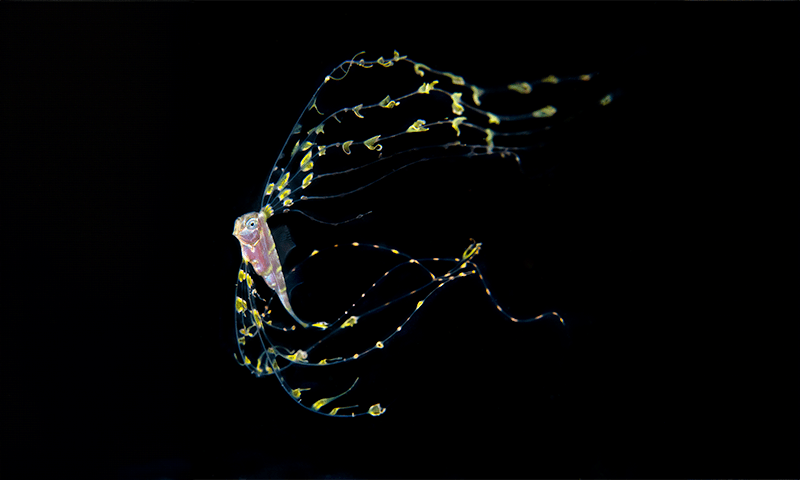

Just as many staid adults were once rebellious teenagers in interesting clothing, many marine fish species enter life as flamboyant larvae that bear little resemblance to their mature forms. The juvenile scalloped ribbonfish pictured here, for example, eventually loses its flowing fin rays and grows into a teardrop-shaped adult that can reach over a meter long.

Or take the ribbon sawtail fish, which begins life with charmingly dopey eye stalks a quarter of the length of its body, and later becomes a svelte-eyed monster with an underbite full of snaggled needle teeth. Still others have guts that dangle like a second tail or offer dazzling color displays that they shed with time.

The differences between larvae and adults can be so significant that, through the 19th and 20th centuries, many larvae were misclassified as separate species or genera from the adults they would become. Scientists believe that these body changes have to do with diverging evolutionary pressures on larvae and adults.

The food-rich zone near the ocean’s surface is, after all, a very dangerous place to be tiny. The scalloped ribbonfish’s resemblance to a jellyfish with a nasty sting may be an effective deterrent to potential predators. And the ribbon sawtail fish’s eyestalks may do double duty by both easing its own efforts to find prey, and allowing it to search the water with minimal body movement that could attract creatures hoping to gulp it down.

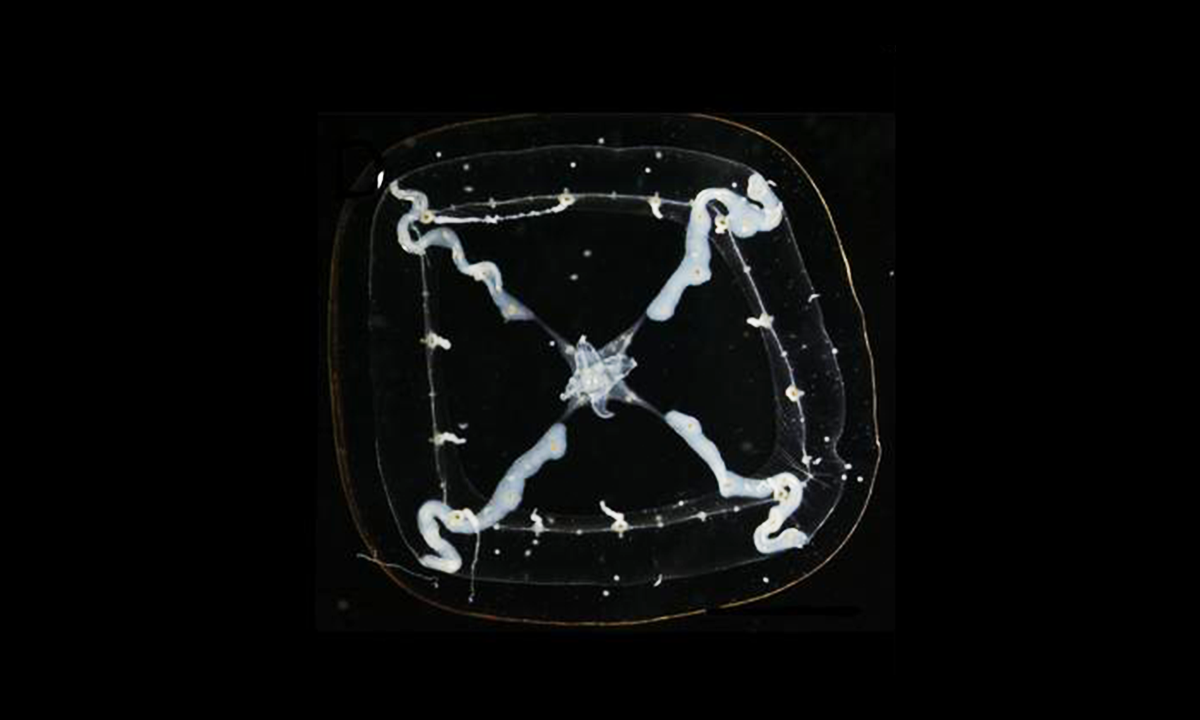

Larval marine fish and invertebrates across the globe also participate en masse in defensive vertical migration. During the day, they descend to deeper water to avoid predators that hunt by eyesight. But by night, under cover of darkness, they rise to the surface to feed. The U.S. Navy first discovered this phenomenon in the ocean during World War II, when pings from sonar revealed a deep layer of interference that disappeared at night, like some kind of phantom web.

The ocean’s surface is a very dangerous place to be tiny.

But some knowledge of larvae’s morphological adaptations is more current. The cone-shaped trawl nets that scientists have long used to collect zooplankton, including larval fish, can mangle and break off the creatures’ ostentatious parts. And the fixatives used to preserve specimens drain their color. Recently though, the emerging practice of blackwater photography has brought these animals into clearer focus. Blackwater divers enter the water in the dead of night with bright lights and macro lenses. The resulting images of tiny creatures going about their lives in full color reveal much more about their bodies and behaviors than do their bleached, partial corpses.

Hitchhiking, for example, is ubiquitous. Magnus Lundgren, the Swedish underwater photographer who captured this scalloped ribbonfish, has also photographed nautiluses riding atop jellyfish and fish swimming among their tentacles, as well as fish and octopuses traveling inside or atop floating tunicates. What these creatures accomplish by sticking together isn’t clear. But perhaps with enough teamwork of their own, scientists and blackwater divers will illuminate answers as spectacular as the creatures themselves. ![]()

Magnus Lundgren is a decades-long, Swedish-born professional photographer who has been taking images for as long as he can remember. He is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading underwater photographers and is honored to work in the field of conservation photography. For him, conservation is the ultimate motivation.

This story originally appeared in bioGraphic, an independent magazine about nature and regeneration powered by the California Academy of Sciences.