The water flowing down the stream’s banks sends a soft and consistent murmur through the forest. The flow, however, is far from continuous. At one point the cool water swirls in eddies and gathers in still pools, but then—almost accidentally—it surges forward and slips quickly over the ledge. It crashes loudly, bubbling up in a choppy white cauldron before slowing again in a second silent pool.

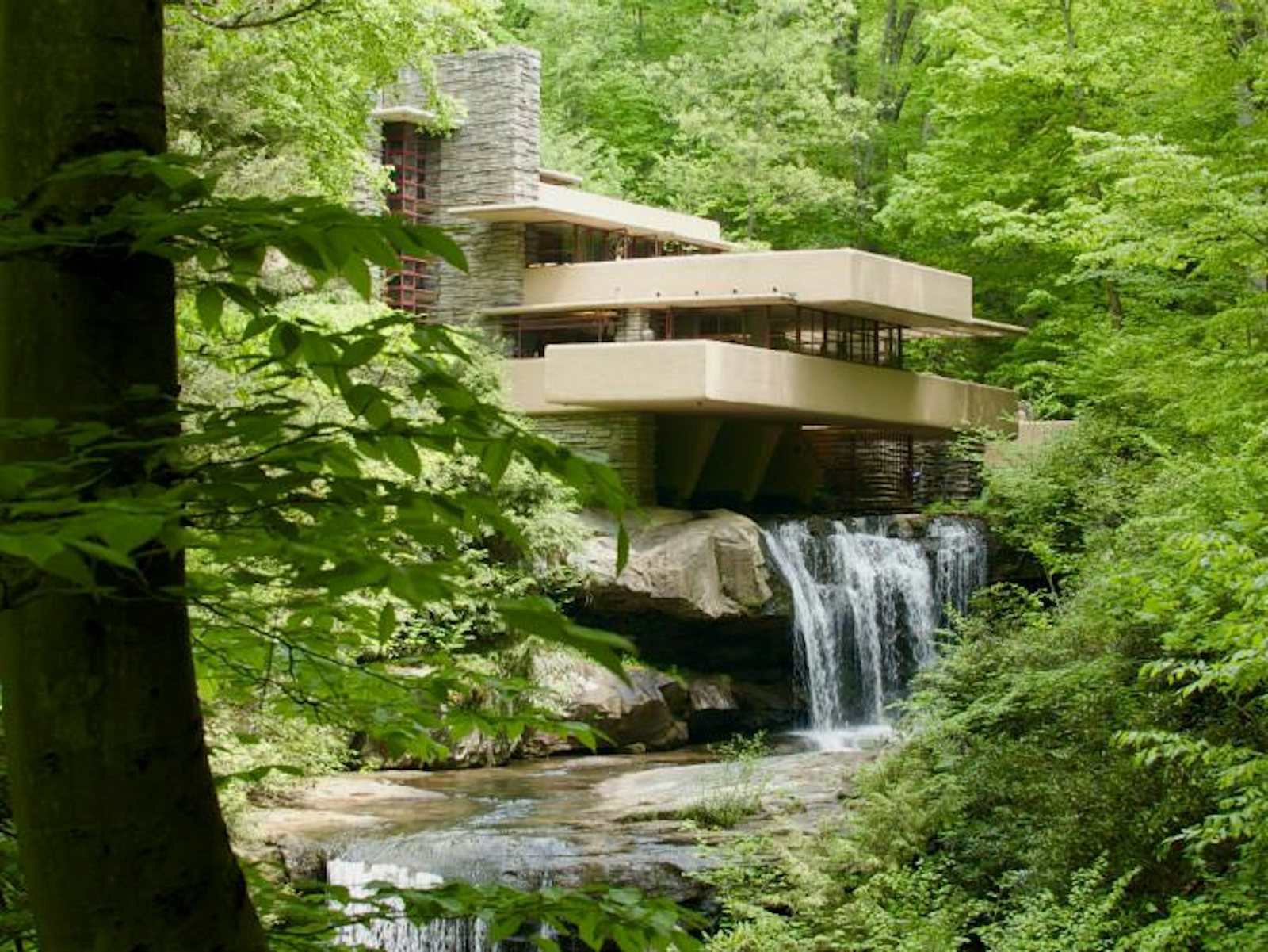

Some 30 feet above that first ledge is a house that juts out from the side of a hill in a series of concrete trays. Designed by Frank Lloyd Wright shortly after the Great Depression, the house appears to float over the falls. It’s easy to see why it’s arguably America’s most famous home.

Wright completed Fallingwater in 1937. In January 1938, Time magazine’s cover story proclaimed it as the famous architect’s most beautiful job. In 1943, Ayn Rand released her novel, The Fountainhead, some of which was inspired by the house. And today over 135,000 people tour it each year.

I visited Fallingwater in May, shortly after winter had melted into spring. Although the rhododendrons had yet to bloom, the surrounding vegetation was a welcoming green. From a distance, the horizontal and vertical elements of the scene were the most striking. The horizontal pools of water are mimicked in the main horizontal elements of the house: the concrete slabs, or so-called cantilevers, which jut over the falls. The cantilevers are then set into the vertical elements: the hillside itself and the great stone columns, which mimic the vertical waterfall.

“It’s as though he [Wright] took his inspiration from the ledges that the water is falling over and tried to echo them in the house,” says Barry Bergdoll, a professor of art history and archeology at Columbia University.

As I entered the house, it quickly became clear how much the interior space is actually oriented to the outside. A boulder protrudes through the living room and doubles as a hearth. Low ceilings direct attention outside. Windows open outward from wall corners, leaving no panes to obstruct the view. And every room has its own private balcony. The focus is always on nature.

“But the coup de grâce that just melts every architect’s heart is this little stair that comes down from the living room,” says Stephen Atkinson, a practicing architect in California. “You open this crazy hatch and you can walk downstairs just to the very surface of the water.”

The lines between the house and nature are blurred. As such, Wright’s creation is often called organic.

But to say that Fallingwater is simply a meditation on nature would miss the point—which, sadly, I did. I walked away from Fallingwater thinking that the house was a beautiful representation of the juncture where nature and architecture meet and nothing more. Then I emailed Neil Levine, a professor of history and architecture at Harvard University, to ask for an interview.

Levine replied promptly, but to my dismay, he told me he was too busy to talk. Furthermore he mentioned that I would do better not to engage with jargon like “organic architecture.” I was slighted, yes, but also intrigued.

In 2011 Levine published an essay titled “The Temporal Dimension of Fallingwater,” where he argues that time—and not just nature—is crucial to Wright’s design. This temporal element was a direct consequence of the natural setting. The stream, including the waterfall, isn’t only a place where the horizontal meets the vertical, but also where the motionless meets the turbulent, the silent meets the thundering, and the finite meets the infinite. The stream is some combination of both sides. By placing the house above the falls, Wright furthers this juxtaposition.

Although the stream below is boundless, continuously flowing downward from the hills and tumbling through the falls, the house above represents a single moment, frozen in time. Atkinson likens that moment to the leap of a ballerina. Wright tried to capture that leap, transforming the finite into the infinite.

This relationship is furthered inside the house where, ironically, the falls disappear from sight. “You’re intimately connected to the waterfall, but at the same time, bizarrely, you’re incredibly removed from it,” says Atkinson. “You’re divorced from the falls itself and yet closer, which gives you a real visceral connection to the water.”

Had the house been placed in view of the falls, one would passively look at them every so often. We have a tendency to take in visual images and quickly sort them, reducing nature to something easily defined. But sound is in a way harder to process, let alone quickly define. By placing the house above the falls, one is actively—and continuously—engaged with the falls.

Wright doesn’t give precedence to the continual over the momentary. Instead, the house is both boundless and bound, infinite and finite, stone and liquid.

Shannon Hall is an editorial intern at Nautilus.