This here is my favorite cabinet,” Hein van Grouw tells me as we walk around the back rooms of the Natural History Museum at Tring, 30 miles northwest of London as the crow flies. He pulls the steel double-doors open, revealing a menagerie of stuffed birds. On the top shelves there are snipes, rails, and pigeons. Below them are thrushes and blackbirds. And filling the bottom, sliding shelves with smaller passerine birds: finches, starlings, and warblers.

Mostly collected by Walter Rothschild in the 19th century, all these birds share one thing in common: They have each inherited a genetic mutation—or mutations—that give them abnormal plumage. Their strange colorings make it difficult for me to identify even the most familiar of garden birds. One that is an odd mosaic of dark brown and milk-chocolate colors is apparently a melanistic chaffinch. Other birds seem faded as if time has sapped their vibrancy. A few are snow white.

Every time I point and ask, “What mutation is that?” van Grouw tells me, with “99 percent accuracy,” sometimes ruffling a few feathers to confirm his judgment. Since childhood he has bred pigeons and ring-necked doves with unusual plumage, crossing different mutants and seeing what hatches. As bird group curator at Tring, he has traveled to collections across the world in order to classify, understand, and name the many different aberrations in avian plumage. Birdwatchers, news articles, and even scientific papers commonly use just one or two simplistic terms to describe many distinct color variants. van Grouw hopes to change this.

In normal circumstances, sans genetic mutation, most bird feathers are pigmented with melanin, which is added to feathers as they grow out from the skin. There are actually two versions of melanin—eumelanin and phaeomelanin—and this molecular duet can impart shades of gray to black, or ruddy brown to pale buff, respectively. Other colors, such as bright reds and yellows, derive from carotenoids contained within food. The yellows and reds of parrots and parakeets come from psittacin pigments, a variety unique to that category of birds, while the iridescent blues and greens of birds such as kingfishers and peacocks come from their special structural coloration. But most oddities derive from melanin production that’s gone awry somewhere.

Embodied by the chaffinch I saw on the bottom shelf of van Grouw’s favorite cabinet, the most obvious mutation is melanism. In short, it is an excess of melanin synthesis, turning a light feather dark, or a dark feather even darker. Sometimes these variants turn out to be advantageous in certain habitats, and these birds are common in some polluted and sooty cities. In the urbanized centre of Lima, Peru, for example, the dark versions of vermillion flycatchers comprise roughly 60 percent of the population.

But in the wild, as in the cabinet, pale variants are more frequently spotted. People tend to call all of these birds “albino” or “partial albino.” In doing so, they ignore the true nature of their differences. In the aptly named “brown” mutants, the synthesis of the eumelanin is incomplete. Without the bold greys and blacks of this pigment, birds are a light brown color and prone to further bleaching by the Sun. Over time, the outermost feathers can turn hoary and even white. The brown down feathers are dead giveaway.

Like watering down a strong cordial, the mutation known as “dilution” leads to a reduction in melanin across the bird’s plumage. The pigment is unchanged, but the colors appear lighter.

“Ino” mutants can still produce melanin, but only in small quantities. Their feet, beaks, and feathers are very pale, turning white as sunlight bleaches them. As in “brown” mutants, down feathers still hold onto the small amount of pigment they have. Their eyes are red, but, with a small amount of melanin, are still functional.

A recent review of published records of aberrant birds in India, conducted by van Grouw and yet to be published, demonstrates the problem. Out of 180 sightings of light-colored birds, 85 were originally considered to be albino. But after studying them, van Grouw concluded that only four had the slightest chance of having this mutation.

To produce an albino, two recessive alleles, or forms of a gene, need to be passed on to offspring, one from each parent. In the rare instance that this occurs, the bird is unable to produce the enzyme that synthesizes melanin. A key stepping stone on the path toward color is lost, and their skin, feathers, and eyes are a devoid of melanin. Their eyes are LED red from the blood that flows through thin vessels underneath the colorless skin. In the wild, they are doomed.

Without melanin, their retinas are pretty much useless. Like a person who wanders into a bright summer’s day from a dark room, albino birds are blinded by the dimmest of light. They are also unable to judge distance. It’s not their conspicuousness that makes them easy pickings for predators, as is often assumed; it’s their poor eyesight. As van Grouw puts it, “It’s not that the cat will spot the bird, it’s that the bird won’t see the cat coming.”

It is incredibly rare to see an albino bird that has flown the nest. But it’s impossible to see a partial albino. “You can’t be partially pregnant; you can’t be partially albino,” van Grouw tells me. A bird either has the mutation or it doesn’t.

And yet there are occasions when a bird’s plumage can be a medley of white and normal feathers. In other words, it is partially white.

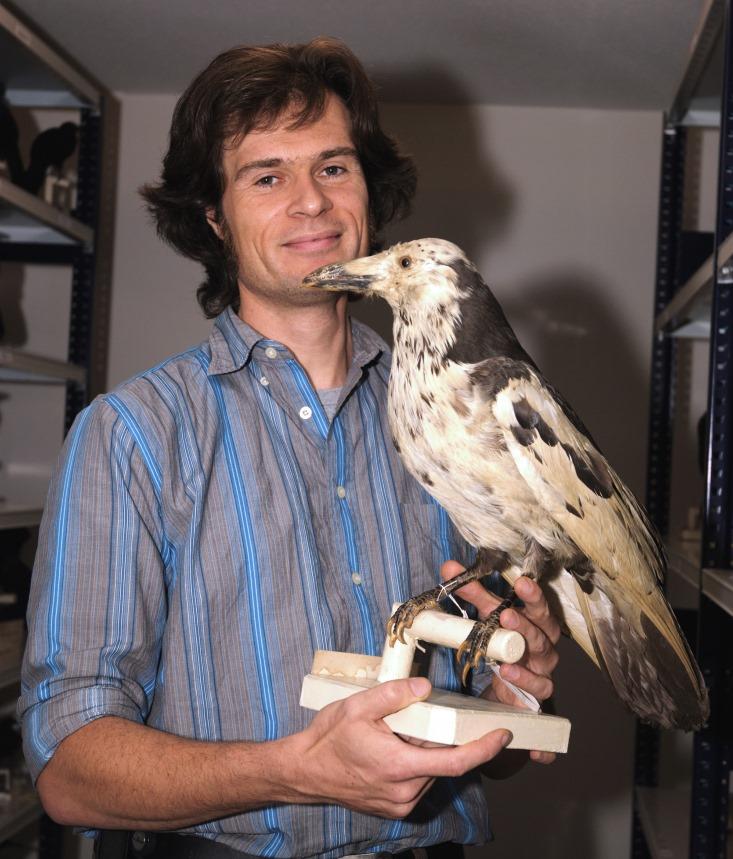

On my visit to Tring, van Grouw shows me his favorite specimen: a white-speckled raven from the Faroe Islands. A recent fledgling when it was collected—but already noticeably larger the ravens and crows I’m accustomed to—its head, belly, and big wing feathers are white. As he affectionately strokes the feathers along its back, van Grouw explains that this bird had an aberration that was common in this isolated population of ravens prior to the 20th century: leucism.

In contrast to albinism, the white feathers of leucistic birds are due to a lack of melanocytes, the cells that make melanin, in some or all of the birds’ cells. In the latter case, the bird’s plumage can be a convincing doppelganger for albinism. But since leucism is exclusive to feathers and skin, vision is unaffected; the cat can see the bird, but the bird can see the cat—and fly away.

These mutations are rare. Although the original Indian records purported to find 30 leucistic birds, only one was a correct identification. The others were probably due to a non-genetic aberration that van Grouw himself shows signs of. As we get older, our hair gets progressively whiter. The same is true for birds. Each molt can bring a paler plumage until, in some cases, the bird looks like it has leucism or albinism.

Back in his office, van Grouw loads some recent scientific papers that have started to use his nomenclature. One describes a leucistic burrowing owl. But, alas, they are wrong. Using their color photo of the “pure white” bird from a vivarium in Rio de Janeiro, van Grouw identifies the “brown” mutation that has been partially bleached over time. “There isn’t a white feather on that bird,” he tells me, gesturing with both hands toward his screen.

It’s nonetheless a start. To establish a uniform nomenclature for the diversity of bird aberrations is hard. To have it accepted by ornithologists is even harder. And yet, one was already in place over a century ago. “They used different names than I do, but that doesn’t really matter… They did distinguish all these different things,” van Grouw says. “Where it all went wrong, I don’t know.”

It seems people today are not the same observers of nature we were a hundred years ago.

Alex Riley is a science writer based in London. He also studies the teeth of sharks and rays at the Natural History Museum. Follow him on Twitter at @riley__alex.