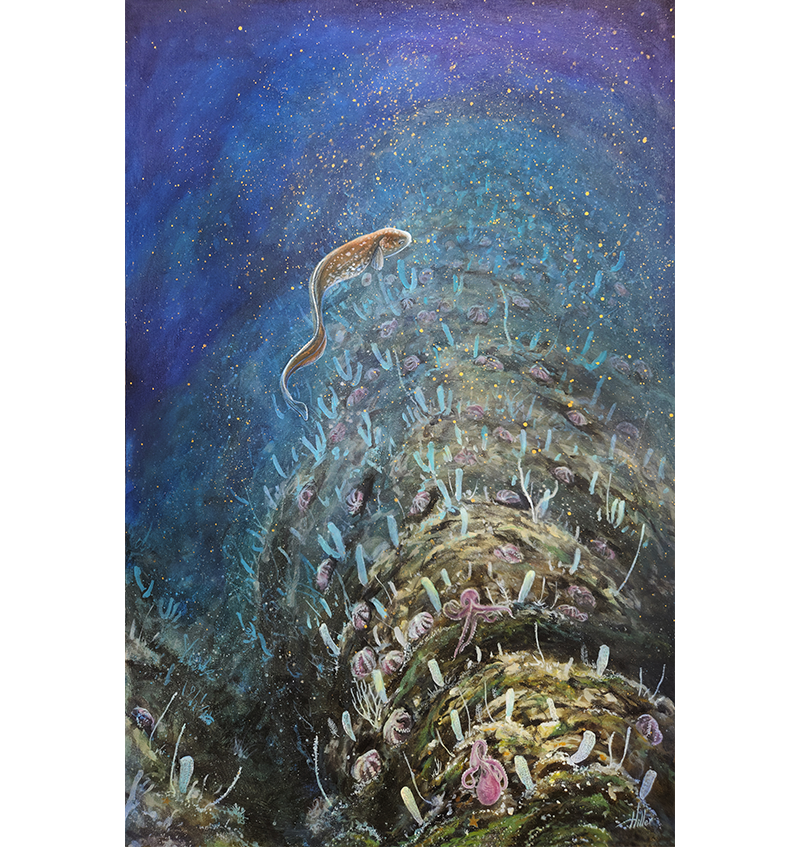

Tripod fish live past the reach of sunlight and sense with long fins that look like stilts grazing the ocean floor. The fish challenges our conventional idea of life, says painter Carlos Hiller, as do many other creatures he recently encountered in the deep sea.

Hiller was one of two artists who shipped out with Falkor (too) on an expedition to a number of undersea mountains, or seamounts, 155 miles from Costa Rica’s western shore. The expedition also included more than a dozen scientists, a journalist, and a government observer.

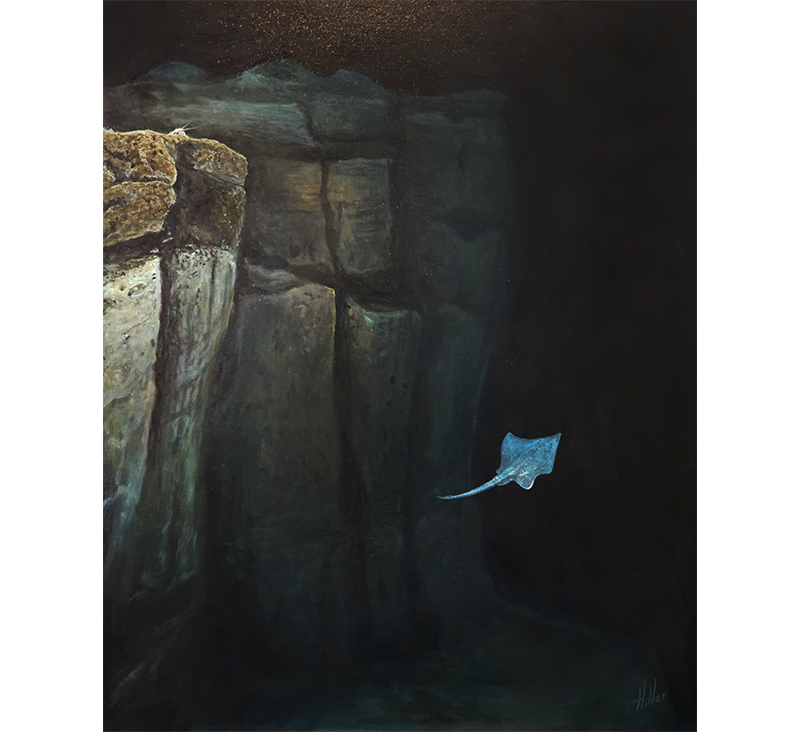

Hiller has painted the marine creatures and landscapes of Costa Rica for 25 years. “The sea is my passion, and it floods my canvases,” he says. But even he was not prepared for the sheer overflow of this trip. Seamounts harbor biodiversity we are only just beginning to fathom; on this expedition, the Falkor (too)’s remotely operated submersible crossed paths with everything from millennium-old corals to brand new baby octopuses, beaming it all in real time to screens on the ship.

“Many images—too many—crowded my brain and struggled to jump onto the canvas,” Hiller says. He rendered the most astonishing creatures and scenes in paint using his signature style, which combines rigorous detail with dramatic flair. Seeing these creatures gave Hiller a renewed sense of the fantastic, he says: “I can imagine the most surreal creature and there is a chance—however small—that it exists there.”

Rather than taking the submersible’s point of view, this painting, El Pez de Salvador, shows two tripod fish caught in the glow of the submersible’s LEDs—likely the first light ever cast on them.

During the expedition’s 20 days at sea, Hiller often worked from dawn to dusk. “Painting while on the ocean, rocked by the slight swell of the sea, is wonderful,” he says. But “painting inside the main lab—surrounded by microscopes, TV screens, equipment, chambers full of samples, lab benches, and scientists—is even better.”

The R/V Falkor (too)’s remotely operated submersible, ROV SuBastian, was the eye of the expedition, toting cameras that streamed footage to the ship’s control room (as well as to an online livestream). Hiller’s first few paintings “portrayed what SuBastian showed, emotionally enriched through my own perception,” he says.

This work, El Dorado, depicts an octopus nursery at the Dorado Outcrop, a 9,800-foot deep seamount gently warmed by hydrothermal vents. Researchers had seen mother octopuses brooding at the outcrop before, but were unsure whether eggs could survive there long enough to hatch. When newborn octopuses flitted past the cameras, there were “screams and tears,” says Hiller.

Hiller and the expedition’s other artist, Michel Droge, were “in the middle of the action,” Hiller says. A typical day on board involved “assisting with sample processing, grabbing tools for the scientists, and carrying samples to the cold rooms.”

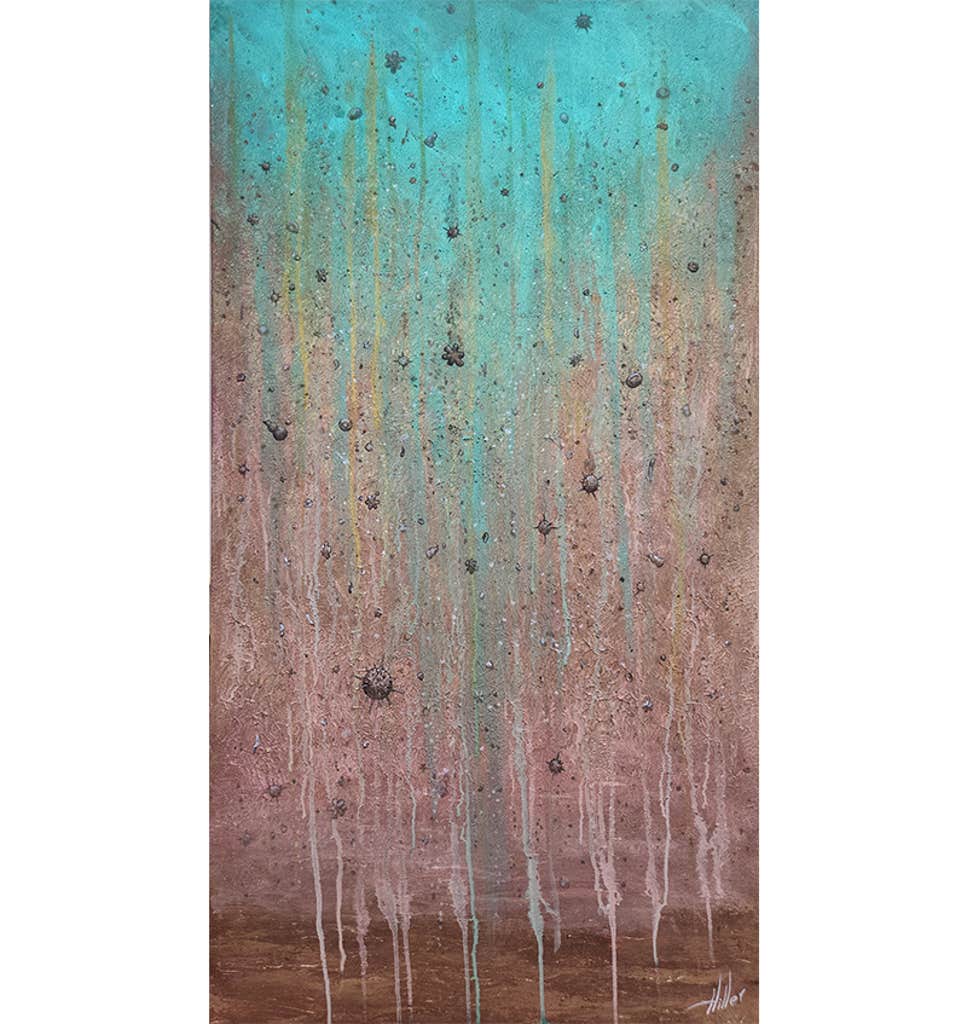

Hiller made these processes part of his art. He incorporated leftover samples of deep-sea sediment into some of his pigments, for example, including those he used in this painting, Lluvia Pelágica (“Pelagic Rain”).

Over 90 percent of Costa Rica’s national territory is under water. “This may lead us to think of the ocean as an infinite surface covering an empty realm of darkness,” says Hiller.

Now that he has been let into the depths—and seen how full they are—“I feel that I have a more complete, expanded perception of the ocean, which makes me love it even more,” he says. “I have to find a way to reach a lot of people, telling them by painting what I could see there.” ![]()

Carlos Hiller is an artist who specializes in portraying the underwater world. Hiller spreads a message of ocean protection through public murals and environmental education. His artworks are present in private collections throughout the world and used as references for underwater art. You can find his work at https://carloshiller.com.

Prefer to listen?