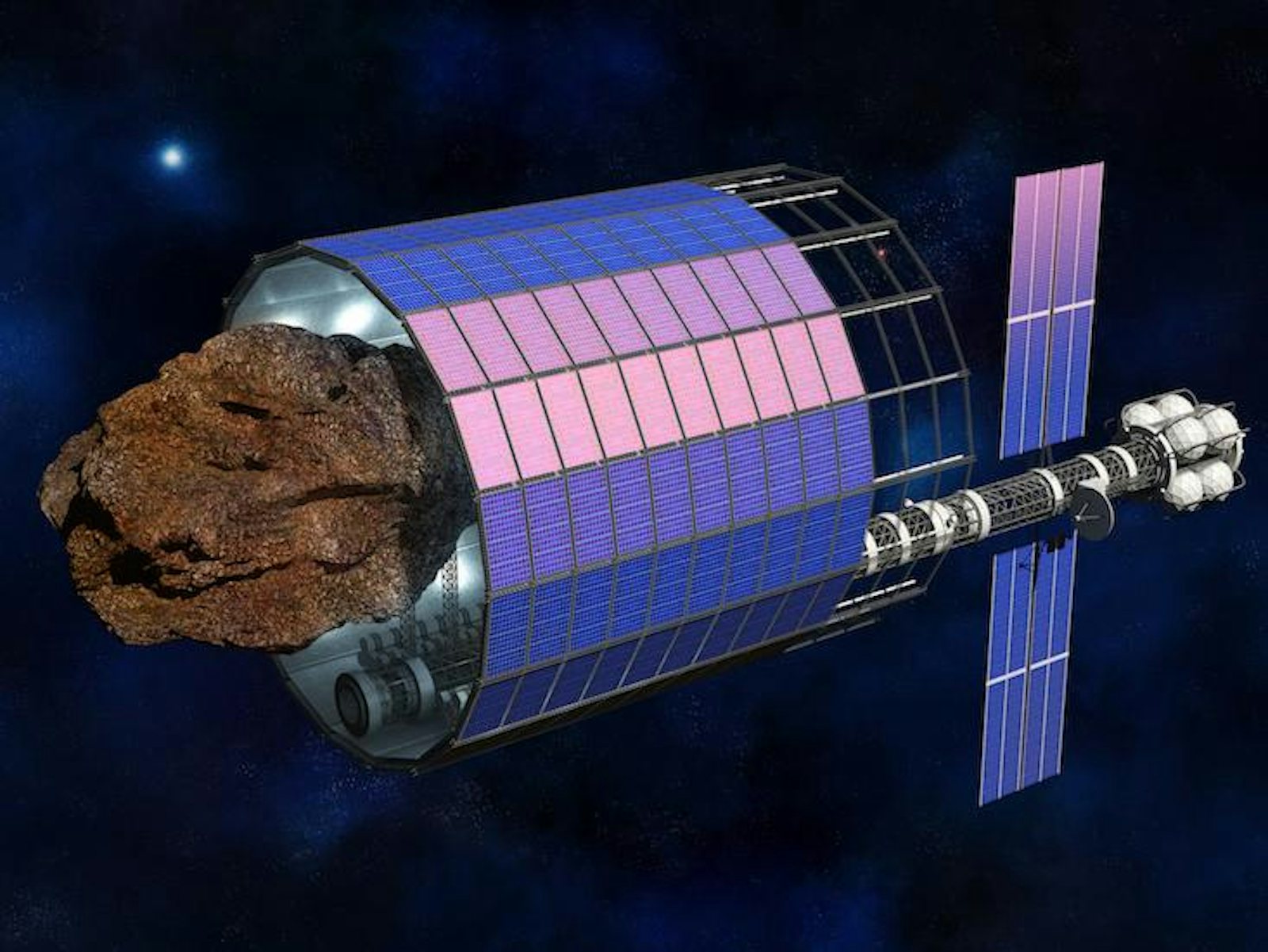

Like all forms of mining, it will be dangerous. If space-mining activities break up asteroids, the resulting debris could be hazardous for satellites, other spacecraft, and astronauts nearby. On the other hand, in a best-case scenario, space mining could be environmentally safe, capture only necessary minerals and water, and, in the more distant future even lead to the construction of a far-flung space station led by NASA and other space agencies, orbiting 200 million miles from Earth and serving as both a mining depot and a pit-stop for passing spacecraft.

But it’s not clear that a pact between the commercial space mining industry and NASA would align with the public’s interest. NASA’s increasing collaboration with space mining companies could distort and divert efforts previously focused on space exploration and basic research, and discourage public interest and engagement in astronomy.

Last October, for example, Seager advocated for space mining at a science writing conference I attended. She’s part of a motley group of advisors for Planetary Resources, including the movie director James Cameron, a lawyer for a prominent Washington D.C. firm, and Dante Lauretta, another astronomer whom I respect. Seager seems to believe that encouraging private space mining will lead to more investments and technological innovation that would enable more scientific research. In a 2012 interview with The Atlantic, for instance, she said, “The bottom line is that NASA is not working the best that it could for space science right now, and so in order for people like me to succeed with my own research goals, the commercial space industry needs to be able to succeed independently of government contracts.”

But if the U.S. and U.S.-based companies lay claim to the richest and most easily accessible prospecting sites, not allowing other companies and nations to share in the wealth, economic and political relations could be damaged. That’s why this seems to be a dangerous path for space explorers. Once you’re on board with the commercial space industry, then you as a researcher must accept, if not support, everything that comes with it. Seager and a few other researchers may be willing to take this risk, but what about the rest of the space science community? Moreover, to succeed, these businesses will seek profitable missions, while science, exploration, and discovery—goals that stimulate public interest—will inevitably have lower priority. (Other commercial spaceflight companies, like Elon Musk’s SpaceX, do generate public interest, but they’re not directly involved in mining asteroids.) NASA may have its shortcomings, but at least its missions and research goals answer to the public. It’s not exactly a welcome thought to imagine more and more of our presence and activity in space being ceded, with NASA’s help, to private industry.

What should happen instead? Commercial space mining and science would both be served well by decoupling from each other. We should treat outer space like we do Antarctica. That icy landscape is humankind’s common heritage, where we encourage scientific investigations and conservation and forbid territorial claims. If some organizations want to mine asteroids, then we should take the time to develop and establish an international framework to regulate it properly.

Space-mining is an exciting opportunity to articulate our species’ role in our little galactic fragment. But it’s not just about sustainably managing limited or dwindling resources. It’s about our interactions with the nature beyond our humble world. We should explore the solar system as its steward without repeating our economically rapacious past.

Ramin Skibba is a science writer and astrophysicist based in Santa Cruz and San Diego. He can be found at raminskibba.net and on Twitter at @raminskibba.