With 2015 now behind us, what truly stands out? Other than (alas) holding the record for hottest year in recorded history? Amid a confusion of good, bad, and disturbing news, what I find noteworthy is that 2015 was by far humanity’s best year in space—exploring the universe around us.

How can that be? Even if you happen to be one of those out there who do care about us boldly going, it would seem that our glory days lie far behind us, back in the era of Apollo moon landings. Today’s kids seem mostly to yawn when we turn to the NASA channel or talk about colonizing Mars. The United States spends 0.5 percent of an annual $3.8 trillion federal budget on space endeavors (compared to the Apollo era’s 5 percent). Most of our fellow citizens guess the figure to be much higher, and many think we spend too much.

To those who do care, the romantic stuff—the manned portion of the program—seems to be in perpetual slumber, though we’re promised that may change in three or four years. So, is my raving about a best year in space biased in favor of robots? As a planetary astronomer who serves on the advisory council of NASA’s Innovative and Advanced Concepts group, I know how many wondrous ideas are fizzing forth from creative people. And yes, I’m further fired up by my other main profession—as a science-fiction author.

Indeed, before we’re done here today, I intend to show you that our scientific program to explore the cosmos has produced the most important works of visual art in history.

But first, let’s start with tangible and indisputable reasons why you should care about space. Pragmatic, spin-off technologies like our entire solar energy, micro-chip, and computer industries had their start with NASA, along with the communications satellites that enable cell phones in poor regions where folks could never dream of getting a landline. We take for granted Global Positioning Systems rooted in orbit. Other satellites empower brilliant atmospheric models that have extended the old four-hour “weather report” into amazingly detailed 14-day forecasts, and yearly climate projections that help farmers plan crops and you your vacations.

Oh, and there’s this seldom mentioned “pragmatic” benefit from space. Without spy satellites, verifying arms control agreements, we all probably would have died in some nuclear apocalypse. That, too.

But all of those benefits have been slow and steady. What made 2015 so special?

News from Everywhere

Almost weekly, stunning milestones have come flowing from our faithful robotic probes. Just this year we’ve learned so much about Mercury, Venus, and Earth. Especially Earth where, after unforgivable delays, a wave of scientific satellites like the Orbiting Carbon Observatory are finally nailing down valuable proof of what’s happening to our homeworld-oasis.

But onward! In just the last year, one of our little emissaries orbited and mapped the dwarf planet Ceres, with its weird white spots and possible underground lakes.

Five Mars orbiters have shown us evidence for what happened to that world’s once-rich atmosphere, helping to adjust our ever-improving climate models. They revealed that liquid water still occasionally flows across its surface, as recently as this year. As if that weren’t plenty, at one point those same orbiters swung about to study a comet swooping past the Red Planet, much closer than the distance between us and our moon!

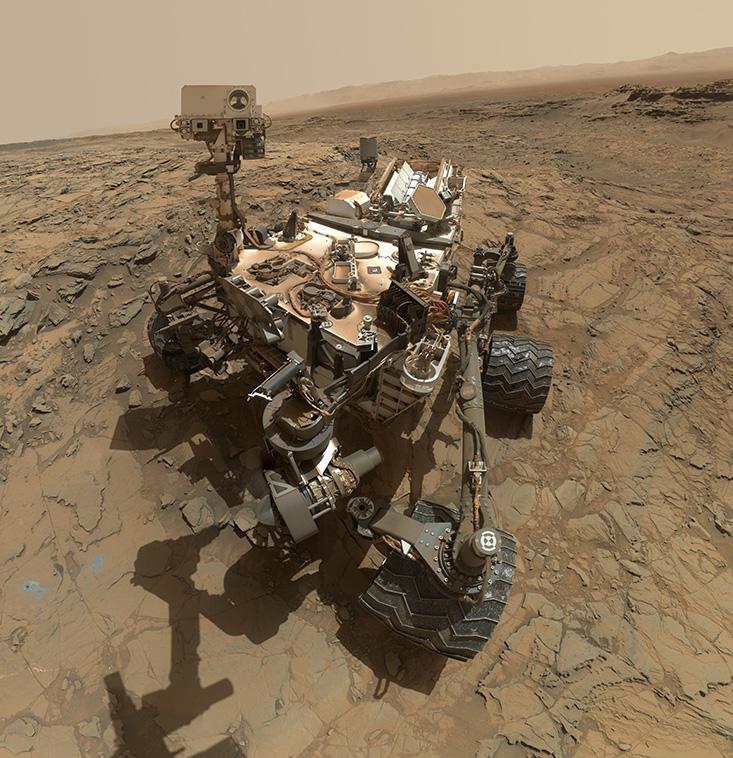

Certainly don’t leave out our stalwart rovers on the surface, Curiosity and Opportunity, chugging along on our behalf, climbing mountains and sifting clues about Martian history going back to when seas rolled across its surface—indicating where some of those waters may still be hiding. And how about another Mars landing next year?

Our scientific program to explore the cosmos has produced the most important visual art in history.

Moving outward, plans were announced for a mission to study the ice-covered seas of Europa and—longer-range—to send submarines diving through methane seas along the waxy shores of Titan. This year, the Cassini spacecraft skimmed close by Saturn’s moon, Enceladus, penetrating plumes from a water volcano and sampling for organic chemicals.

Oh, but don’t neglect the grand achievements of our friends at the European Space Agency, for example, landing on a comet! We learned plenty about how these bodies may transform into asteroids that bold entrepreneurs may plumb for resources. Meanwhile, Japan’s JAXA finally delivered their unlucky Akatsuki probe into orbit around Venus on Dec. 7. Good for you!

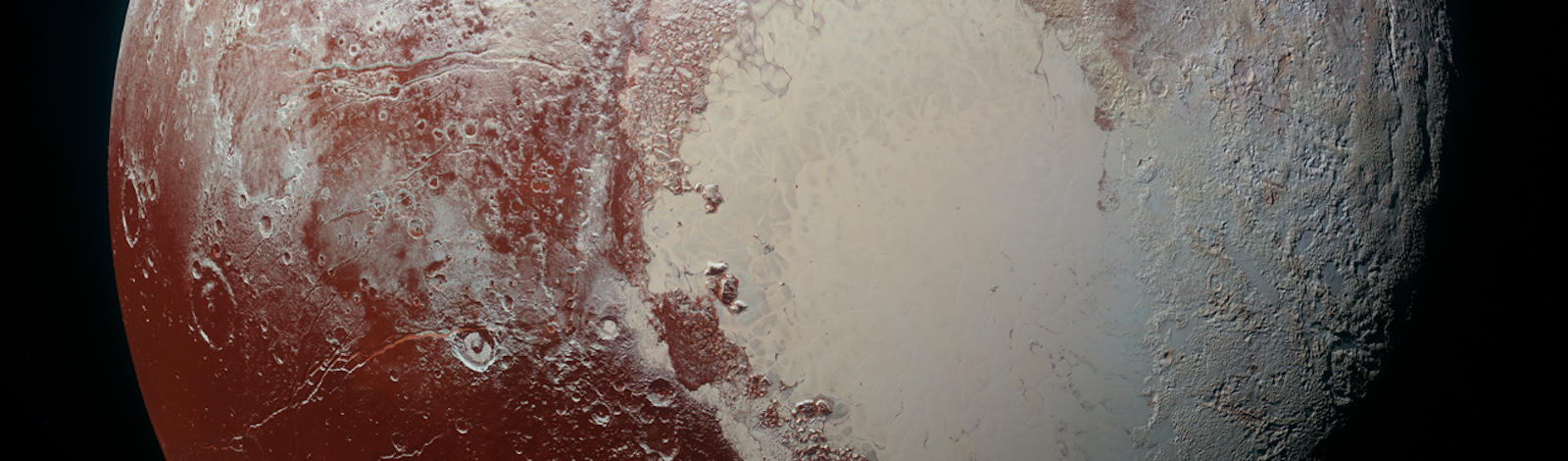

Of course, the capper was New Horizons—launched from Earth so long ago it almost seems another millennium, but finally this year swooping past Pluto. In almost stygian darkness, the New Horizons cameras revealed images of such color and beauty and scientific fascination that even cynics were enthralled. Detailed, data-rich snapshots of the dwarf planet, with its fascinating moon—Charon—and several others, all acquired amid feats of teamwork and skill that had to be (and were) virtually flawless.

Then know that they did it all so smoothly and well that—with the resulting copious fuel reserves—NASA will now send New Horizons 1 billion miles farther, to study an even weirder object in the Kuiper Belt. Hey, that’s darn near interstellar.

Amid all of this, is it worth mentioning that the Hubble Space Telescope and its dozen or so partner craft advance astronomy by leaps, every year? In 2015, studies of vast, intergalactic gravitational lenses seemed to really take off. As we map nearby clumps of dark matter, these clumps bend space and focus light from the most distant portions of the universe, revealing much its earliest days. Progress toward newer, far better orbiting observatories proceeds apace, like a complex system to detect and decipher gravitational waves. The first test-bed for that technology launched in 2015.

On another important front, despite setbacks, the entrepreneurs aiming to improve our access to Earth-orbit have pushed ahead, with Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin sending a rocket to the fringes of space then returning it to land on its tail, re-usable, on the original pad.

Not to be one-upped, Elon Musk’s SpaceX stuck a much more difficult return to launch-site landing on Dec. 21, the winter solstice, opening the way to far-cheaper access to the great beyond.

Meanwhile, Virgin Galactic and others push forward with transformative launch systems of their own, including the improved transport for human beings. Amateur and semi-pro aficionados continue to develop and miniaturize “cube-sat” capabilities, culminating in 2015’s historic deployment of the Planetary Society’s full-scale solar sail test vehicle in orbit. Those two techs, if combined, suggest that deep space will someday be a playground for more than governments and billionaires.

Oh, yes, this is the year that both Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries committed their plans to work with NASA, seeking and developing valuable minerals (especially water) from asteroids.

Is that it? Not by a long shot! I’d go on, except for lack of—well—space.

Go For Profit, Pleasure, and Survival?

I mentioned asteroid mining startups like Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries. Others are trying to go back to the moon. Resources beckon and the upside potential is simply enormous. So much so that just one asteroid of the right kind (if it can be solar melted and smelted in orbit) might provide a sizable fraction of all our planetary economy’s need for metals, allowing us to steeply reduce digging into our mother world’s flesh.

Also propelling a return to human spaceflight will be the disposable wealth of our growing cast of super-wealthy individuals. Selling tickets for suborbital jaunts has already begun, via a number of companies like Virgin Galactic. In my novel Existence, I portray this becoming a hobby industry of prodigious proportions.

But another motive drives our most vigorous space entrepreneurs. While saving our planet must take top priority, there is some wisdom in creating a just-in-case contingency. Colonies on Mars and the asteroids might not only provide wealth, but also a backup for human civilization, should things go sour down here.

Deep space will someday be a playground for more than governments and billionaires.

SpaceX and Tesla pioneer Musk often cites the old saw: “Never keep all your eggs in one basket.” In the short term, of course, any off-Earth colonies would be utterly dependent upon support from home. Over the long haul, though, a thriving solar system civilization is plausible—on paper, at least. As we saw in Japan after the Fukushima quake, even an island of prosperity can need help, from time to time. Earth and her daughters might depend on each other similarly, some day.

This dream becomes more tangible every year. Indeed, it is no less credible than Commodore Perry saying to the Shogun (in effect)—“Let’s be friends. It’s always a good idea to have friends.”

Competence

Calling attention to our space accomplishments in 2015 draws notice to how stunningly effective our hero engineers and space-robot designers have to be, in order to accomplish all these miracles. Tiny errors—on the order of one ten-thousandth of a percent—would have aimed the New Horizons cameras at empty space, instead of snapping perfect images of a dimly lit world, hurtling by far faster than a bullet. Which provokes the question we’ve asked since the space program began:

“If we can do all those things, can’t we solve other problems, as well?”

It may be out of fashion in this era of reflexive, self-indulgent cynicism, but there’s something to be said for the can-do spirit. The notion that “we can solve things!” How else do you explain the spectacular popularity of Andy Weir’s novel The Martian and the subsequent Matt Damon film? Indeed, after decades of flicks that emphasize heroes operating on pure, emotional guts and “instinct,” hunger may be erupting for a different kind of story. One reviewer assessed the joy that some derive from Weir’s book as “competence porn.”

Yes! Now do something else competent. Yes.

Way back during the 45th anniversary of the first moon landing, I recommended an article in Slate, by veteran journalist Joel Shurkin, who covered the Apollo missions way back when. The ostensible topic—what Armstrong meant to say when he set foot on the moon—is actually banal. But Shurkin makes a moving point:

We should explore space because that’s what we humans do … We explore. We are not content with where we are, we want to see what is over there. It is part of our DNA. When the great explorations of Earth began, there probably were people who told Cook and Magellan and Hudson and Columbus and all the rest that it was a waste of resources or that if God wanted us to find a northwest passage, he would have put up road signs or something. But they went. That’s us.

I nod my head vigorously, but also with a modernist quibble. In addition to Cook and Magellan and Columbus we should routinely add in names of other, non-western explorers. Like the Arab wanderer Ibn Battuta, the great Chinese admiral Cheng-ho and the Polynesian pioneer Hotu Matua. Not only is this simple justice—and pragmatically lets you cancel out the “white-male-Euro chauvinist” reflex-accusation—it also shows that you are one of the horizon-spreaders. Always ready to think outside your old, confining box.

Space ultimately is about becoming the kind of people we want to be.

You are someone who’s worthy of talking to others about shattering much bigger boxes. About seeking much wider horizons.

Space ultimately has nothing to do with our insipid political metaphors like left and right. It is about becoming the kind of people we want to be. The kind of people who explore, who look outward, who think that tomorrow can be different. That tomorrow can be better. The kinds of people who will deserve to go out into space.

The kind of folk who might be first—eventually—to go interstellar and find out why the universe seems so silent out there. And perhaps if there’s a problem other species are having, maybe find ways to help. It is that kind of people—who are motivated by confidence, curiosity, and kindness—who deserve to solve the world’s problems. Who can solve the world’s problems.

We are descendants of explorers. Of Enlightenment philosophers who broke with 4,000 years of pyramidal feudal-oligarchies, to say: We’re going to change. We’re going to make the future different than the past.

Apollo May Have Saved Us

I believe the Apollo missions helped to create some of the most important art in human history.

Let me dare to define “effective visual art” as some work or representation that subtly changes human beings just by the sight of it, transforming hearts and minds without verbal or logical persuasion. And by that reckoning, the 20th century featured two hugely effective works of visual art, both of them gifts of physical science!

First, the terrifying image of the atom bomb altered forever our little-boy romantic attachment to war, beckoning us instead to grow up a bit in dealing with this new and awesome power to destroy. Defense became the business of serious grownups. Even (especially) among soldiers, war itself is now seen as evidence of failure—an urgent and risky measure arising out of inadequate diplomacy, preparation, or deterrence. Sure, there were logical reasons to make that shift. But art helped it along. The image of that mushroom cloud seared us. It persuaded, without pallid words.

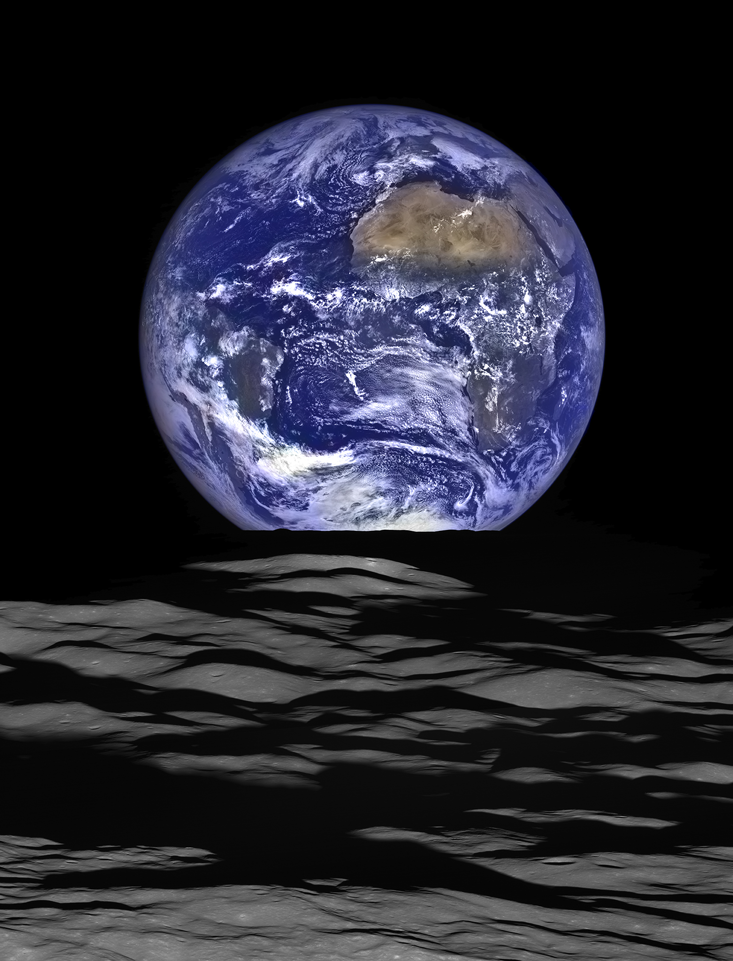

Ah, but then there was the second image that changed us, deeply and forever. That great and transforming work of art was a gift that arrived at the very end of one of the most difficult years any of us can remember—1968—12 crazed and frenetic months that brought most Americans—and most of the world—to the brink of exhaustion and despair. Yes, great music washed over us in a veritable tsunami, as did tragedies, war, invasions, assassinations, riots, betrayals, and fed-up demands for transformation.

Only then, at the very end of that awful year, a final token arrived—like a gleam of hope shining at the bottom of Pandora’s box—when the Apollo 8 astronauts brought home that first perfect image of the Earth, floating as a blue marble in the vast desert of space. A picture that moved all but the most cynical hearts and changed forever our outlook toward this fragile oasis world.

This image—an artwork created by humanity’s curiosity, boldness, and ambition, and the chaste innocent truthfulness of science—transformed us more than anything else. Perhaps making us better, more responsible citizens, and world-managers.

Only now that image has been surpassed in beauty. Even more gorgeous in contrast is the composite image that NASA released on Dec. 19, taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, as it passed about 83 miles above a lunar crater.

I have long wondered when we’ll see another image that so effectively rocks our complacency, convincing us to change. Might it be a sharp spike on a screen of the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence? The appealing face of a robot who has become self-aware? Or perhaps a transformed ape, or dolphin, looking us in the eye and demanding respect?

This year, watching marvel after marvel unfold before us—transmitted by stunningly competent probes and paid for by mere pennies from the average citizen—I realized: It may never again be a single image. With so many things going on at once—dreadful things, hopeful things, and a tsunami of wonders—we must learn to open our hearts and minds to let it all in. Neither wallowing in pessimism nor fizzing with uncritical optimism, but accepting the real lesson. That we can be ambitious and solve problems. We can do.

We can follow many roads, toward helping each other, toward saving our birth-world, and up into the sky. Only by doing it all can we grow increasingly worthy, until that day comes when our children’s children leave cheap, indignant cynicism forever behind, confidently eager to say:

“Let’s go!”

David Brin is an astrophysicist whose international best-selling novels include The Postman, Earth, and recently Existence. His nonfiction book about the information age, The Transparent Society, won the Freedom of Speech Award of the American Library Association. Twitter: @DavidBrin