Ellen Swallow Richards was not going to be intimidated by a room full of health experts and officials. Children were dying and their parents, Boston’s taxpayers, and city officials were to blame. The tiny, square-chinned woman thought nothing of climbing over boulders in petticoats, collecting thousands of water samples by horseback, or exploring mines on her honeymoon. So when she took the podium at the 1896 meeting of the American Public Health Association, she wasted no time in laying out her evidence.

More than 5,000 cases of illness could be attributed to the illegal conditions in Boston’s public schools, she said. Buildings lacked ventilation. Sewer pipes were still open. Toilets were filthy. Some 41 percent of the floors had never been washed. Only 27 of the city’s 168 schools had fire escapes that worked. Fully half of Boston’s schoolhouses were “deleterious to health.” The public and parents should be charged with “the murder of some 200 children per year,” Richards declared, their deaths entirely preventable from environmental hazards.

The strident, accusatory tone of Richards’ speech was remarkable, given how tactful she had been in the first two decades of her career. That tact had been a coping strategy, characteristic of a pragmatic feminism. Richards had been the first woman admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the university’s first woman instructor. To blend in, she made a conscious effort to appear as unthreatening and feminine as she possibly could to her male colleagues. She even mended their clothes when they asked.

But in 1896, halfway through her career, she threw tact out the window. Now was the time for action. She had surveyed the water supply of 80 percent of Massachusetts’ population, tracing contamination and making the case for the state’s first water quality standards. Her lab at MIT was testing ingredients for adulteration and exposing food fraud. She found mahogany dust in cinnamon. Arsenic in wallpaper. Working outside the lab, she had written the United States Department of Agriculture’s first nutrition pamphlets and had made an ambitious attempt to reform the American diet, rolling out the first major school lunch program in the country, as well as experimental kitchens in New England to feed people the cheapest, most nutritious meals that science could devise. She looked forward to the day when poisoning students with bad air would be considered a crime.

Richards was more than one of America’s first and most vocal activists, a consumer advocate before the term existed. She was driven by the principle of ecology, a new field of study at the time, that focused on the interactions of plants and animals, and how those interactions sustained the health and survival of species. Richards, though, went further. She introduced the term ecology, coined by German biologist Ernst Haeckel, to the American public, and defined it as “the science of normal lives.”

Ellen had no ambitions to be Helen of Troy. She intended to be the Trojan horse.

This was remarkable because science at the time was considered the province of men. And men came to define ecology very differently from Richards—they saw it, primarily, as concerned with the study of relationships in nature. People observed from the sidelines. Yet Richards wanted to include people and the urban environment in her definition of ecology. She wanted to apply scientific principles to understand and regulate living conditions—to improve the food people ate, the air they breathed, the water they drank.

Before Rachel Carson was born, Richards wrote and lectured that a direct link could be drawn between the well-being of humans and the safety and cleanliness of the environment in which they lived. At the turn of the 20th century, as if she was anticipating many of the discussions taking place today in the age of the Anthropocene, Richards said, “The quality of life depends on the ability of society to teach its members how to live in harmony with their environment, defined first as the family, then with the community, then with the world and its resources.”

Born Ellen Henrietta Swallow to an old Yankee family in 1842, Richards grew up on a farm in Dunstable, Massachusetts, not far from the border of New Hampshire, in an area still unconnected from city centers by rail. Her mother, Fanny, was a frail woman who seems to have spent more time in bed than out. Both Fanny and her husband Peter had been trained as teachers. They homeschooled “Nellie,” who herself was frail and petite. But she was sprung from a cloistered girlish existence by a doctor who advised her parents that she must be allowed to run freely in the open air if she was to gain any strength. The outdoors also nourished a scientific bent. She collected plants and fossils and classified what she found in diaries and letters. She noted the topography and flow of streams. She made maps and naturalist drawings.

The Swallows left the farm when Nellie was 16, to move to the larger town of Westford so she could attend school for the first time. Her father ran a general store. She was always busy: looking after her ailing mother and running the house, helping out at the store and making trips—alone—into Boston to drive a hard bargain with suppliers, and always finding time to read and study.

Richards’ letters reveal an independent thinker. She wondered why any woman would choose to marry, knowing what she knew about the dreariness of such an existence from her friends. She was amused by the customers at her father’s general store who debated the relative merits of two leavening agents, baking soda and saleratus, which she knew to be chemically one and the same. Her bright eyes and crooked smile suggested a quick wit, but as an acquaintance once remarked, even her jokes usually made some kind of point.

Along with working at her father’s store, she took on other jobs, such as tutoring and caregiving, and saved up enough money to attend Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York.

At Vassar, Richards’ chief complaint was that this new college for women wouldn’t let the girls study enough, afraid of jeopardizing their students’ health. But she quickly found her way around the rules. She got permission to take more classes than her peers, and to rise earlier than the rest of the dormitory so she could spend more time at the observatory, peering through telescopes. With some pride, she boasted to her parents that she had acquired a reputation for being something of a know-it-all on campus—someone who could be counted on to identify an unfamiliar flower or a new constellation. On the advice of her mentor, astronomer Maria Mitchell, she was saving up money for a telescope. She was not going to waste her hard-earned dollars on a frivolous thing like a new dress for graduation.

Richards showed signs of being a talented astronomer, but even as a student she was filled with a sense of greater purpose. She wanted desperately to put her knowledge to good use. “Pray for me, dear Annie …” she wrote in a letter to her cousin and close friend Annie Swallow, “that I may be of some use in this sinful world.”

After two years at Vassar, she began to look for work abroad, out west, and in Boston. What she really wanted was a job as a chemist. But no one would hire a woman. Finally a prospective employer offered to take her on—if she paid them. Another told her to apply to MIT.

MIT faculty was divided on whether or not to let the Vassar girl into their midst. When she finally was accepted as a special student (the corporation made it quite clear the “Swallow Experiment” did not open the door to other women), President John Daniel Runkle offered to waive her tuition. “I thought it was out of the goodness of his heart because I was a poor girl with my way to make that he remitted the fee,” she wrote, “but I learned later it was because he could say I was not a student, should any of the trustees or students make a fuss about my presence.” She was “shut up” in a private lab, kept apart from her male peers like a “dangerous animal,” Richards wryly observed. So she laid siege to this establishment with the best tools she had at her disposal: a microscope and a sewing kit.

She quickly impressed the anti-Swallow camp with her scientific acumen. William Ripley Nichols, a professor of chemistry, who initially objected to allowing a woman into the labs, soon made her his right hand, relying on her careful water quality analyses, and giving her the credit when he made his report to the Massachusetts State Board of Health. Another skeptic, Professor Robert Hallowell Richards, was soon arguing with himself over the pros and cons of co-education in his diary, even as he became more and more smitten with her and her prowess in his chosen field, geology. He proposed to her as soon as she got her degree. Even so, she made him wait two more years, until 1875, for the wedding. She wanted to be certain he would not stand in the way of her career.

Yet all the while, she made a point of being as useful and unthreatening as possible in the company of her male colleagues, sewing their buttons and mending their suspenders. “I try to keep all sorts of such things as needles, thread, pins, scissors, etc., round and they are getting to come to me for everything they want,” she wrote. “They leave messages with me and come to expect me to know where everything and everybody is—so you see I am useful in a decidedly general way—so they can’t say study spoils me for anything else.”

After all, so much was riding on her success at MIT: her own scientific career, but also the future careers of her sex. “I hope in a quiet way I am winning a way which others will keep open,” she wrote. “Perhaps the fact that I am not a Radical and that I do not scorn womanly duties … is winning me stronger allies than anything else.” She had no ambitions to be Helen of Troy. She intended to be the Trojan horse.

At MIT, Richards began to devote more of her energies to a new discipline that would apply science and chemistry to the urban environment, and in particular to homes. She observed that science and technology had revolutionized industry in her lifetime, but was rarely applied to the home. “Our cooking is proverbially bad,” she said in a visiting lecture at Vassar. “The ventilation and drainage of many of our houses could not well be worse. Why is it? Why do not our housekeepers keep pace with our machine shops?”

It was not enough to study these problems in the lab; Richards wanted consumers to take control of their lives. “The sanitary research worker in laboratory and field has gone nearly to the limit of his value,” she noted. “He will soon be smothered in his own work if no one takes advantage of it. Meanwhile children die by the thousands; contagious disease takes toll of hundreds; back alleys remain foul and the streets are unswept; school houses are unwashed, and danger lurks in drinking cups and about the towels.” There was no clearer argument, in her opinion, for the need to roll out applied science programs to educate and train an army of women.

In 1876, Richards brought the first cohort of female scientists to MIT, to study in a separate space called the Woman’s Laboratory. She did this without pay, negotiating lab space from MIT and raising funds for its equipment from the Woman’s Education Association of Boston. When it became clear that there was no money to pay her as an instructor, she performed her job gratis, even sweeping the lab floor because there was no budget for a janitor. Indeed, she herself kicked money into the project, something she could now afford to do because her new husband came from a much wealthier family than she. She was just thrilled that MIT had agreed to house the lab in the first place.

She was “shut up” in a private lab, kept apart from her male peers like a “dangerous animal.”

Weeks after the Institute voted to admit chemistry students “without regard to sex,” Richards began planning a shopping trip to Europe. “I expect to spend lots of money in Jena for instruments. I am to purchase for the Woman’s Laboratory, which is a sure thing,” she wrote. “All has prospered beyond my expectations.” Under her direction, students analyzed foods for adulteration, and studied air quality and the composition of wools and oils.

Despite Richards’ successes, her challenges with the university were not over. When MIT first admitted Richards as a student, she was not eligible for a degree. Two years later, the Institute relented, agreeing she could present herself as a candidate, and take the necessary examinations—to earn another bachelor’s degree. No matter: Her work testing water supplies and contaminants had already made her a pre-eminent water scientist in the eyes of her colleagues. Still, MIT refused to recognize her dissertation for a doctorate. This, recalled her husband after her death, was the greatest regret of her career. If they had awarded her the doctorate, she would have been not only the first woman to receive a doctorate at MIT, but the first student to receive one. That a woman could get a doctorate before a man did was unthinkable at the time, he remarked.

In 1883, the Institute decided to close the Woman’s Lab and integrate women into the main student body. This was cause for celebration—until MIT’s new president, Francis Amasa Walker, thanked Richards for her services and sent her packing, regretting to inform her there was no longer any position for her at the school. “I do not know that I shall have anything to do or anywhere to work,” Richards wrote, “everything seems to fall flat and I have a sense of impending fate which is paralyzing.”

But Richards was not defeated. She bided her time and waited patiently like a jilted lover for the Institute to wise up and change its mind. Finally, after nearly six months of deliberating, in 1884, MIT offered her a position as instructor in sanitary chemistry under the direction of Nichols, at a salary of $600. She accepted.

In her personal life, Richards was an unusual mix of renegade and conservative. She and Robert spent their “honeymoon” chaperoning Robert’s students in Nova Scotia, while they explored mines. She clearly enjoyed shocking strangers in her explorer’s outfit, which included boots and a shorter skirt than was then the fashion.

Appetite for adventure notwithstanding, Richards believed strongly in the institutions of home, family, and community. She regretted not being able to have children—perhaps a function of marrying later, in her 30s—and had an almost unlimited capacity to care for others: her nieces and nephews, the many students she took into her fold. When there were more guests than beds, she would give up her own room, and discreetly find somewhere to sleep in town after everyone had retired.

But even while Richards was busy working to change legislation and bring in regulations to protect her fellow Americans and make the environments they lived in safer and cleaner, she was equally intent on making change at the household level. If manufacturers understood the “power of chemical knowledge,” wrote Richards, consumers should “know something of chemistry in self-defense.”

Richards’ idea of a housewarming present was to analyze the quality of a friend’s water supply.

At home, Richards practiced what she preached. Her own house in Jamaica Plain—a leafy suburb of Boston—was outfitted with the latest advances in plumbing, heating, and air ventilation. When she began using a gas stove, she had a meter installed in the kitchen to make “a thorough study of the amount of gas required for preparing different dishes and for carrying on various household processes,” recalled her friend and first biographer Caroline Hunt. “She carefully computed, too, the amount of time involved in caring for rugs and hardwood floors as compared with carpets.” Richards’ house was not just a home: It was the epitome of “right living.”

Applying chemistry to the study of the home environment had other benefits, beyond the obviously practical one of making it cleaner and safer. “The woman who boils potatoes year after year, with no thought of the how or why, is a drudge,” she remarked. “But the cook who can compute the calories of heat which a potato of given weight will yield, is no drudge.” To elevate cooking and housekeeping to something that would be valued by society, it needed to be scientifically understood. It needed to be measured.

It’s not clear whether Richards initially saw “household” science as a means to an end—a way of legitimizing the work of women in science—or as an end in itself. Even if her interest in the discipline began as a means to an end—a way to carve out space for herself as a scientist at a time when there was great antipathy toward female scientists’ ambitions—it soon became an end in itself.

Richards was a one-woman consumer advocate, years before Theodore Roosevelt signed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, which outlawed adulterated food and drugs. If women could analyze foodstuffs, air quality, and water in the home—as she herself did—they could make the home into a safer, more hygienic place to live. (Richards’ idea of a housewarming present was to analyze the quality of a friend’s water supply.) This in turn would lead to a healthier, more efficient and productive society.

During Richards’ lifetime, the primary economic function of the household shifted from production to consumption. Science for Richards was a “cure-all” for this brave new world. Armed with knowledge, consumers could keep pace with progress. “If the dealer knows that his articles are subjected to even the simple tests possible to every woman at the head of her house,” she wrote, “he would be far more careful to secure the best articles. Then the housekeeper should know when to be frightened.”

To Richards, the view that ecology didn’t include humans was a dangerous fallacy.

Perhaps not surprising for one who would offer so many prescriptions to how the rest of us should live, Richards and her husband developed an acrostic to guide their own lives: FEAST, which stood for food, exercise, amusement, sleep, and task. According to Pamela Swallow in her biography of her ancestor, The Remarkable Life and Career of Ellen Swallow Richards, Richards would rise at 5:30 every morning and meditate before waking her husband for a brisk 2-mile walk around Jamaica Pond, no matter what the weather. She and her friends would go on regular excursions to hike and explore neighboring woods and seaside towns, flipping a coin to decide which path to take. “Remember human energy is the most precious thing we have,” Richards wrote. Getting the right food, exercise, amusement, and sleep would optimize it.

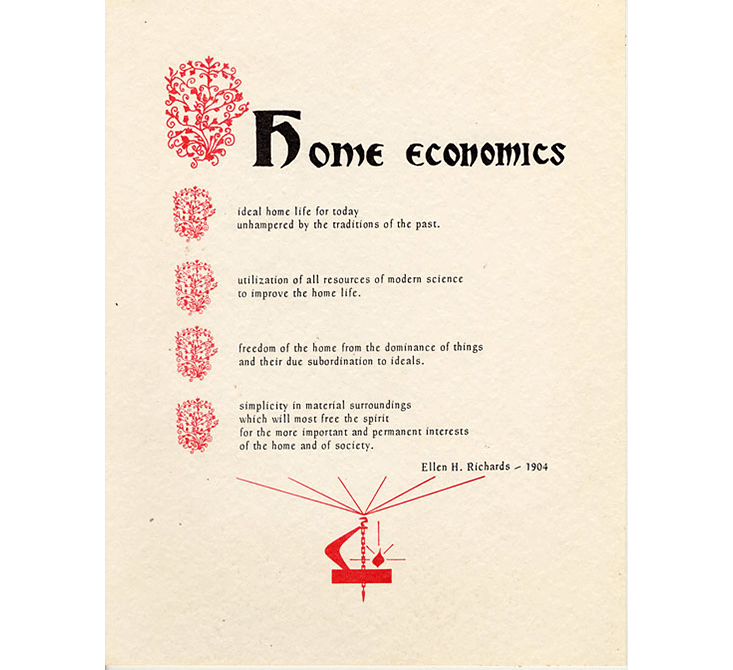

In 1892, Richards went public with her ideas of right living, announcing to great fanfare that she had formed a new discipline. “As theology is the science of religious life and biology the science of life … so let Oekology be henceforth the science of normal lives,” she said grandly in a lecture that made the front page of the Boston Daily Globe.

Richards had borrowed the term Oekology from Ernst Haeckel, who first described ecology as “the total relations of the animal to both its inorganic and organic environment.” Fluent in German, she had written to the German biologist to ask if she could develop this field. But Richards’ vision was more human-centric. Tracing the word back to its Greek roots (oikos means house), Richards did not distinguish between the house and the landscape on which it was built: Both have a profound effect on us.

Shortly after Richards introduced ecology to the American public, her male colleagues picked up the term. Their vision of ecology “tended to view the activities and institutions of humans as lying outside the realm of ‘natural’ interrelationships,” Eugene Cittadino observed in a 1993 paper, “The Failed Promise of Human Ecology”—which, incidentally, doesn’t mention Richards.

To Richards, the view that ecology didn’t include humans was a dangerous fallacy that imperiled both our health and that of our environment. “In everything else he has advanced,” she wrote of mankind, “but in his intimate personal relations with nature and natural force he has acted as if he believed himself not only lord of the beasts of the field, but of the very laws of nature without understanding them.”

After ecology was commandeered by her male colleagues, Richards tried once again to roll out a broad, scientific discipline that would reflect her ideals. In 1910, a year before her death, she laid out her life’s philosophy once and for all in her book Euthenics, The Science of Controllable Environment: A Plea for Better Living Conditions as a First Step Toward Higher Human Efficiency. “Right living conditions comprise pure food and a safe water supply, a clean and disease-free atmosphere in which to live and work, proper shelter, and the adjustment of work, rest, and amusement,” she wrote.

Richards continued to champion her ideas as she suffered from a worsening heart condition. Even an acute attack of angina on the way to a lecture one night didn’t prevent her from painstakingly taking the stage. She remained vivacious and energetic, and even her husband didn’t comprehend the seriousness of her illness until she took a bell to bed with her, telling him she might need his assistance in the night. After a week of being bedridden, she died of heart disease in 1911. She was 68.

Euthenics gained some traction in the decades following her death—Vassar even established a program to teach it—but without Richards to champion the discipline, it petered out. Human ecology (also a term she flirted with) was another discipline that limped along for much of the 20th century, not sure if it wanted to be a social science, or a biology-based complement to ecology itself. Despite Richards’ great ambitions for home economics, another discipline that she founded, it often devolved into sewing and cooking classes, acting as a tool for ghettoizing women (or at least sidelining them), rather than lifting them out of drudgery.

What made Richards so unique—both then and now—was her ability to see the world more holistically than so many of her colleagues. It may have also been her downfall. There was no one tidy discipline or lineage to keep her legacy alive. The group that did continue to noisily celebrate her after her death—home economics—probably did her a bit of a disservice, unintentionally, because they made it easier for everyone to forget the many other contributions she had made over the course of her career.

Richards was first and foremost a scientist who was unafraid to wade into the messiness of social reform and policy-making. Unlike so many of her peers, she did not draw a line between the built environment that human beings lived in, and the natural environment she so loved. She saw them for what they were: two rooms in the same house. And like any good housekeeper, she knew, we each had a responsibility to keep both rooms clean.

Sasha Chapman is a Toronto-based writer who began researching the life of Ellen Swallow Richards as a 2015-2016 Knight Science Journalism Fellow at MIT.

Additional Reading

Hunt, C.L. The Life of Ellen H. Richards Whitcomb & Barrows, Boston (1912).

Swallow, P.C. The Remarkable Life and Career of Ellen Swallow Richards John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey (2014).

Musil, R.K. Rachel Carson and her Sisters: Extraordinary Women Who Have Shaped America’s Environment Rutgers University Press, New Jersey (2014).

Richards, E.H. The Cost of Shelter (1905).

Richards, E.H. Euthenics, The Science of Controllable Environment: A Plea for Better Living Conditions as a First Step Toward Higher Human Efficiency (1910).

Richards, R.H. Diary of Robert Hallowell Richards (1873).