January 1996 was, in most respects, a month like any other in Jefferson County, Colorado, the “Gateway to the Rocky Mountains.”* But one thing distinguished that particular month in that particular county in Colorado: an outbreak of salmonellosis among children, most of whom were under 13 years of age. The Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment found a type of the bacteria called Salmonella enteritidis in at least 39 confirmed cases, and there may have been over 300 more children infected.

Salmonellosis is, itself, not a particularly rare infection in the United States. According to the CDC, it is seen in 42,000 people each year, mostly children. And because salmonellosis often resolves itself in most patients, milder cases tend not to be diagnosed or reported, suggesting that the true number of infections each year may be more than 1.2 million.

The symptoms of Salmonella infection are also not very extraordinary. Beginning 12 hours to three days after infection, patients experience abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and fevers. The body’s immune system usually manages to fight off the infection after several days. The source of Salmonella infections is just as unremarkable as their manifestation. Since it’s associated with fecal material, it is often traced to contaminated or undercooked foods like meat, poultry, eggs, and milk.

But the January 1996 Salmonella outbreak in Jefferson County, Colorado, was traced to an unlikely source: the Denver Zoo. Jefferson County Health Department officials showed that the only common link among the infected patients was that they had visited the zoo. That’s when the CDC became involved.

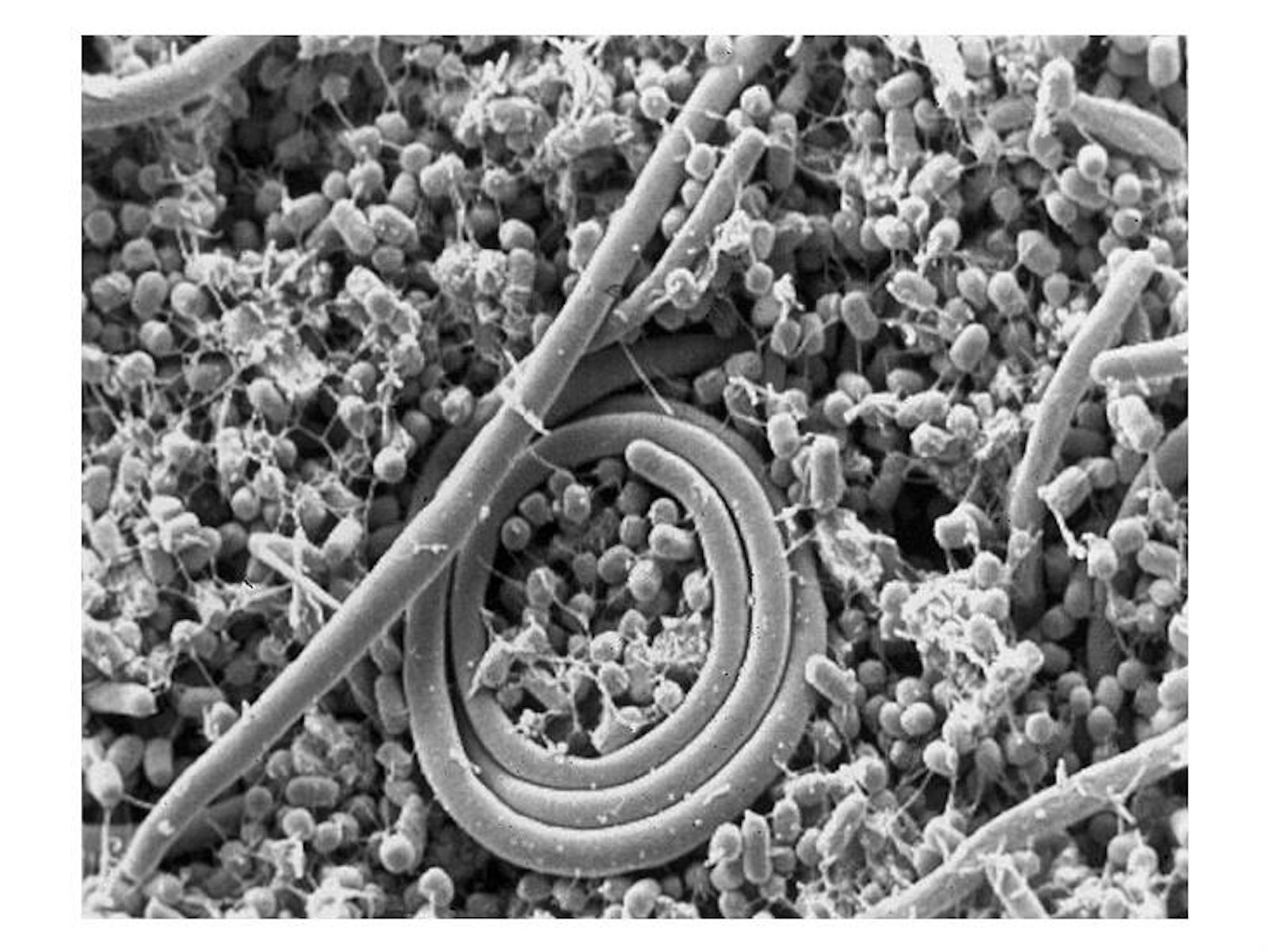

Using a statistical test known as logistic regression, CDC researchers verified that zoo concessions, an obvious suspect, were not the source of the infection. Neither was any other zoo exhibit outside of the reptile house. When tests for Salmonella enteritidis turned up positive in fecal samples of one of the four Komodo dragons, but negative among the keepers and veterinarians who handled them, it seemed as if the culprit had been found. The dragons’ mother, located at another zoo, did not have the infection, and neither did any other reptile in the reptile house. (Some other reptiles had other varieties of Salmonella, but not the one implicated in this outbreak.) The researchers even tested the intestinal tracts of the frozen rats that were used to feed the Komodo dragons and found nothing. Just to be sure, the CDC officials also tested some preserved reptile skins that were on display in the exhibit, but they found nothing there either. The one infected Komodo dragon, it seemed, was patient zero.

Despite their evolutionary remove from humans, reptiles are actually known vectors for salmonella infection in the United States. For this reason, the CDC recommends that households with young children not have pet reptiles, such as snakes or turtles. Still, catching this bacterial infection from a Komodo dragon in a zoo was literally unheard of: Some 95% of the 174 Association of Zoos and Aquariums-accredited zoos in North America exhibit reptiles, and this was the first report of salmonellosis in kids after visiting those exhibits.

So how did the infection jump from a Komodo dragon to a bunch of children? The Health Department verified that none of the infected patients had touched or petted any of the dragons—something that would be unusual for a zoo in the first place, and a spectacularly bad idea for a species whose venomous bite can do some serious damage, killing deer and even water buffalo. An investigation showed that the method of transmission was even more surprising than the fact that it happened.

The enclosure itself consisted of a pen made of two-foot-high wooden barriers within the reptile house. The floor was covered with mulch, and that mulch wasn’t replaced at all during the time in which the dragons were housed there. The CDC researchers described how it was this environment that probably led to the outbreak:

The Komodo dragons, one of which was infected with [Salmonella] enteritidis, stood in fecally contaminated mulch and frequently placed their front paws on the tops of the barriers. The visitors frequently touched these same barriers and most likely became infected when they later placed their contaminated hands in their mouths or cross-contaminated something they were eating.

Given the carefully controlled temperature and humidity of the reptile house, the bacteria could have survived on exposed surfaces like the wooden railings for up to 10 months, meaning that patients could have become infected long after the infected dragon was relocated or became healthy.

Of course, not all visitors to the Komodo dragon exhibit, even among those who touched the barrier, became infected. Careful zoo visitors could prevent this unlikely infection with the most likely of solutions: washing their hands.

* Correction, August 15, 2013: The post originally located Denver in Jefferson County. It is not.

Jason G. Goldman received his Ph.D. in developmental psychology at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles and writes a blog called The Thoughtful Animal, hosted at Scientific American. His doctoral research focused on the evolution and architecture of the mind, and how different early experiences might affect innate knowledge systems.