In the 1980s, a bioengineer named Norm Heglund was doing field work in Kenya, hoping to uncover the secrets of locomotion. It was a good gig. Heglund and his team spent their days shooting wild animals with tranquilizer darts in Kenya’s national parks then dragging them back to a research station, run by the East Africa Veterinary Research Organization, in nearby Muguga for testing.

Every day, the wives of local colleagues stopped by the lab to chit chat. They carried impossibly huge bundles of food, clothing, or other supplies perfectly balanced on top of their heads. During one lunch break, a few weeks into his stay, he realized something.

“These weren’t little loads,” Heglund told me when I spoke to him for my new book, The Body Builders: Inside the Science of the Engineered Human. “They were huge loads on their heads and it was just pretty amazing. We had all this equipment there for measuring oxygen consumption and so we thought, ‘What the heck, this is an opportunity! Let’s just measure how much oxygen is consumed by these women.’”

Heglund was amazed at what he discovered. When walking on the treadmill, the women were capable of carrying loads equaling 20 percent of their body weight on their head with zero extra metabolic cost. It seemed to require no extra effort whatsoever. Further, at an extra metabolic cost, these women were capable of carrying 60 percent—even 80 percent of their body weight on their heads.

Heglund tied lead weights to a bicycle helmet to see if he could replicate the feat. It caused such a strain on his neck, he and his western colleagues didn’t feel that they could safely carry more than 15 percent of their own body weight. “If you kept your head just really vertical and lined up it was okay, but if you got just a little out of equilibrium, it felt like it was going to break your neck,” he recalls.

The answer to the mystery had to do with the intricacies of the pendulum-like motion the women used while walking with the loads on their heads.

When the Kenyan women stood still on the treadmill, wearing a mask that measured the amount of CO2 they exhaled, it didn’t matter whether they had no load on their head, or a large load on their head—if they weren’t moving, they seemed to be expending no more energy whatsoever. The line on the instrumentation was so flat, in fact, that Heglund wondered if it was broken—until he asked the women to start walking and the amount of energy burned shot up.

Heglund realized there was only one conclusion: Unlike the rest of us, the African women were supporting the load with the structural components of the body, rather than metabolizing tissues of the body. They were balancing it perfectly on their bones, without the aid of any muscle, tendon, or supporting structures. Over time, Heglund showed, the bones and bodies of the African women had adjusted to perfectly support the head weight in the most energy efficient manner. The structure had adjusted so it aligned in an ideal formation to keep the weight off the muscles.

The adaptations of the Kenyan women also allowed them to walk while expending less energy. In subsequent experiments, Heglund compared their metabolic processes to data from a huge U.S. Army study, conducted in the early 1980s, in which scientists measured the metabolic cost for hundreds of new recruits carrying heavy backpacks. At the slowest of walking speeds, virtually a crawl, the male U.S. Army recruits could carry heavy loads at a cheaper metabolic cost—with less effort than the Kenyan women. But as soon as they sped up the advantage disappeared. In fact, at high speeds, by the time you upped the load to 60 percent of body weight, the Kenyan women had almost a two-fold advantage.

Intrigued by his data, Heglund would return to Kenya two more times over the years, on a Fulbright Scholarship and with grant money provided by the U.S. Army, to figure out what it was about the women’s walking mechanics that allowed them to do so. The answer to the mystery, he discovered, had to do with the intricacies of the pendulum-like motion the women used while walking with the loads on their heads.

Scientists have known for decades that when humans walk and run, we recycle energy. When we run, the spring-like tendons compress on impact, storing elastic energy. When our foot leaves the ground, the tendons release the energy like a coiled box spring, propelling us upward and forward, and into our next stride. Essentially, explains Heglund, we bounce along, like a basketball.

Our calf muscles, meanwhile, shorten and lengthen primarily to modulate stiffness, effectively serving as a volume switch for the Achilles tendons. The stiffer the muscle, the more it pulls on the tendon, which effects how tightly the tendon will coil. Consider, for instance, how we deal with a puddle while jogging. To modulate our step, we flex, stiffening the calf muscle, bringing the tendon in tight, to allow us to take a short stutter step and bring us up short. Then we release all that stored energy to vault over the water.

If when we run, we bounce, then when we walk, the way our legs conserve energy resembles the swinging of a pendulum, another manmade device ingeniously designed to conserve and recycle energy. In walking, like a pendulum, the leg alternates, expending energy and losing speed, as it pushes upwards against gravity, and regaining energy, momentum and speed on the way back down, as the same gravitational forces that slowed it on the way up now propel it forward. The release of this recycled energy from the leg, by some estimates, accounts for up to 70 percent of the propulsion driving each stride when we walk, leaving only 30 percent to be supplied by the muscles.

A perfect pendulum, swinging back and forth unimpeded, would preserve 100 percent of its energy—the original push downward by gravity first transforms into potential energy as the momentum carries the weight on the end upwards to the top of its arc. Then that energy is released back as kinetic energy carried by gravity in the opposite direction, until it reaches the top of the arc, repeating the cycle.

When most of us walk at our optimal speed, however, we lose 40 percent of our energy with each stride at two specific points: at the top of our stride, and at the bottom, when our foot hits the ground. The African women experience identical motions. But when they added weight to their frame, their stride somehow adjusted—invisible to the naked eye—allowing them to transfer around 80 percent of the energy forward. The weight seemed to transfer more smoothly, especially at the lower end of the stride. The skeletal and muscular structure of the African woman had adjusted over time in a way that ensured the most efficient distribution of weight.

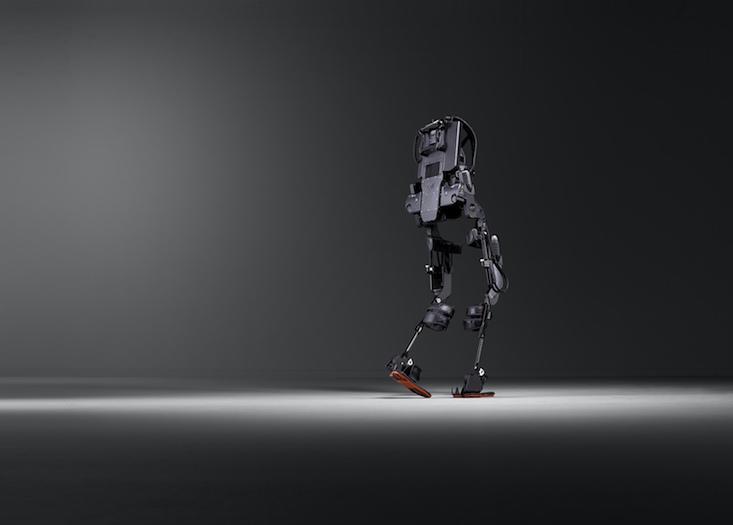

It’s probably too late for most of us to develop similar skeletal adaptations. Heglund would conclude that the structural adjustments these African women had developed emerged only after years of daily practice carrying heavy loads—a practice that began when they were young. But the lesson of the women is not lost. By understanding, measuring, and taking advantage of the way the constituent parts of our skeletons align to transfer weight through our bodies and to the ground, a new generation of engineers are developing artificial exoskeletons that promise to provide new mobility to the disabled, and augment the able-bodied.

California-based Ekso Bionics, for instance, has developed an exoskeleton containing a sophisticated array of sensors that monitor subtle shifts in a user’s weight, and then uses complex mathematical modeling to dictate how a titanium frame should move to counterbalance the load, and help users move forward with the least available effort. Its device is the first authorized robotic exoskeleton to help those who have suffered a stroke or spinal cord injury regain mobility. Using such a device, someday soon, the rest of us will likely be able to carry hundreds of pounds with minimal effort. You’ve probably already thought of more than a few ways you might use that extra muscle.

Adam Piore is the author of The Body Builders: Inside the Science the Engineered Human, which was published in March. Follow him on Twitter @adampiore.

WATCH: The physical anthropologist Ian Tattersall on whether we are still evolving.