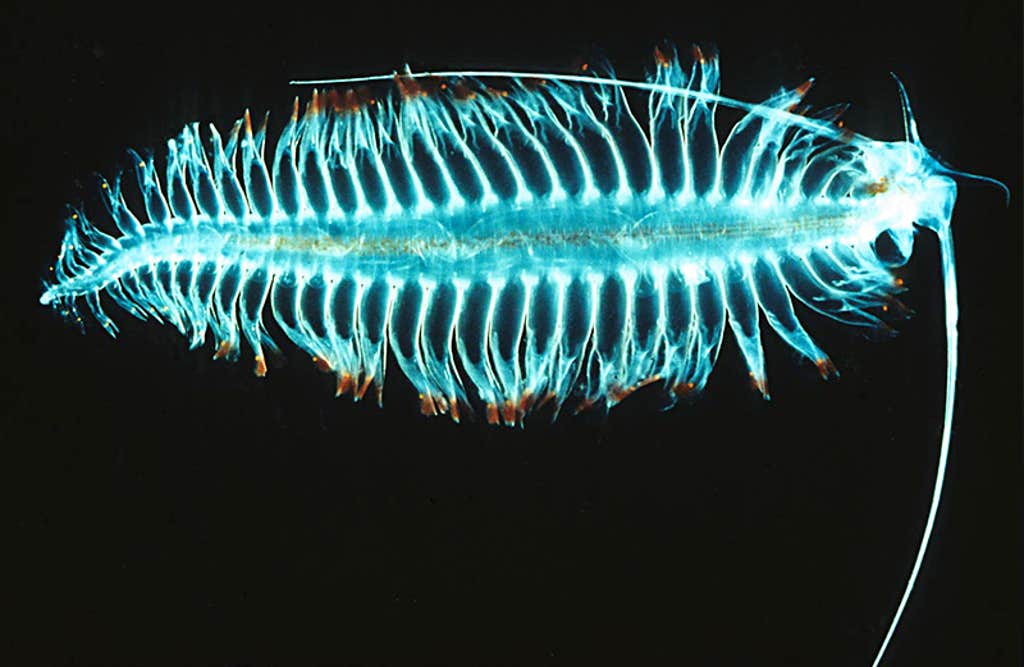

The gossamer worm is a tiny feathery creature that lives 4,000 feet below the surface of the sea, in the blackest depths of the deep ocean. Recently, scientists found evidence that to locate its prey— larval fish and transparent arrow worms—the creature uses a pair of antenna-like tentacles to probe the water for whiffs of ammonia and sugars. The finding hints at how a creature that spends its entire life in a dark, seemingly featureless environment might find enough food to survive.

An estimated one-third to two-thirds of species in the ocean remain unknown to science. Many of them are delicate gelatinous creatures like the gossamer worm, which are challenging to collect and do not preserve well. Until recently, even to sample a bit of genetic material from such creatures, scientists had to bring them to the surface, a process that can alter gene expression—never mind physical features—due to dramatic changes in temperature and pressure the creatures experience on the way up.

But now, a new method of analysis is allowing scientists to do this work deep beneath the surface of the sea. Described in a recent paper published in Science Advances, the method features a pair of 3-D imaging systems as well as an origami-inspired collecting device with built-in tissue sampling and preservation. The researchers say that together, these technologies will enhance our understanding of how marine creatures look and behave in their natural environment. They could also accelerate the pace of new species discovery and description in the ocean.

The Science Advances paper tells the story of a five-year research odyssey centered on two cruises. The first cruise took place in October 2019 off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii, and focused on working out the technical kinks. The second cruise, in August 2021, off the coast of San Diego, entailed seven different dives with a submersible during which scientists interacted with more than five dozen life forms, including the gossamer worm, amphipods, relatives of jellyfish, comb jellies, echinoderms, single-celled protozoans with mineral skeletons called radiolarians, tunicates, mollusks, and sponges.

“It felt like you were a space explorer in the future encountering some alien species, and just like a sci-fi novel every tool you ever could imagine was available to you,” says Brennan Phillips, an oceanographic engineer at the University of Rhode Island and one of the leaders of the study.

When an interesting looking animal came into view, the researchers would first use a laser scanning system called DeepPIV to create an intricate three-dimensional image, akin to a CT scan, of the creature and to measure the currents of water it created as it moved. Then they would train the red glow of a lightfield camera called EyeRIS—which contains an array of microlenses similar to those found in an insect’s compound eye—on their specimen. The system can take precise measurements of an animal’s body in three dimensions in a matter of seconds.

Finally, they would enclose the creature in a kind of underwater fishbowl called the RAD-2. The 12-sided shape is made of stainless steel, anodized aluminum, and a durable kind of plastic, and it folds up into a beach ball-sized chamber so that an animal is simultaneously contained and yet swimming freely in an environment nearly identical to its natural home.

The RAD-2 contains a device that collects and pulverizes tissue samples from the organisms and sucks these samples through a hole where the samples are hit with preservative and deposited on one of 14 filters for later analysis. The investigation of the gossamer worm’s sensory tentacles was possible because the worm is so small that, by chance, it happened to get sucked through the hole intact.

One major future goal is to equip their new tool with technology that can swab animals for DNA and take minimally invasive biopsies without sacrificing the creatures. The aim is to “be able to give floating animals in the deep sea something akin to a doctor’s checkup,” says David Gruber, a marine biologist at the City University of New York and a leader of the study. “We’re working further and further to get more and more gentle.” It’s no small matter to get such a subtle instrument to withstand the extreme conditions of the deep sea. But Gruber estimates that, with some more focused tinkering, such an instrument could become a reality within a few years’ time.

On the San Diego cruise, the team mostly interacted with species that are already part of the scientific record. But in the future, they hope to take their research toys to less known parts of the ocean. They say the new approach they have engineered is capable of capturing sufficient information about the appearance, behavior, and genetics of unknown creatures to describe new species without collecting the physical specimens that are at the center of conventional taxonomy.

Somewhere between New Caledonia and Vanuatu swims an unknown deep sea creature, a second or third cousin of the gossamer worm, whose form could soon become fully known to science without it ever leaving its watery home. ![]()

Lead image: Dabarti CGI / Shutterstock