Every few years, a few weeks after a tropical storm, Steve Johnson, a herpetology professor at the University of Florida in Gainesville, gets inundated with calls and emails about an invasion of juvenile toads. They appear out of nowhere and infest roads and people’s garages. And just as swiftly as they come, they disperse. The toads, it appears, wait for the storm to multiply.

Most living entities flee the wrath of a storm, and for good reason. Hurricanes can decimate ecosystems, destroy habitats, and cause loss of life. But as counter-intuitive as it might seem, a few members of the animal kingdom benefit from storms, directly and indirectly. In spite of the destruction and loss, these organisms find a way to make hay while the rain pours.

Toads Like the Rain

Eastern Spadefoot toads get frisky when it pours—and hop out to make love in the rain. Or rather, in the torrential deluge.

Named after the small appendages on their hind feet they use to burrow into the ground, the Eastern Spadefoot toads spend most of their time in the soil, except when venturing out to eat and breed. To avoid predators such as fish, they evolved to consummate their vows in temporary ponds created by heavy rainstorms. “It’s one night of a massive frog orgy,” says Johnson.

When the downpour starts, male toads emerge from the ground making “vomiting-like” mating calls. The females respond, and the orgy runs through the night, after which the females lay thousands of fertilized eggs in the ponds. Most other toads spend a long time looking for mates, Johnson says, so this behavior is quite unique.

Within a few days, tadpoles hatch in such high numbers that the ponds resemble “boiling water” or a “super-organism that’s moving,” Johnson says. The ponds grow algae the tadpoles feed on. Two weeks after the rainy night, tadpoles become toads, hop away from their birthplaces, and burrow into the ground where they await their turn to party. Johnson says the toads are patient and can wait for the perfect mating conditions for months or years.

Dolphins Like the Calm

While hurricanes can kill dolphins, researchers have found that the reproductive success of female dolphins increases after a storm. Animal behaviorist Angela Mackey and her colleagues at University of Southern Mississippi in Hattiesberg, Mississippi, studied bottlenose dolphins in the Mississippi Sound before and after Hurricane Katrina. They found that the number of dolphin calves increased two years after the storm, when compared to the numbers before the storm.

Not only are dolphins who have lost calves likely to reproduce sooner, but Katrina’s aftermath also provided a healthier environment for newborns. The storm destroyed many fishing vessels that would normally disturb the dolphins’ habitat and compete with them for fish. Plus, because they didn’t have to dodge the boats, they had more time to forage, Mackey explains. And while looking food, they interacted more with other dolphins. “Their social networks became more dense and a lot of connections were created between individuals,” says Mackey.

Plovers Like It Barren

Hurricanes can destroy the homes of some species, but also create new places to live for others. Piping plovers—an endangered species of small, sand-colored shorebirds—depend on storms to create their habitats.

“Piping plovers do well in disturbed environments,” says James Fraser, an ornithologist at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Virginia. Hurricanes clear vegetation from barrier islands—long flat stretches of sand found along many coastlines. That’s where plovers like to build nests. The absence of vegetation makes it hard for predators to hide, and lets the tiny birds hop around. Storms also raise underground water tables, which keep the sand moist and full of insects and larvae to eat. Between storms, shrubs and trees regrow, and the plovers’ habitats become worse, says Fraser.

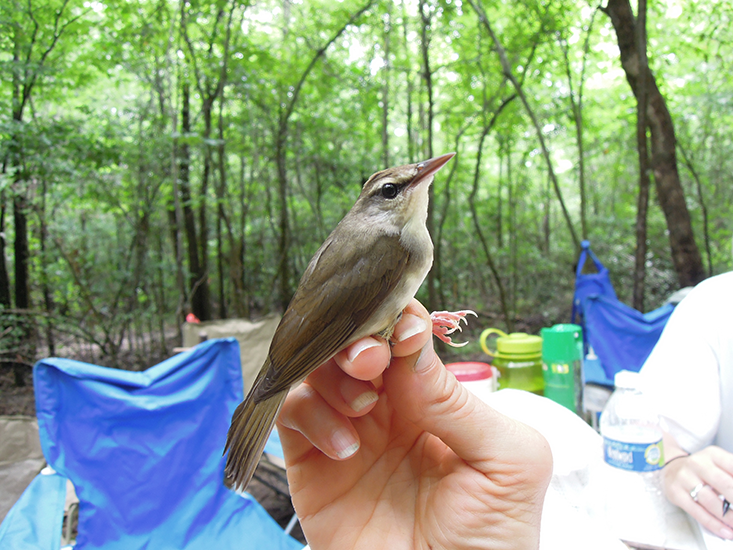

Warblers Like It Messy

Swainson’s warblers are plain-looking songbirds, but their homes are anything but plain. Unlike plovers, who prefer bare living, warblers want it dense—tangled thickets let them avoid predators and raise chicks. They live in bottomland hardwood forests that flood periodically. When hurricanes twist vines and pull down trees in these areas, the warblers get a safe, comfy habitat in which to build their nests. Swainson’s warblers don’t just benefit from such environments—they need them, says Thomas Sherry, a population ecologist and conservation biologist at Tulane University in New Orleans. “When the disturbance ceases, those species often disappear,” he says. One of the reasons another species, the Bachman’s warbler, was driven to extinction was because humans removed or altered the environments that could be naturally disturbed—by clearing land for agriculture and constructing dams, says Sherry.

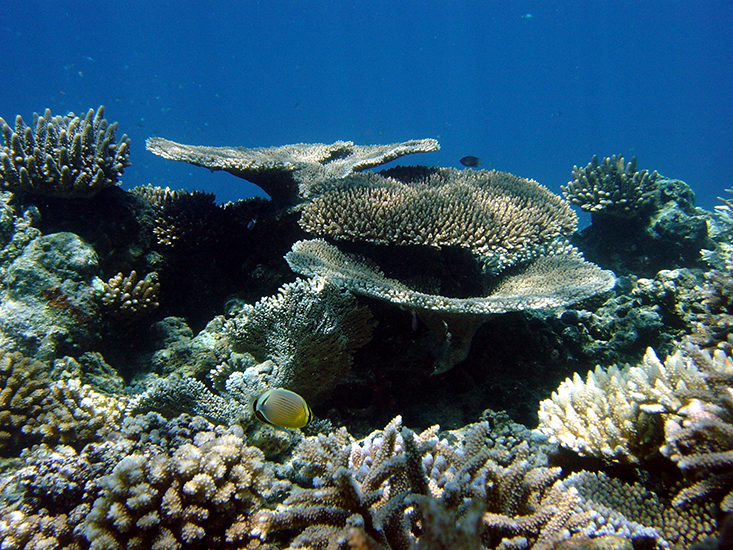

Corals Like It Cool

“Corals would be very happy if they had small storms heading toward them during the summer,” says William Skirving, a researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Townsville, Australia. Ocean surface water, where corals grow, is warmer than deeper water. When it gets too hot, overheating corals eject the symbiotic photosynthetic algae they depend on for nutrients. Corals can die as a result of this process, known as coral bleaching.

During a hurricane, large waves churn the ocean waters, much like a chamber of a washing machine. Warmer surface water mixes with deeper, cooler water, reducing its temperature. “A swell wave of one meter in height slapping up against a reef front can mix water to a depth of 50 meters in one day,” says Skirving. While coral reefs directly in the hurricane’s path can be devastated, those on the sidelines reap the profits of natural cooling.

The piping plover photograph featured in the lead image was originally found on Wikipedia, and was taken by user Tmv23.