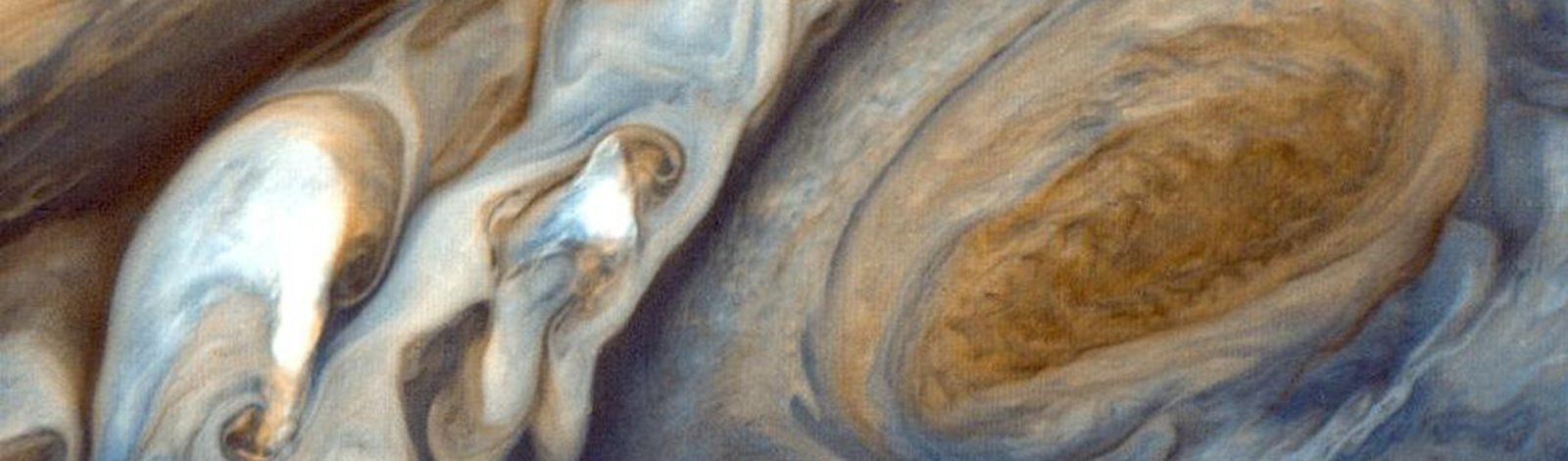

Philip Marcus, you might say, is obsessed with the solar system’s most famous storm. The computational physicist and professor in the mechanical engineering department at the University of California, Berkeley, has been probing Jupiter’s Great Red Spot—a huge, untiring hurricane that takes six days to fully rotate—since the late 1970s, when Voyager 1 began to send up-close images of Jupiter back to Earth.

At the time, Marcus was at Cornell, and when he needed to, as he put it, “unwind, relax, whatever,” he would walk over to a special library, next to the astrophysics building, and marvel at Voyager’s pictures. The storm had raged hundreds of millions of miles away since at least 1665, when it was first observed by Robert Hooke. “I realized that almost nobody in astronomy was trained in fluid dynamics, and I was,” he told me. “And I said, well, I’m in as good a position as anybody to start studying this.”

At the end of this month in Seattle, at the annual conference of the American Physical Society’s Division of Fluid Dynamics, Marcus will address repeated reports that the Great Red Spot is dying. Observations since last spring, of the storm shedding red clouds, seem to indicate its demise. Marcus isn’t convinced. As he told Nautilus recently, “The Spot is not dying.”

What do you find fascinating about Jupiter’s Great Red Spot?

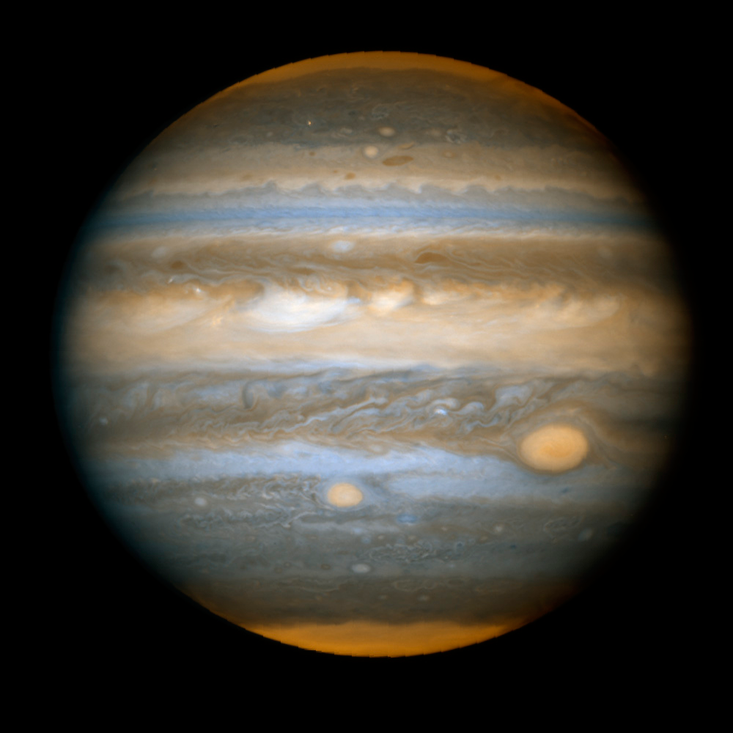

Several things. People have long wondered, why has the Great Red Spot been around for such a long time? The Great Red Spot is a storm, and we are used to storms on Earth. The average hurricane lasts a couple of weeks at most, and it has a definite mechanism for destruction: It either goes into cool water, which cuts off its fuel supply, or it goes over land, which really cuts off its fuel supply. Tornadoes are quite impressive, but they’re very ephemeral—they only last a few hours. So why do we have a Great Red Spot lasting so long? People used to say, “Oh, it’s clouds hanging around a mountain top.” Or “It’s an iceberg in a sea of hydrogen.” Those theories pretty much stopped around 1979, when Voyagers 1 and 2 flew by the planet. Nobody really knew it was a vortex, a huge hurricane that takes about six days for a single rotation. The United States would fit into the Red Spot a couple of hundred times. I mean, it’s really huge. One of the great things about the Voyager missions was that they took hundreds of pictures of the clouds that make up the Red Spot, so we could finally see the whole thing swirling around, and that’s how we knew for sure it was a vortex. Nobody knew it was really spinning.

What has kept it going?

The average velocities going around the spot are about a couple of hundred miles an hour. And the jet streams are also on the order of a couple of hundred miles per hour. But the estimates of the vertical velocities are really, really small. They’re in the order of inches per hour, not hundreds of miles per hour, and because of that, they’ve largely been considered unimportant. But the vertical winds happen over a large area and they happen continually, and therefore we think they can be very important. We think that what’s trying to destroy the Great Red Spot is the heat that is being transferred into the cool top and out of the warm bottom, that is trying to restore radiative equilibrium. But we think what makes the Great Red Spot stay alive despite this radiative heat transfer is this small vertical velocity.

There’s a rule of thumb that as winds descend, they become warm, but as they rise, they become cold. Thermal radiation with photons inside the Great Red Spot tries to equilibrate the temperature of its lid and floor with the surrounding atmosphere. This would tend to make the cold, dense lid hotter and it would eventually disappear, destroying the Great Red Spot.

If we don’t understand how Jupiter works in our own solar system, how can we figure out how Jupiters around other suns work?

But as the heavy lid starts to dissipate, pressure balance is lost. The loss of balance then allows the high pressure at the center of the Great Red Spot to push gases vertically outward through the weakened lid. As the wind rises up, it cools off, due to our rule of thumb, and resupplies cold air to the lid, re-establishing it as a cool, heavy lid. A similar process happens to the floor of the Great Red Spot and in turn re-establishes the warm floor at the bottom that thermal radiation is trying to destroy.

Plus, the upward moving gas that passes through the dissipating lid goes outside of the Great Red Spot, eventually stops rising, and is pushed outward horizontally over an area that is very big compared to the area of the Great Red Spot. It then stops moving outward and descends. That descending gas pushes the atoms and molecules of the atmosphere that surrounds the Great Red Spot downward, greatly lowering their potential energy. Finally the gas completes its journey by returning home to the center of the Great Red Spot. On its final return trip home, that gas harvests the potential energy that was liberated from the atmosphere that surrounds the Red Spot.

The harvest of that energy is what balances the loss of the Great Red Spot’s energy from thermal radiation. In a computer simulation, you can actually measure the direction and magnitude of all the energies that go in and out of the Great Red Spot, and the whole energy budget balances very nicely. You’ve got this great drain of potential energy in the atmosphere in the area surrounding the Great Red Spot due to this circulation of gas, but it’s OK because the sun re-establishes radiative equilibrium in that surrounding area and re-supplies its energy. So, ultimately, the source of energy that prevents the Great Red Spot from being destroyed is the sun.

How did the Great Spot start?

The Great Red Spot probably began in one of two ways: It could have been a large, upward plume that hit the stratosphere and rolled up to produce a vortex. If a rising plume can reach upward to a part of the atmosphere that’s really stable, it will spread outward horizontally, and when it starts to spread out, if it’s in a really rapidly rotating system like Jupiter, the spreading out produces a vortex. The other possibility is that a jet stream went unstable and started a wavy oscillation, and when the amplitude of the wave became big enough, it broke, making vortices that then merged together.

Why did it start on Jupiter and not somewhere else?

Here on Earth, if you fly over the ocean, you can almost certainly tell when there’s an island below you because there’s a cloud hanging on top—topographic features often pin clouds to themselves. But there’s no solid surface on Jupiter until you get down to a very small core. It’s basically a ball of fluid. You don’t have differential heating between continents and oceans. You don’t have winds interrupted by mountain ranges. You don’t have all that messy stuff, so it’s got a really well organized set of jet streams on it. Once you’ve got jet streams, vortices just form naturally. You’ve got winds going in opposite directions, shearing against one another. Think of a ball bearing between two oppositely moving walls. The walls make the ball bearing spin, and the oppositely moving jet streams on Jupiter make the air between them spin. Vortices between jet streams are resistant to anything smashing into them. If I create a vortex in a bathtub and I smash it, the vortex is generally gone. If I do a simulation of a big Red Spot on Jupiter sitting between zonal winds and I smack it, try and break it in two, it’ll come back together. So I think of jet streams as gardens in which you want to grow vortices.

If you want to spend sleepless nights worrying about what could attack the Great Red Spot, think about what could attack its potential energy.

What keeps the Spot together physically?

I am speculating that the Red Spot is, from top to bottom, somewhere between 50 and 70 kilometers tall. From side to side, it’s about 26,000 kilometers. So it’s a pancake. Just like with a tube of toothpaste, if I squish the pancake with high pressure at its center, something is going to squirt out the sides and top and bottom. It’s known that the Great Red Spot has a high pressure at its center, but its gases don’t go squirting out horizontally from its sides because of the Coriolis force in those directions—instead they squirt out vertically from the top and bottom. So, what can prevent the gases from squirting out vertically? The only way that I know to prevent that is if the top of the Great Red Spot has a dense cold lid of atmosphere above it. It’s that extra density that pushes the gases in the Great Red Spot back down. And, below the Great Red Spot, there must be a warm buoyant floor of atmosphere, and that floor prevents the high pressure center from pushing the gases in the Great Red Spot downward and out its bottom. That’s the balance.

So you can do both numerical and analytic calculations and say “Well gee, how dense a lid do I need? How buoyant does the floor need to be to reach that equilibrium?” There’s kinetic energy associated with the winds of the vortex, but there’s also this extra potential energy associated with the cold dense lid above it and the buoyant warm floor below it. While most of my colleagues who study the Great Red Spot are worried about the kinetic energy, I’m like, “No, no, no, guys: that’s only about 16 percent of it.” Most of the energy of the Great Red Spot is in the potential energy of a high-density cold lid and the warm buoyant floor. If you want to spend sleepless nights worrying about what could attack the Great Red Spot, think about what could attack its potential energy.

Why hasn’t friction dissipated the Spot?

Our intuition says that vortices don’t last forever, that there’s always some sort of frictional thing dissipating it. Friction can come in many forms, so one of the things that people thought was a very active way of destroying the Red Spot was by the friction of Rossby waves. Rossby waves are a type of wave in the atmosphere that exist due to the fact that the atmosphere is a spinning spherical shell as opposed to a spinning flat plane, and they’re common in the atmosphere, and move slowly. People thought the Red Spot was going to radiate Rossby waves and these Rossby waves would carry energy with them. When sudden, awful things happen in the atmosphere, like when two vortices collide or something, you see Rossby waves coming out. But generally once a vortex has been established, it shuts down broadcasting Rossby waves so there’s no evidence that the radiation of Rossby waves is trying to destroy the Red Spot, which is actually in a pretty quasi-equilibrium situation.

What else could stop it?

If you want to investigate what could attack the Red Spot and make it disappear, you not only have to worry about what’s attacking the kinetic energy, like friction; you also have to worry about something that turns out to be more important—what’s attacking the potential energy. There’s a well-known reason why the potential energy is attacked: It’s called “radiative equilibrium.” If I were to cool down a region of Earth’s atmosphere, I could pull out my stopwatch and say, “Okay, how long does it take that cool region to warm up and come into radiative equilibrium with the surrounding atmosphere?” Or, if I made a little hot spot somewhere, I could pull out my stopwatch and say, “Okay, how long does it take, by transferring photons and other things, to re-establish equilibrium so there’s no thermal signature anymore of my hot spot?” We know from calculations by other scientists, that at the location in the atmosphere where the Great Red Spot sits, the time for hot or cool spots to disappear is about 4½ years, so that extra warmth or that extra coolness would by then be indistinguishable—gone completely. So we did a lot of numerical simulations and sure enough if you put that effect of warming and cooling into our computer model of the Red Spot, the Great Red Spot just disappears in 4½ years.

What’s the value in studying a far-off planet’s atmosphere?

If we don’t understand how Jupiter works in our own solar system, how can we figure out how Jupiters around other suns work? Finding Jupiters in other solar systems is a very hot topic now, because we want to know if there are other planets out there and if those other planets could harbor life. You have to start somewhere in studying planets around stars other than our sun, and you have to make dumb mistakes. That’s how fields start.

Now I’m going to make a complaint: NASA’s a wonderful organization, and I’m grateful to NASA for the funding that they’ve given me and my fellow theorists. But the amount of money that they spend on hardware—on getting things up into space, compared with the amount of money they spend to analyze the data they obtain from those things is very imbalanced. There are tons of data from the Voyager trips collected 31 years ago that are still unanalyzed, and getting funding to examine them is very, very difficult. People go, “Oh no, you have to do something new and exciting with new data! You don’t want to go back and look at data that is so old.” But there’s stuff there that’s really valuable! What sells in Congress is hardware. Everybody likes hardware. What NASA really needs—I hate to say this—is another Carl Sagan. Carl had a knack for making people appreciate what we discovered as well as the machines that made the discoveries possible.

Brian Gallagher is the editor of Facts So Romantic, the Nautilus blog. Follow him on Twitter @BSGallagher.

Lead photograph by NASA/JPL. This image of Jupiter was captured by Voyager 1. It was assembled from three black and white negatives.

This article was originally published in our “Slow” issue in March, 2015.