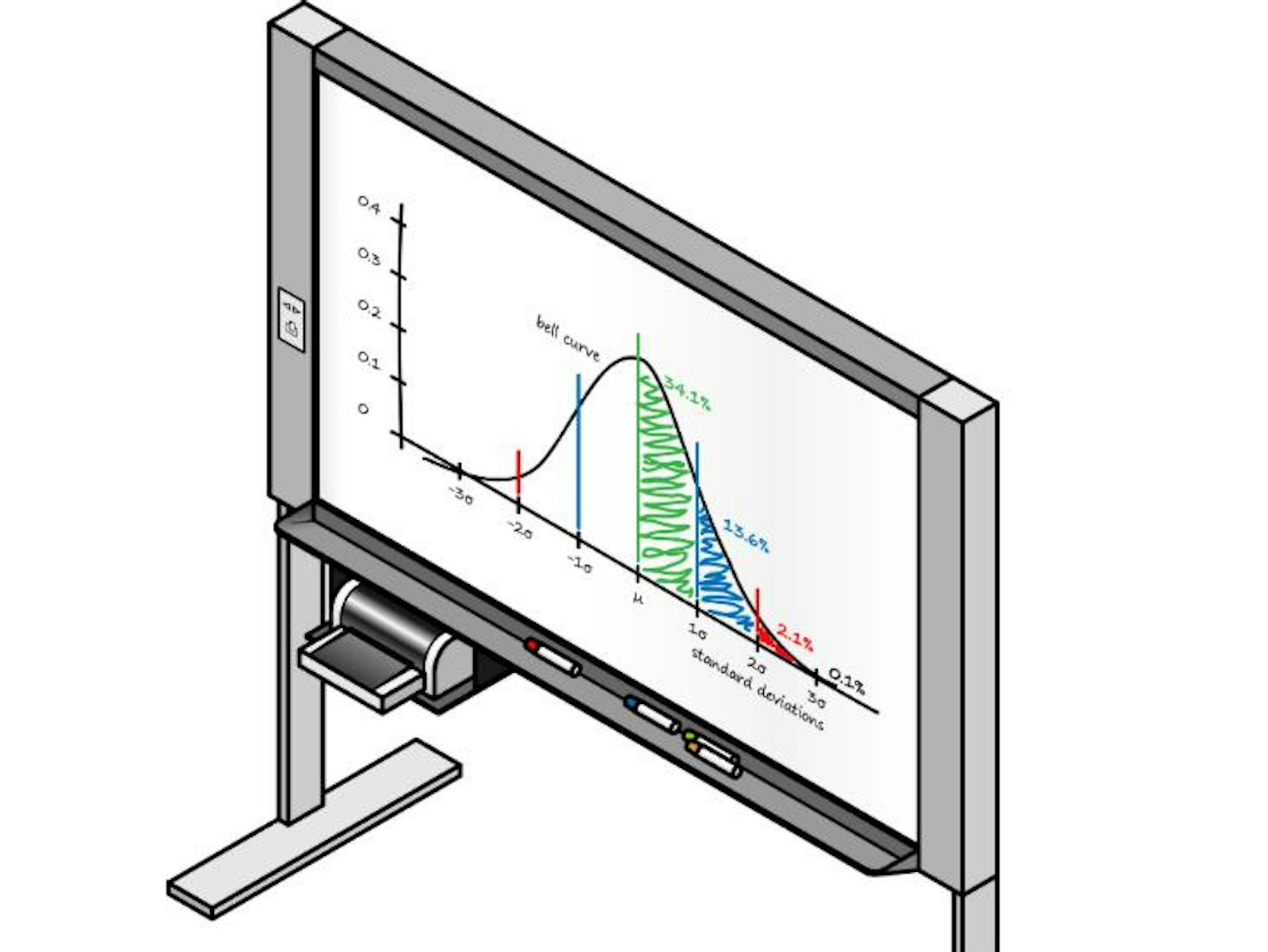

It’s well-known that statistics is a deceptively difficult topic to understand—at least, it’s well-known among people who’ve had some training about those deceptive difficulties. One concept, though, that seems to penetrate the barriers to statistical understanding is the normal distribution, the standard bell curve. Even if people don’t have the mathematical language to describe it, many have an intuitive handle on normal distributions—that, for instance, most people are near average in height, while some are short or tall, and a few are very short or very tall. Humans seem to encounter the bell curve often enough that even our statistically challenged brains can get a decent feel for it. Which may only make things harder when we deal with systems that are quite far from normal.

Tech investor Paul Graham wrote an essay last year illustrating just how far his line of work is from the world of normal distributions. Graham co-founded an influential company called Y Combinator that invests in and helps out startup tech companies looking to make really cool things and, in the process, tons of money. When the investments go just right, they don’t just pay off in thousands or even millions of dollars. Out of around 500 companies that Y Combinator’s invested in, all of them run by smart, ambitious founders, just two—Dropbox and Airbnb—represented a full three-quarters of the value of their entire portfolio, which totaled about $10 billion.

Clearly, the distribution of values of startup tech companies is very far from normal, with the smash successes generating 10,000x return on investment, and many others basically disappearing, at least in terms of the bottom line. (For another look into the psychology of giant pay-offs, see the related Nautilus article, “Why We Keep Playing the Lottery.”) What’s more, Graham says, there doesn’t seem to be any way to predict which companies will be the unlikely few to explode: They have to be good ideas that seem bad, their appeal to investors means nothing, and they won’t emerge as winners for years. Even for an insider with a prime view of the venture capital world and a good feel for statistics, the drastic range of outcomes is disorienting:

In startups, the big winners are big to a degree that violates our expectations about variation. I don’t know whether these expectations are innate or learned, but whatever the cause, we are just not prepared for the 1000x variation in outcomes that one finds in startup investing…I haven’t really assimilated that fact, partly because it’s so counterintuitive…To succeed in a domain that violates your intuitions, you need to be able to turn them off the way a pilot does when flying through clouds. [2] You need to do what you know intellectually to be right, even though it feels wrong.

I hadn’t previously heard of spatial disorientation, the challenge to pilots that Graham alludes to. When flying in bad weather, when there is no clear view of a horizon, It is apparently quite easy to lose track of something as basic as which way is up. For pilots who are unprepared, flying in conditions like that can be an express elevator into the ground, and then below it; Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper met their ends in a plane crash just a few minutes after an inexperienced pilot took off in bad conditions and presumably became spatially disoriented. The only way to reliably fight the effect is to learn to depend on the plane’s instrumentation and utterly ignore the messages you get from your vestibular system, which provides a good sense of balance and motion when we’re planted on terra firma. It’s a great metaphor for the challenge of understanding freak events. As venture capitalist, you’re probably better off shutting up the regular rational thoughts, just like the pilot in a storm ignoring the messages from deep within their ears. But that feeling can be hard to shut down, says Graham:

We’ll probably never be able to bring ourselves to take risks proportionate to the returns in this business. The best we can hope for is that when we interview a group and find ourselves thinking “they seem like good founders, but what are investors going to think of this crazy idea?” we’ll continue to be able to say, “who cares what investors think?”

Thanks to Eric Nguyen for the pointer to Graham’s essay.