The T-shirts and posters are common: an image of a galaxy, an arrow pointing to a spot in that galaxy, and a sign reading “You are here.”

But it’s all a big lie. That’s not the Milky Way, and we are not there. We have no images of our galactic home from the outside for a simple reason: We cannot travel that far. But the image isn’t wholly wrong (so long as it shows the galaxy with spiral arms, which not all versions do). We do live in a spiral galaxy, and our sun orbits the center of that galaxy about one-third of the way out.

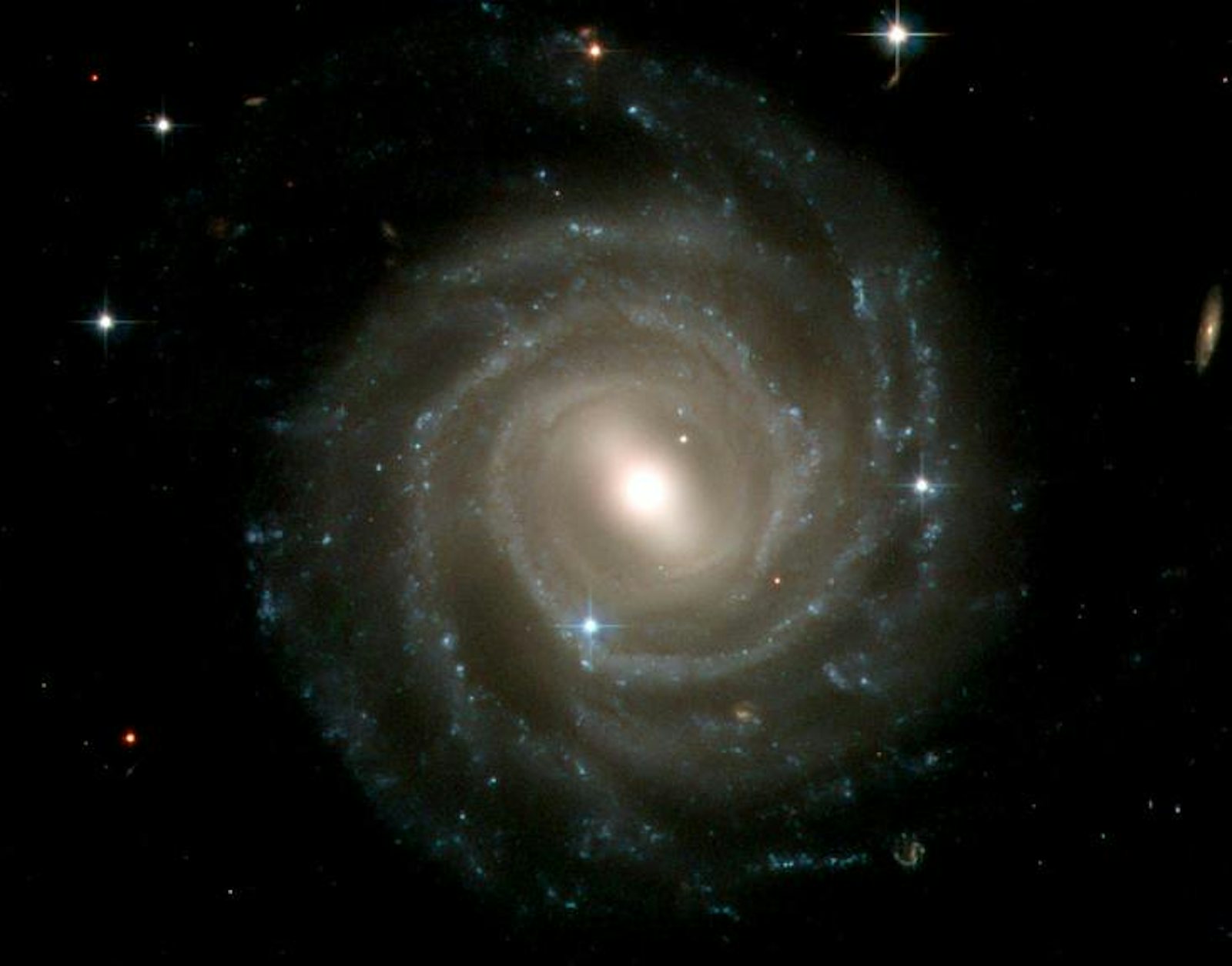

With blue-tinged arms curving around a bright center, prominent dark streaks, and puffy-looking clouds of gas, spiral galaxies are some of the most beautiful objects in the universe. And there are lots of them: More than 60 percent of large galaxies are spirals.

If you’re one of the increasingly few lucky people to have seen the streak of light that constitutes what we can see of the Milky Way, you’ve realized it looks nothing like the pictures of spiral galaxies. So how do we know that our galaxy is a spiral? How can we place the Solar System inside this galaxy if we can’t see the whole Milky Way?

As you might expect, it’s not easy. Astronomers have actively debated—with reasonable evidence to back up various assertions—whether the Milky Way has four or six arms, how many stars the galaxy has, and how its dark matter (the invisible material making up about 80 percent of the mass of the galaxy) is distributed. Just last week, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched a new space telescope that will peer all around the galaxy and help refine our understanding of it—and make ever more accurate “you are here” maps for your wall.

The ancients knew of the Milky Way and even had a similar term for it: “Galaxy” shares the same Greek root as “lactose,” the sugar found in milk. (If we say “Milky Way galaxy,” we’re basically saying “Milky Way milky way,” much like how “Sahara Desert” is utterly redundant.) Galileo turned his telescope on that blur and found it was full of stars too faint to be seen with the naked eye. In the early 20th century, Jacobus Kapteyn and Harlow Shapley independently estimated the shape and size of the galaxy by measuring the distances to individual stars and connecting those dots to trace out the galaxy’s bigger structures. Both of them got the size wrong (in opposite ways!), but Shapley determined the basic shape fairly well, including the location of the galactic center.

The reason the Milky Way looks like a streak is because many of its stars—including the sun and everything visible to the naked eye—are concentrated in a thin disk. (The galaxy is not perfectly flat, which is why you see stars outside of the streak, but its thickness is very low compared to its width.) When you look at the milky streak, you’re seeing the high density of stars in the disk.

But not all stars are created equal. We see spiral arms in other galaxies because they are places where hot, young, blue-colored stars gather. These stars are much brighter than their more numerous, cooler, more reddish cousins, which leads to an optical illusion: We see spiral galaxies as bright arms with darker spaces in between, even though the density of stars in the spiral arms is only about 5 percent greater than the density of stars than the rest of the disk. The arms are also home to hydrogen plasma, another sign that things are generally hotter in those parts of the galaxy.

That’s how astronomers can find the Milky Way’s spiral arms: Look for populations of hot, young stars and clouds of hydrogen plasma, measure the distances to them, and use that data to trace the spiral arms. It’s a tricky observation, requiring astronomers to point their telescopes through the thickest parts of the galactic disk and discern stars that appear to be side-by-side but might be tens of thousands of light-years away from each other. Much of the gas and dust in the galaxy is opaque to visible light, but radio and infrared telescopes can successfully penetrate the clouds.

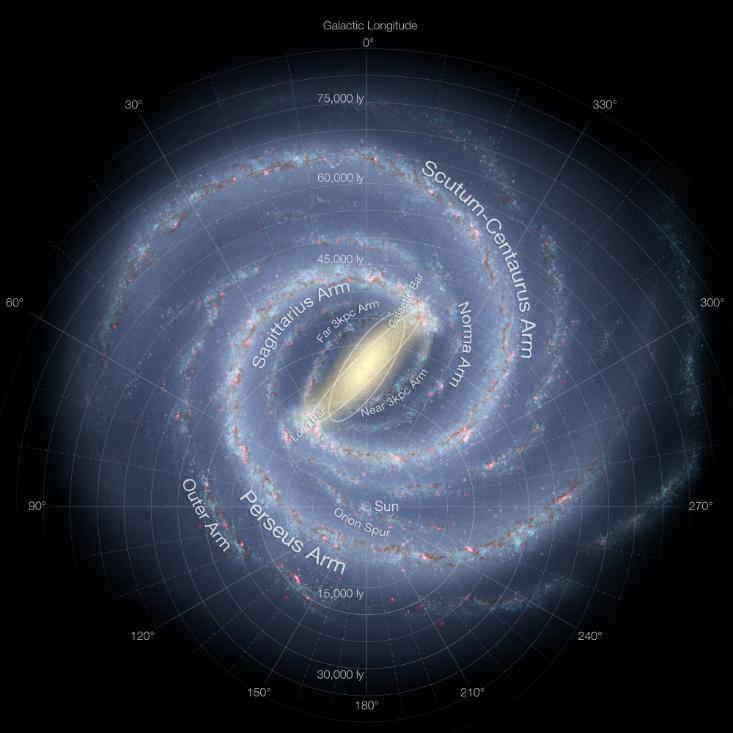

As a result, we have a fairly good idea of what the Milky Way looks like, though there are continuing refinements to that picture. We inhabit a galaxy with four major spiral arms (though two are more substantial than the others) and a number of smaller arm fragments called “spurs.” Our Solar System is in a region known as the Orion spur, likely the remnants of an earlier arm that has now faded. And that’s a good thing: The intense ultraviolet light from blue stars might make life in the major spiral arms problematic. Another region, the Norma arm, is named for my grandmother. (Not really.)

The major arms of the galaxy join a long peanut shell-shaped structure at the center of the galaxy called a bar. (About one-third of spiral galaxies have bars; see the image that started this post for a good example.) At the middle of the bar is a squashed spherical grouping of stars known as the bulge; deep inside that resides the central black hole, a nucleus about 4 million times the mass of the sun.

Beyond the spiral arms we see a halo, an approximately spherical region, nearly 10 times larger than the disk, scattered with old stars. The halo is also home to most of the galaxy’s dark matter, which provides the gravity to hold everything together. In an effort to draw the structure of the galaxy in even greater detail, the ESA launched a new space observatory called Gaia last Thursday. This probe consists of two visible-light telescopes designed to map and measure distances to more than a billion stars. The result will be a better understanding of the three-dimensional structure of the Milky Way, including higher-precision knowledge of the spiral arms and the shape of the central bar. Gaia should also reveal information about the distribution of dark matter deep into the messy middle part of the galaxy, which is currently unknown.

Gaia is just the latest of many projects to map our galaxy. It joins searches for our sun’s nursery, Earth-like planets, surveys of stellar graveyards, measurements of the Milky Way’s rotation, and numerous other missions. Like cartographers in the past who strove to map the entire planet, astronomers in the 21st century are making an atlas of the Milky Way with the ultimate goal of better understanding our galactic home.

Matthew Francis is a physicist, science writer, public speaker, educator, and frequent wearer of jaunty hats. He’s currently writing a book on cosmology with the working title Back Roads, Dark Skies: A Cosmological Journey.

Lead image: ESA/Hubble & NASA