Our brains, perched atop a network of nerve cells that ascend the length of our bodies, are thought to have arisen once in an animal hundreds of millions of years ago and then evolved over time. However, new findings suggest instead that brains and nervous systems originated multiple times from scratch.

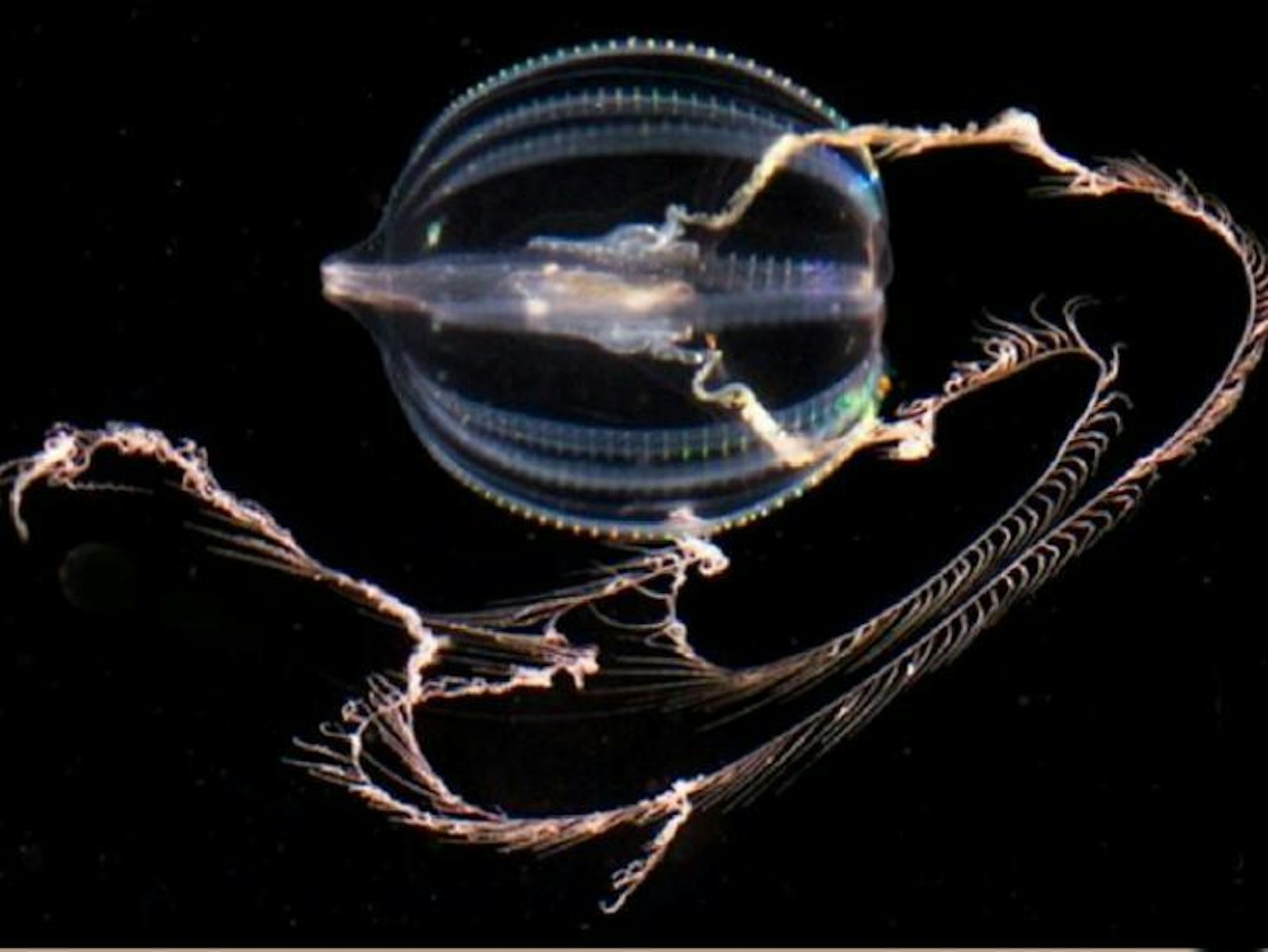

The findings, published today in Nature, highlight an ancient and gelatinous marine predator called a comb jelly. Unlike pulsating jellyfish, comb jellies swim by “rowing” their many hair-like cilia, which are arranged in rows called combs. They possess rudimentary brains and sophisticated nervous systems replete with elongated cells that communicate through synapses much like our own. Some comb jellies show mirror-like bilateral symmetry, as do we. And like most animals, their muscles derive from a middle tissue layer, which does not exist in jellyfish or sponges, another ancient type of aquatic creature.

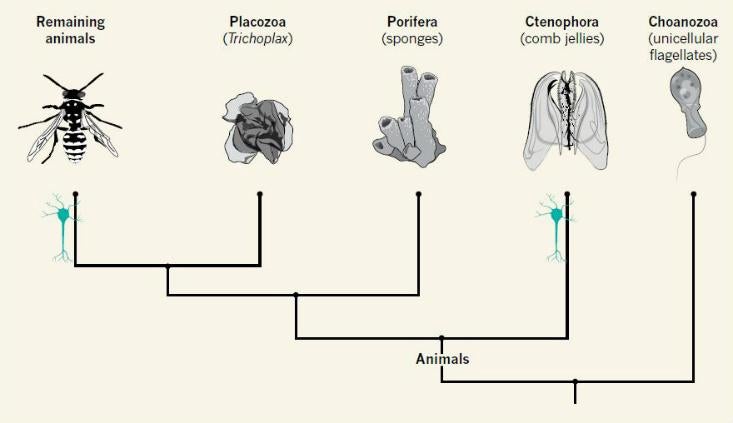

So it’s little wonder that biologists have long placed the comb jelly group close to worms, flies, and humans on the evolutionary tree of life; sponges emerge at the base, meaning that this group appeared first. In this traditional view, complex body parts like the brain and muscles arose gradually, and only once, since those parts look similar across related animals, and the chances of that same evolutionary process being repeated seems slim.

But this scenario was shaken by a report in Science last year, which suggested that the comb jelly group emerged before jellyfish and even the brainless, muscle-less sponges, more than 550 million years ago.

Some biologists doubted the rearrangement because it implied two equally uncomfortable possibilities: that the ancestor of all living animals had true muscles and a rudimentary brain, and then sponges and jellyfish lost those parts without a trace; or that the great animal ancestor was simple, and comb jellies evolved separately from all the other animals, yet ended up with rather similar nervous systems, muscles, and bilateral symmetry. When paleontologist Graham Budd heard the news last year, he said, “It is effectively saying animals evolved twice. Frankly, I’m not ready to believe it.”

Without a time machine, it’s impossible to know what our great ancestor looked like. However, today’s report adds more support to the notion that she was simple and comb jellies independently evolved their complex body parts. Leonid Moroz, a neurobiologist at the University of Florida’s Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience, and his colleagues confirm comb jellies’ position below sponges at the base of the evolutionary tree with an analysis of genetic sequences from 11 comb jelly species.

What’s more, Moroz’s team demonstrates that comb jellies’ nervous systems do not use most of the genes and proteins that all other animals rely on to develop and operate theirs. For example, comb jellies do not appear to have serotonin and dopamine, two neurotransmitters that our brains could not function without. And a gene called elav, which is active in all other animals’ nervous systems, only turns on in non-neuronal places in the comb jelly body, suggesting that it serves a different function. Likewise, a unique set of genes appears to underlie comb jelly muscles.

In an essay for Nautilus called “Evolution, You’re Drunk,” I described how hypotheses entrenched in the notion that evolution leads toward increasing complexity have recently begun to teeter. Now Moroz’s study adds another shove. It seconds the finding that simple sponges, long placed at the base of the evolutionary tree, actually evolved after the sophisticated comb jelly group arose. The story of how complexity evolves is more complex than scientists realized.

Furthermore, the brain—the epitome of complexity—seems to have sprouted up at least twice over evolutionary time. This clashes with the traditional notion that complex, multifaceted features come about in a very specific way, and each emerges just one time. “What everyone has said about complexity is wrong,” Moroz says. “It can happen more than once.”

Finding that comb jellies independently arrived at similar ends as other animals might also have surprised the late paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who famously doubted that animals would look the same today if the world were to begin again—if we could replay “the tape of life.”

Is such convergence in design a coincidence? Probably not, guesses Andreas Hejnol, an evolutionary developmental biologist at the Sars International Centre for Marine Molecular Biology in Norway. “If you need a fast communication system, it helps to have extended cells that communicate through chemicals,” he says. In other words, the structure of the nervous system reflects its function. So if intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, it’s not too far a stretch to think it could possess a brain comprised of trillions of neurons. Hejnol asks, “How else could it be?”

Amy Maxmen is Nautilus’ senior editor.