In Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2017 science-fiction novel New York 2140, the city of the future has become a vertical super-Venice, after being flooded by rising seas caused by global warming melting the Arctic ice caps.1 While the lower stories of many of Manhattan’s skyscrapers have been overtaken by the sea, residents continue to live in those above, accessing them via boathouses and pontoons. A tangle of sky-bridges connect the lofty heights of many of these skyscrapers, the streets beneath now canals traversed by countless boats and gondolas. Ruins litter the intertidal zone, inhabited by the desperate and the poor; while airships agglomerate above the buildings into sky villages. Robinson’s imagined New York of the future hasn’t succumbed to the ravaging effects of climate change; rather, it has adapted to the changes by radically reshaping its built environment.

Despite the fact that climate change is already affecting vulnerable cities like New York—principally featuring an increased incidence and severity of urban flooding—it remains a phenomenon that is dominated by future predictions. Even by the cautious estimates of the most recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 2014, cities are in for a rough ride in the next century. By 2100 the rise in global temperatures is almost certain to exceed 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels, and, alarmingly, already reached that level for a short time in early 2016. Sea levels will rise by anything up to a meter, or more if current predictions prove to be over-optimistic (and New York 2140 is based on an estimated rise of 15 meters, or 49 1/4 feet, over the next 100 years). At the same time, the oceans will also warm and become more acidic; and the turbulence of the atmosphere will intensify, leading to more extreme weather events and a greater risk of flooding.2 Cities are especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change, particularly coastal or tidal-river-based conurbations—including 22 of the world’s major cities according to the Stern Review of 2006.3

As much as these climate reports are grounded in empirical evidence, they are nevertheless essentially predictive, laying out a whole host of possible futures that rely on our ability to imagine those futures, even with the help of a welter of facts and figures.4 The overwhelmingly future-oriented language of climate change is perhaps the principal reason why it has been and continues to be so difficult to find common agreement as to how to act in the face of such fundamental uncertainty.5,6 It is no wonder then that the focus of much of the current thinking on climate change and cities is on mitigation rather than adaptation, and this formed the focus of the landmark international climate change agreement in Paris at the end of 2015.7 Even the emerging body of literature on climate change and urban resilience, which seeks to shift the focus from mitigation to adaptation, remains firmly grounded in instrumental thinking—whether adaptation of the built fabric through long-term strategic planning, or reshaping of urban governance and socio-political life toward sustainable ends.8 While these objectives are laudable, what is underplayed in much of this work is the role of the creative imagination in thinking through the relationship between urban futures and climate change. As New York 2140 shows us, the imagination can be a powerful tool for articulating radical new possibilities for urban life in the face of equally radically uncertain futures.

One of the most striking images of London in ruins is an engraving by Gustave Doré from 1872, which was the final illustration in William Blanchard Jerrold’s book London: A Pilgrimage. Depicting what was then the world’s largest city—and the center of a global empire—Doré’s image was a late expression of the 19th-century obsession with the figure of the “New Zealander,” an imagined New World successor to the British who would, in the far distant future, come to gaze upon the ruins of London just as Victorian travelers gazed upon those of ancient Rome.9,10 It is also a powerful image of submergence: the city slowly succumbing to ruin from above—its buildings sinking into the ground—and below, from the waters of the river Thames, long released from its human-made embankments.

Despite the fact that climate change is already affecting vulnerable cities like New York it remains a phenomenon that is dominated by future predictions.

Tapping into late 19th-century anxieties about both imperial decline and London’s seemingly intractable social divisions, this image has persisted as an early precursor to cinema’s enduring obsession with picturing urban destruction. Apocalyptic flood disaster films, from Deluge (1933) to The Day after Tomorrow (2004), use New York’s landmarks, such as the Statue of Liberty, in the same way as Doré’s image uses the sunken pillars of Blackfriars Bridge and the ruined dome of St Paul’s Cathedral beyond, to provide memorable visual reference points for wholly unfamiliar doomsday storylines.11,12 The sense of flood waters restoring untamed nature back to the city resonates with cinematic images of post-apocalyptic cities, perhaps most notably New York in I Am Legend (2007) and London in The Girl with All the Gifts (2016). Indeed, these two aspects of deluge imagery—the apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic—mirror the two strands already identified above in relation to fiction, namely the imagination of cities after a catastrophic flood and those that focus on the flooding event or events themselves. These images tend to emphasize, on the one hand, the experiences of a solitary survivor (the New Zealander in Doré’s image) and, on the other, the attempts by urban inhabitants to come to terms with flooding, even if, in the cinematic tradition, this usually focuses on rebuilding cities rather than adapting to their submergence.

In relation to more recent predictions about the impact of sea-level rises on low-lying cities, visual imagery is characterized by two dominant viewpoints, namely from above and below the flood waters. Views from above include the predictive flood maps issued by the U.K. Environment Agency—conventional map views of cities like London overlaid with swathes of blue indicating areas at risk from future flooding—and more creative adaptations of maps seen in Jeffrey Linn’s series of sea-rise maps, in which the artist has shown how world cities such as London, Los Angeles, Vancouver, and Hong Kong would virtually disappear if sea levels rose by 66 meters (217 feet), the highest level currently predicted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.13 Views from above also include bird’s-eye views of cities showing how sea-level rises will alter the sky- and shore-lines, as well as the riverscapes, of iconic urban areas—for example, John Upton’s digital photomontage of Manhattan skyscrapers used in Al Gore’s polemical film An Inconvenient Truth, released in 2007.

There is no doubting the powerful effect such imagery can have. It provides a dramatic at-a-glance picture of what cities might look like if flooded by rising sea levels. Yet it also distances viewers from the catastrophic effects of flooding on the ground. What we see in these images are effectively stage sets—cities emptied of their inhabitants and submergence as an inevitable and unstoppable apocalyptic event, even as the process leading to flooding on such a scale would probably take centuries to work itself out.

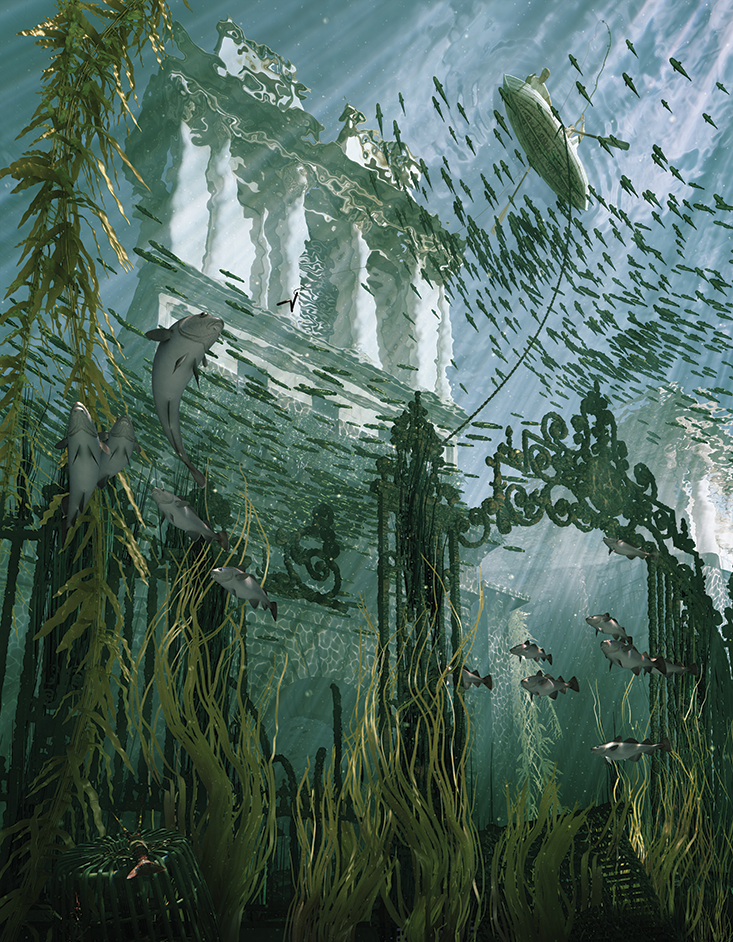

Views from below are less common than those from above, probably because it is much more difficult to imagine living below the flood waters than above them. These views include digital images of submerged cities, such as François Ronsiaux’s Times Square in New York14 enveloped in submarine blue and Nickolay Lamm’s similarly rendered image of Miami under a 7.6-meter (25-foot) rise in sea levels.15 These images present desolate urban vistas, devoid of any life bar the observer, even as the flood waters are rendered crystal clear. In contrast, in one of a series of five images produced by the U.K. media production studio Squint/Opera, London’s future flood waters support a rich marine ecosystem. Looking up from the bottom of a new shallow sea towards the half-submerged church of St Mary’s on London’s Strand, this image provides an unfamiliar counter to the otherwise predominantly pessimistic representations of underwater urban futures.16 Exhibited as part of the London Architecture Festival in 2008, this view from below offers a sense of optimism—in their London of the future, the floods have actually enhanced the urban environment by bringing in abundant wildlife and new opportunities for entrepreneurship.17 Yet, just how such an improved way of life will come about is far from clear in the image, bar the inclusion of a manned boat that suggests a tranquil human presence. In addition, its depiction of a thriving marine ecosystem in clear, pure waters is entirely at odds with most climate change novels that represent the progress of future urban floods. Mirroring the experience of many when dealing with the aftermath of real urban floods, when raw sewage often rises up from underground sewers, these fictions undermine the image of any future flood waters as restorative or regenerative.

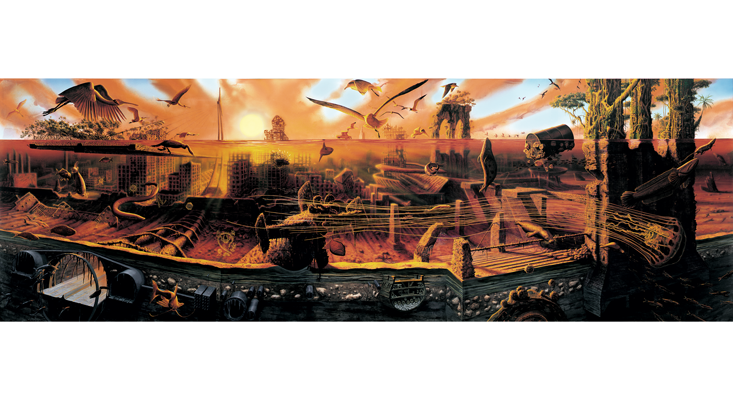

At first glance, the flood waters in Alexis Rockman’s painting Manifest Destiny (2003–4), seem to be supporting an equal abundance of life as Squint/Opera’s image of a bucolic flooded London.18,19,20 But this is not life as we know it; it is an extraordinary array of organisms made up of a mixture of recognizable flora and fauna (algae, coral, seals, lampreys, carp, an enormous jellyfish, sunfish, and lionfish underwater; and gulls, cormorants, egrets, and pelicans above) and strange new bioengineered species, including fish sprouting pustules, outsized deadly viruses (identified by the artist as HIV, West Nile, and SARS) and other bacteria-like creatures and mutant crustaceans.18 Most of the non-human life in the painting seems alien, for this is a split-level panorama of the New York district of Brooklyn in the year 5000, after global warming has not only submerged the city but transformed its climate from temperate to tropical. Despite the fact that the landscape is empty of human beings, the legacy of the latter is evident everywhere. Here, the remains of the built environment—the Brooklyn Bridge on the right, vestigial skyscrapers in the distance and, perhaps most strikingly, the city’s subterranean infrastructure of tunnels, storage vaults, sewers, and gas and water pipes—not only linger in the far distant future but have played a key role in the evolution of the organisms that now inhabit them. Scattered throughout the image are also the products of present-day accelerated capitalism that mock the hubris that characterizes our technological age—a floating oil barrel, a sunken oil tanker, stealth bomber, and submarine. Finally, Rockman also includes in his painting the remains of projects yet to be built (in 2004), most notably dykes and sea walls meant to protect the city against sea-level rises, but which, in the far distant future, have long been overwhelmed by the inexorable flood waters.

In its extraordinary attention to detail and concern with accuracy—during the process of creating the work Rockman consulted with palaeontologists, biologists, archaeologists, and architects—Manifest Destiny presents not only a dire warning to a pervasive contemporary reluctance to change the destructive course of industrial capitalism, but also a compelling image of how the human-built world will continue to influence the evolution of the environment long after humans themselves have disappeared. With its mixture of tropical and surreal flora and fauna, the intensity of its sunlight and the absence of humans, Rockman’s vision mirrors Ballard’s hallucinogenic image of a future London in The Drowned World; yet, unlike that novel, it points us back to ourselves in the here-and-now, challenging us to think more seriously and more imaginatively about the long-term effects our collective actions will have on the world to come. As such, Manifest Destiny chimes strongly with the emergence of the idea of the Anthropocene in the 2000s as defining a new epoch in geological time in which human activity, and particularly an accelerating urbanism, is as “geologic” a force as natural ones. Even though the painting transports the viewer to a barely conceivable 3,000 years into the future, it nevertheless spells out clearly the connections between our own time and this long jump forward. The painting breaks down the entrenched humanist distinction between natural and human history—in Manifest Destiny, both the future of the city and of nature are thoroughly intertwined. As such, the painting clearly flags up the need to think through those connections today and to recognize that they are already putting us on the road to the future envisaged in the painting. However, as its ironic title suggests, such a future is not inevitable; rather, Manifest Destiny invites us to consider how our own small actions are interwoven with the world and how they might be changed to co-create a more sustainable future.

Manifest Destinyalso calls into question the current tendency to combat urban inundations with more effective flood defenses, as seen in both post-Katrina New Orleans and in many towns in the U.K. affected by recent flooding. With New York’s own future-built flood defenses swallowed by the sea, the painting clearly shows the folly of such an approach in its unwillingness to make the deeper changes to both mitigate and adapt to global warming, a point that is perhaps at last being recognized in a shift toward ideas of resilience in the U.K. government’s 2016 National Flood Resilience Review.

In both literary and visual depictions of submerged urban futures, the intention is clearly to engage our imaginations in thinking through a radically different kind of future urban life. Even though the urban transformations depicted in many fictions and images of the effects of future climate change are extreme or exaggerated, they nonetheless provide intimations of what might be required for genuine human and social transformation to occur.

Paul Dobraszczyk is a researcher and writer and a teaching fellow at the Bartlett School of Architecture, London. He is the author of The Dead City: Urban Ruins and the Spectacle of Decay and Iron, Ornament and Architecture in Victorian Britain, as well as coeditor of Global Undergrounds: Exploring Cities Within.

Reprinted with permission from Future Cities: Architecture and the Imagination by Paul Dobraszczyk, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2019 by Paul Dobraszczyk. All rights reserved.

References

1. Robinson, K.S. New York 2140 Hachette Book Group, New York, NY (2017).

2. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis, Summary for Policymakers www.ipcc.ch (2014).

3. Stern, N. Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change (2006).

4. Yusoff, K. & Gabrys, J. Climate change and the imagination. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 2, 516–534 (2011).

5. Hulme, M. Why We Disagree about Climate Change: Understanding Controversy, Inactivity and Opportunity Cambridge University Press (2009).

6. Machin, A. Negotiating Climate Change: Radical Democracy and the Illusion of Consensus Zed Books, London (2013).

7. Bulkeley, H. Cities and Climate Change Routledge, London (2013).

8. Pelling, M. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation Routledge, London (2011).

9. Skilton, D. Contemplating the ruins of London: Macaulay’s New Zealander and others. Literary London: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Representation of London 2 (2004).

10. Nead, L. Victorian Babylon: People, Streets and Images in Nineteenth-century London Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (2000).

11. Withington, J. Flood Reaktion Books, London (2013).

12. Page, M. The City’s End: Two Centuries of Fantasies, Fears, and Premonitions of New York’s Destruction Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (2008).

13. Daily Mail Reporter. Our Future Underwater: Terrifying New Pictures Reveal How Britain’s Cities Could Be Devastated by Flood Water www.dailymail.co.uk (2011).

14. Azzarello, N. Architecture Under Water: Francois Ronsiaux Images Man’s Habitat Post Ice Thaw www.designboom.com 92015).

15. Meredith Bennett-Smith, M. Nickolay Lamm’s Sea Level Rise Images Depict What US Cities Could Look Like in Future Huffington Post (2013).

16. Gandy, M. The Fabric of Space The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA (2014).

17. Marcus Fairs, M. Flooded London by Squint/Opera. www.dezeen.com (2018).

18. Rockman, A. Manifest Destiny Gorney Bravin + Lee / Brooklyn Museum. Brooklyn, (2005).

19. Yablonsky, L. New York’s Watery New Grave The New York Times (2004).

20. Page, M. The City’s End Yale University Press, New Haven, CT (2010).