Reflections on Sam Shepard’s time at the Santa Fe Institute

I was first introduced to Sam by our mutual friend Valerie Plame Wilson. Sam had played Valerie’s father in the cinematic adaptation of her book, Fair Game. On the phone inviting Sam to SFI his first question to me was whether there would be sufficient desk space for a typewriter. I assured him that this would not be a problem.

We met a few months later in Santa Fe and discussed our favorite pens and notebooks. I have a weakness for large fountain pens. Sam noted that they leak and favored ball pens and pencils which he kept in his pocket to record thoughts impromptu on scraps of paper in diners. His favorite diner in Santa Fe was Harry’s Roadhouse, where he would sit at the bar and make his observations. From a diner’s point of view Sam was a naturalist of the twilight zones of Americana.

Sam was largely interested in the poetry of scientific expression.

Sam was a Miller Scholar at SFI, a position for artists and scholars supported by the endlessly surprising investor Bill Miller, who is somewhat uniquely committed to rigorous mavericks, outsiders, and in his wording, “orthogonals.” All are selected on the basis of their creative excellence ignoring the prisons of genres, fields, and disciplines.

Sam was drawn to SFI in part through Cormac McCarthy as they are friends of long standing. I think of them as kindred spirits—both aesthetes rendered lapidary and visionary by the unforgiving photons of the high desert. I wish I could say the same for the rest of us.

Sam, Cormac, Jessica Flack (my wife and collaborator at SFI), Tim Taylor (my complexity aide-de-camp) and I often discussed the merits and visions of Nabokov, Hamsun, Melville, and Beckett. Sam loved Roberto Bolano, whom Cormac viewed, as he does all contemporary writers, as too close for equitable analysis.

Cormac is deeply interested in and influenced by science and mathematics—philosophically speaking he is a scientist. Sam was largely interested in the poetry of scientific expression.

Sam shared with Cormac a deep love of American landscape, a geological affinity for the earth and a profound respect for non-human nature: of whales, horses, and wolves. Like Cormac, Sam was a member of the congregation of Melville, the parish of Beckett, and had a strong genealogical identification with Ireland, Irish culture, and Irish lyricism.

While at SFI Sam became interested in our work on the history, structure, and potential of language. We would share short passages from Bruno Schulz that manage, through some mental condensation, to distill into words an elemental insight, as in: “An event may be small and insignificant in its origin, and yet, when drawn close to one’s eye, it may open in its center an infinite and radiant perspective because a higher order of being is trying to express itself in it and irradiates it violently” (excerpted from the Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass). This is exactly what we do in science and is a perspective that promotes common cause among scientist and artist.

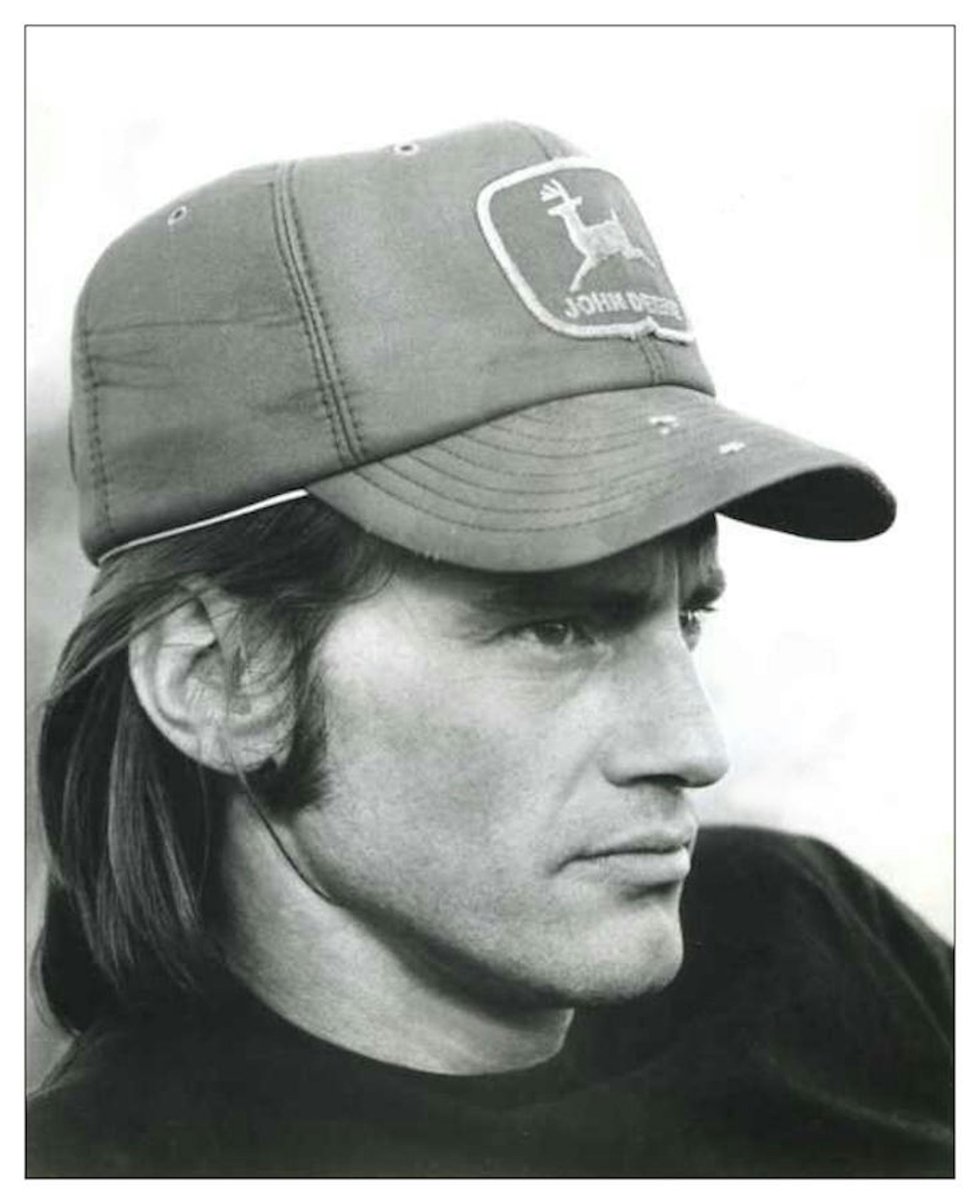

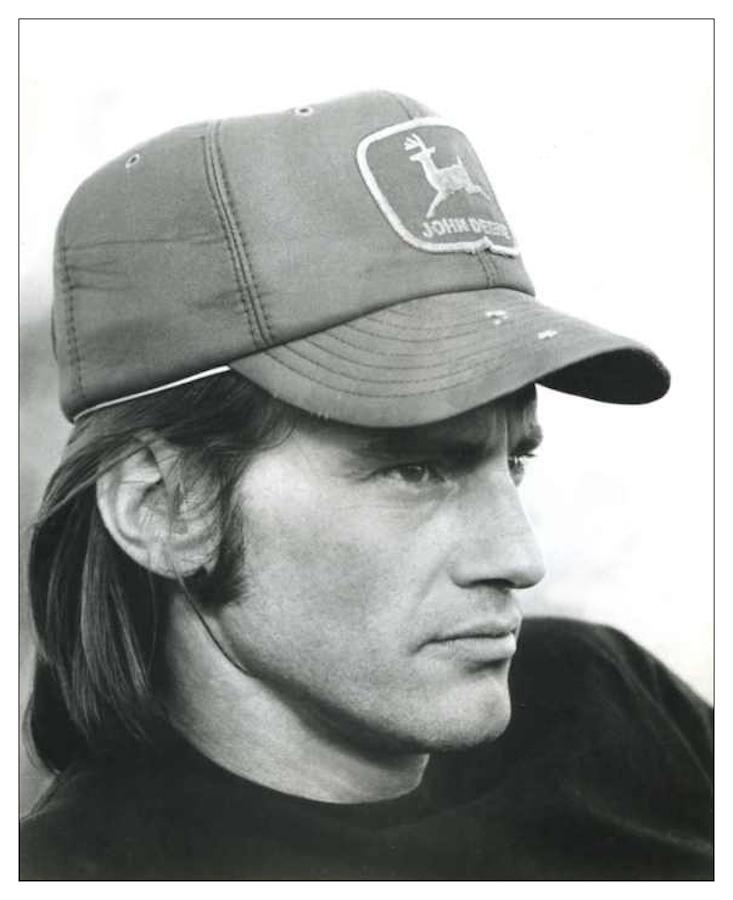

Some of my last conversations with Sam were about Carl Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. I could not decide whom Sam loved more, Renée Falconetti or Antonin Artaud. He was fascinated by the expressive power of silent film and the possibility of resting one’s gaze on a face for a very long time—a countenance primordial, sensitive, and invulnerable.

I guess that is how I and many others looked at Sam.

David Krakauer is President of the Santa Fe Institute and William H. Miller Professor of Complex Systems.

Sam Shepard is survived by his three children, Jesse Mojo, Hannah Jane, and Samuel Walker Shepard, as well as his sisters, Sandy and Roxanne Rogers.