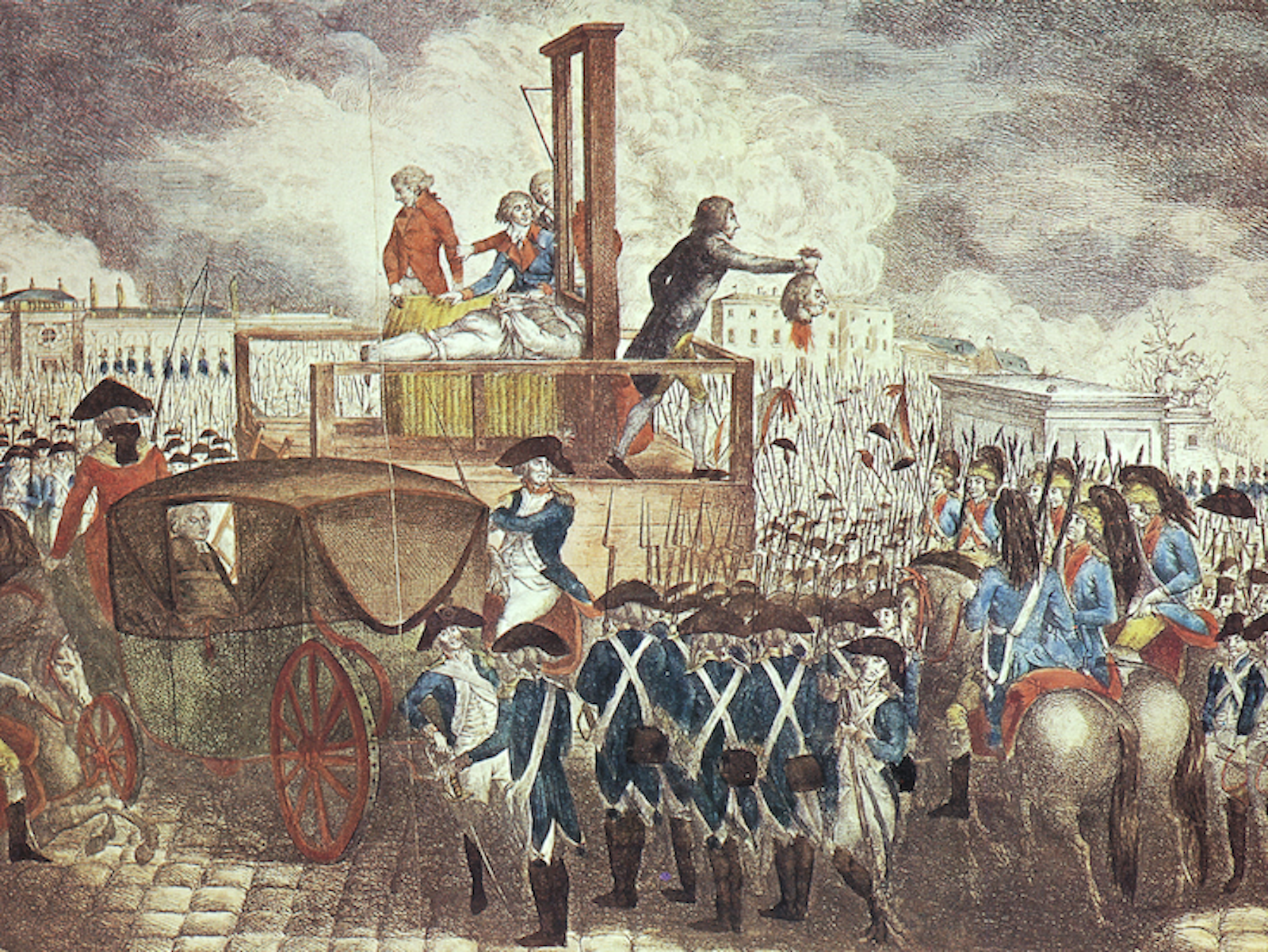

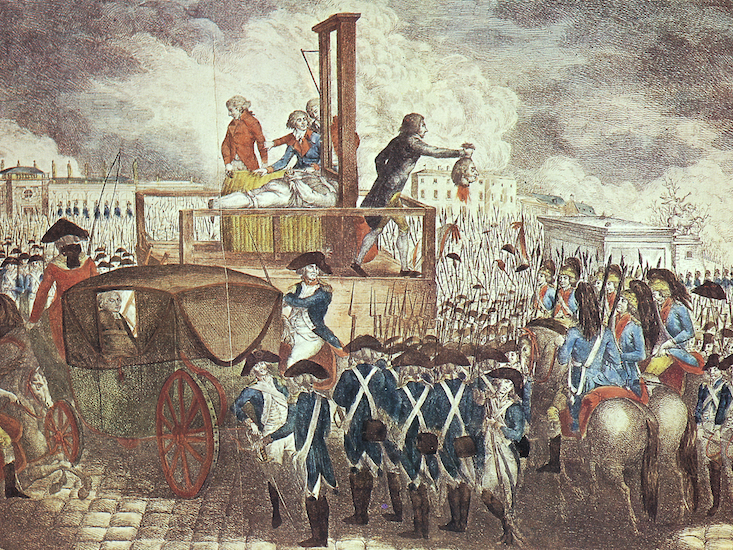

On a damp, foggy January morning in 1793, Louis XVI, besieged monarch of France, stood before a guillotine. To some 20,000 of his angry subjects, Louis declared: “I die innocent of all the pretended crimes laid to my charge. I forgive all those who have had any hand in my misfortunes, and I pray that my blood may be of use in restoring happiness to France—and you, unhappy people!”1 The rest of his speech was cut short. The king was strapped to a plank, slid through the “widow’s window,” and decapitated.

What Louis could not have known was that one root of his “misfortunes” was not any one of his subjects. It was El Niño, the climatic fluctuation that has sown misfortune for humankind for millennia. Today, as global temperatures rise, El Niño events will likely become more dramatic—causing longer, drier droughts, extreme floods, and more unpredictable weather. Stories of how El Niño shaped history are thus more than mere curiosities, says Brian Fagan, author of Floods, Famines, and Emperors: El Niño and the Fate of Civilizations.

“You cannot study climate change without looking at human experience of climate in the past,” he says. We might live in a world of billions more people, but past El Niños can still offer insights into human behavior. “They won’t tell you how to do something,” Fagan says, “but they can give you precedents for how you might.”

El Niño is one stage of a much larger cycle in Pacific Ocean weather patterns—a cycle known as the El Niño-Sothern Oscillation, or ENSO. “El Niño” happens when westerly trade winds cross the Pacific and weaken; air pressures plummet in the eastern Pacific as a result, and warm water builds up around the Americas. The force and direction of the Pacific winds have worldwide impacts, in ways that are still not completely understood. “Each El Niño episode,” according to NASA’s website, “has a unique timing and variations in impacts.”

Take, for example, Europe: It’s believed that as the South Pacific Ocean warms, air pressure drops in the North Pacific, causing anomalies downstream over North America and northwestern Europe. These changes can speed up the polar jet stream, the fast-moving air current that circles Earth’s upper latitudes like a belt, and increase activity in swirls of air over the Atlantic called eddies. All of this can add up to very strange weather—like that which France saw in the late 1700s.

The French Revolution sprouted as the harvest, plagued by a frigid winter, died. It was so cold in winter of 1787-88 that wolves were said to have left the Alps to stalk the countryside. Spring wasn’t any better, as massive hailstorms laid fields to waste. In the next year, bread prices doubled. As another excessively cold winter descended, a fifth of Paris, according to church records, relied on charity for food. Bakeries and granaries were robbed, and pamphleteers demanded the Estates General, the legislative assembly of France’s three social classes, address the dwindling bread supply.

They didn’t do so fast enough. That summer, France rose in revolt. On July 14, 1789, peasants stormed the fortress of Bastille, in a desperate raid for weapons and gunpowder.

El Niño alone did not depose France’s monarch; political and social issues had long been simmering below the surface, waiting to be channeled by radical Enlightenment philosophy. But the shortages brought by El Niño pushed these issues to the forefront. Instead of a series of changes that might have occurred over decades, El Niño helped topple the system all at once.

The French monarchy is not the first empire El Niño has deposed. Just look to Peru, formerly the home of the Moche civilization—a once-flourishing empire which, by the end of the 7th century, El Niño almost washed off the map.

“There is an extraordinary amount of hitherto unnoticed environmental instability in modern history.”

For five centuries, the Moche, ruled by warrior-priests in massive adobe temples, had controlled a sprawl of fishing towns and canal-irrigated fields on the Peruvian west coast. It was a civilization seemingly well adjusted to the region’s variable climate—that is, until the rain vanished for 30 years. Grain supplies dwindled, leaving only anchovies for food. Then, near 600 AD, the anchovies disappeared, too, and rain returned with a vengeance. Floods swept away fields and swallowed towns. As the rain fell, the bodies of human sacrifices built up in the mud—attempts by the Moche rulers to appease the gods and slow El Niño’s chaos.

In desperation, the leaders of the Moche chose to abandon their capital, moving north and inland to two new cities. But El Niño was not done with the Moche. Less than a century later, it returned, bringing another cycle of floods and drought. Famine and revolt followed; around 700 AD, both cities were abandoned.

The worst effects of El Niño are most often borne by the poor. This has been seen time and again in India, where El Niño’s impacts on harvest-bringing monsoons can lead to famines of astonishing devastation: During just one, in 1877, an estimated 18.5 million Indians perished.

India’s monsoon rains develop only when summer air pressures are lower over India than the Pacific Ocean, encouraging moisture-laden winds to blow toward land and form rainclouds. When the warm waters of El Niño gather in the central Pacific, the resulting convection currents land squarely on the Indian subcontinent, bringing high pressures that deter rain. “July 1 came, and no rain of any consequence had fallen,” wrote William Digby, a British writer living in India, in 1877. “If no rain falls before end of the month, the dry crops…will completely fail, and results will be most disastrous.”

Digby was soon proved terribly right: In 1876 and 1877, the monsoon never arrived. India’s traditional protections against drought, such as family-regulated grain reserves within both households and villages, may have made things easier on the population. Yet these defenses had been dismantled. Surplus grain and rice had been exported to England, and the Viceroy of India, Lord Lytton, maintained a laissez-faire trade policy that allowed grain prices to spike when supplies dropped. (Lytton also denounced famine-relief efforts as “humanitarian hysterics,” believing they would bankrupt the country.)

The effects of these policies may reverberate to this day. In his book Late Victorian Holocausts, historian Mike Davis posits that the combination of colonialism and climate at the end of the 19th century, in India and many other places, formed the roots of today’s third world.

El Niño is an “episodically potent force in the history of tropical humanity,” he says. “If, as Raymond Williams once observed, ‘Nature contains, though often unnoticed, an extraordinary amount of human history,’ we are now learning that the inverse is equally true: There is an extraordinary amount of hitherto unnoticed environmental instability in modern history.”

Footnote

1. The exact phrasing of this quote is disputed among historians, but its meaning remains essentially the same regardless of the source. This wording is drawn from “Judgment and Execution of Louis XVI, King of France,” written by the French clergyman Henry Goudemetz following the events of 1793; it was translated into English in 1796.

Claudia Geib is an editorial intern at Nautilus. Follow her on Twitter @cm_geib.