The mediocre universe… Depending on

how you look at it, that is either a term of derision or an

interesting, mind-warping concept. Cosmologists who are enamored of

the theory that there are many, or perhaps infinite, universes like

to look at our cosmic home and call it average, boring, run of the

mill, vanilla. They don’t do this because—like kids growing up in

the suburbs—they long for the city lights of a more exciting

cosmos. They do it because they think they have too. They do it

because there is a problem that needs to be solved and, for some,

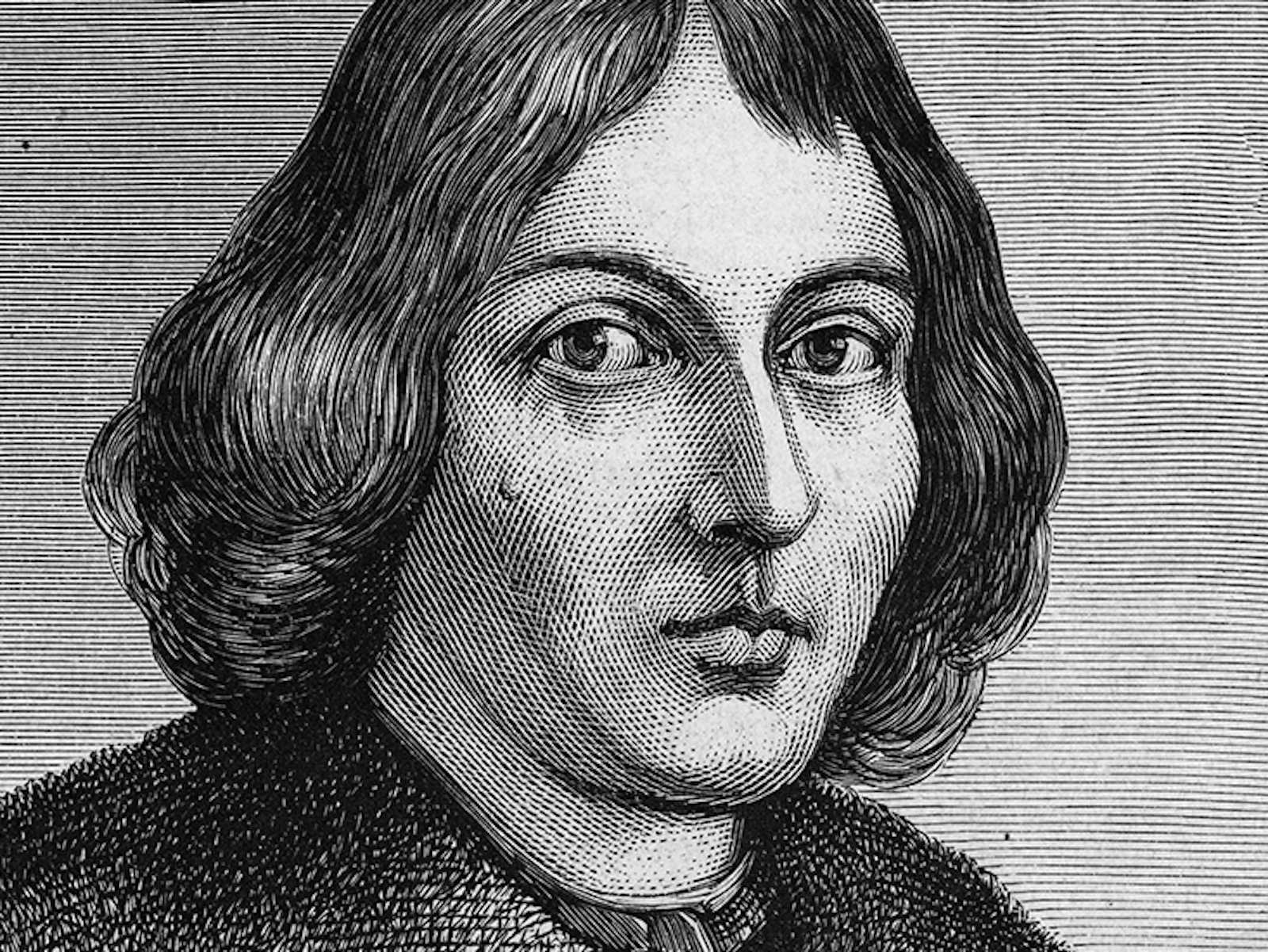

Copernicus and his principle seems the right path to solve it.

In his thoughtful article “Goodbye Copernicus, Hello Universe,” astrobiologist Caleb Scharf lays out

the foundations of so-called Copernican principle. The idea is

central not only to astronomy but to science as a whole. The

Copernican principle says that you, as an observer, are not special.

You don’t live in a special time. You don’t see things from a

special position. The power behind the Copernican principle is that

scientists try to never, ever, ever forget its admonition as they

attempt to explain the world. Relativity—with its emphasis on the

lack of any privileged frame of reference—was a triumph of the

Copernican worldview. Thus, from Copernicus’ perspective, you, and

everything about you, is mediocre.

Sorry.

Now there was a time when the universe

as a whole could be thought of as special; it was, after all, the only

one there was, by definition. The problem, however, was the universe

turned out to be a little too special.

As cosmologists poked around Big Bang

theory on ever-finer levels of detail, it soon became clear that

getting this universe, the one we happily inhabit, seemed to be more

and more unlikely. In his article, Scharf gives us the famous example

carbon-12 and its special resonances. If this minor detail of nuclear

physics were just a wee bit different, our existence would never be

possible. It’s as if nuclear physics were fine-tuned to allow life.

But this issue of fine-tuning goes way beyond carbon nuclei; it

infects many aspects of cosmological physics.

Change almost anything associated with

the fundamental laws of physics by one part in a zillion and you end

up with a sterile universe where life could never have formed. Not

only that, but make tiny changes in even the initial conditions of

the Big Bang and you end up with a sterile universe. Cosmologically

speaking, it’s like we won every lottery every imaginable. From

that vantage point we are special—crazy special.

Fine-tuning sticks in the craw of most

physicists, and rightfully so. It’s that old Copernican principle

again. What set the laws and the initial conditions for the universe

to be “just so,” just so we could be here? It smells too much

like intelligent design. The whole point of science has been to find

natural, rational reasons for why the world looks like it does.

“Because a miracle happened,” just doesn’t cut it.

Even more important, as of yet there is not one single, itty-bitty smackeral of evidence that even one other universe exists.

In response to the dilemma of

fine-tuning, some cosmologists turned to the multiverse. Actually the

history works a bit the other way round. Various theories

cosmologists and physicists were already pursuing—ideas like

inflation and string theory—seemed to point to multiple universes.

Given the sticky wicket that fine-tuning already represented, these

scientists were happy to take the beloved 10-dimensional strings and

jump on board.

The great thing about multiverses is

they provide a natural and Copernicus-friendly answer to the problem

of fine-tuning. Sure, our universe looks fine-tuned, but since there

are so many other universes out there, we can use that information to

actually tell us something about their properties. Given the

Copernican principle, it must be that the seemingly fine-tuned

conditions in our universe are actually average properties across the

multiverse. We must be mediocre, right? That means that if you could

look around the multiverse, you might find a universe with very

different values than ours for the fundamental constants of physics,

but on average the values you will find will be the ones we have

here. End of story.

There is a compelling momentum to the

argument when you hear it run that way. There is, however, a small

problem. Well, maybe it’s not a small problem, because the problem

is really a very big bet these cosmologists are taking. The

multiverse is a wildly extreme extrapolation of what constitutes

reality. Adding an almost infinite number of possible universes to

your theory of reality is no small move.

Even more important, as of yet there is

not one single, itty-bitty smackeral of evidence that even one other

universe exists. Worse still, there are some who would say it’s

been precisely the shortcomings of ideas like string theory that led

them to become multiverse-friendly. Not so long ago it became clear

that string theory was not leading to a single prediction for this

single universe we inhabit. Instead it predicted 10500 possible

universes. For some folks, this was not a good thing. It seemed

string theory went from a “theory of everything” into a theory of

nothing. Advocates stayed true however and proclaimed that string

theory had in a sense, discovered the multiverse. (Inflationary cosmology was also discovering the multiverse in its own way.)

Finding evidence of a multiverse would,

of course, represent one of the greatest triumphs of science in

history. It is a very cool idea and is worth pursuing. In the

meantime, however, we need to be mindful of the metaphysics it brings

with it. For that reason, the heavy investment in the multiverse

may be over-enthusiastic. The multiverse meme

seems to be everywhere these days, and one question to ask is how

long can the idea be supported without data. Recall that relativity was confirmed after just a few years. The first evidence for the expanding universe, as predicted by general relativity, also came

just a few years after theorists proposed it. String theory, in

contrast, has been around for 30 years now, and has no physical

evidence to support it.

There are likely other ways to solve

the fine-tuning quandary that don’t require creating an infinite

number of potentially unobservable universes. Some of these may

require changing the way we look at time, as Lee Smolin has suggested. Or perhaps these solutions will include a deeper

understanding of the limits of the Copernican principle. Perhaps

there is a natural, rational reason why we, or at least our universe,

really is unique in its one-time history.

Now that wouldn’t that be special.

Adam Frank, a professor of physics and

astronomy at the University of Rochester, is the author of About Time: Cosmology and Culture at the Twilight of the Big Bang and a

co-founder of NPR’s “13.7 Cosmos and Culture” blog.