I lost my previous husband to cancer when he was 36, followed by my mother. I, too, am a cancer survivor. My husband died six months after he was diagnosed with cancer—after a lung removal, a second thoracic surgery, three brain operations, radiation, and chemotherapy. His suffering was so excruciating that he asked me to do what he couldn’t do for himself after he became paralyzed on one side—he begged me to bring our gun from home and shoot him. His doctors argued combatively in front of us over whether to subject him to more experimental treatments. He died blind, deaf, paralyzed, and half the man he had been in weight.

There was so much wrong with what he experienced. I felt there had to be other ways to address cancer and cancer treatment. I was extremely taken by Azra Raza’s 2019 book The First Cell and her candid portrayal of her life in cancer research and treatment. It was one of the most honest books on cancer I had ever read.

Raza started her career studying acute myeloid leukemia. Today she is a professor of medicine and director of the MDS (Myelodisplastic Syndromes) Center at Columbia University in New York City. She caused a defensive firestorm in cancer medicine with the publication of her book. She took to task the fact that with many cancers, treatments have not progressed past the same standard protocol used a hundred years ago—chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or a combination of the two—what she calls the “paleolithic treatments of slash, poison, and burn.” The side effects of which are pain, toxicity to organs, compromised immune system, the rise of secondary tumors, and, too often, inadequate palliative care, anguish, and death.

Raza has been pressing for cutting the overall mortality rate of cancer by restricting its growth through prevention and early detection—by finding the first cell. She’s built an impressive consensus around the idea of early detection. She put together The Oncology Think Tank with 30 members that include some of the most important institutions and individuals in cancer research. She has not only raised awareness; she has raised millions, $18 million in fact. She’s reached out to over 6,000 biotechnology companies and given over 150 talks in the past year alone. Her plan is to “turn the cancer paradigm from chasing the last cell to finding the first and eliminating it within three years through this coalition and careful scientific research.” I recently caught up with Raza to learn more.

Although your book is called The First Cell, you say cancer doesn’t start with one cell—it starts with two. Can you explain that?

When I was a teenager reading about cancer, what ravished me intellectually was the fact that our bodies give birth to a cell that has found the key to immortality. It becomes a new species. It now follows the Darwinian principles and evolves by natural selection and survival of the fittest. No other life form has broken this code and become immortal. A cancer cell has. I was totally convinced that once we unlock the secret of the cancer cell, we will find the key to agelessness. We can live forever.

For practically 50 years I have been obsessed with the question of how this feat is accomplished by the first cell. Here’s what I have concluded. The first cell does not arise out of nowhere. There must be a stressful environment pushing cells to develop heroic strategies to survive. Change or die. Until one changes. It does not have time to evolve and slowly modify its behavior. It must do a lot very suddenly. One way to do it is to hijack another cell and combine forces to develop into a new species.

This whole idea of the first cell resulting from fusion is similar to what the great Lynn Margulis proposed regarding the fusion of two unicellular organisms to form the first multicellular one. Cooperation rather than competition brought a revolution. After existing as one-celled creatures for several billion years, like tiny bacteria, two of them fused. Now a multi-celled, hybrid creature was born. This First Cell combining two cells has given rise to the millions of animal and plant species we see today. The proof of this symbiotic merger is the presence of mitochondria in our cells. When Margulis first proposed her theory, she was ridiculed and ignored.

I think my brutal honesty might have made me the pariah in the field, but at least it is making people think.

What’s your theory?

I am proposing a similar scenario. Cancer is such a dramatically different cell compared to its normal counterpart that its initiation might involve as dramatic a step as a merger of two cells.

I imagined something like a chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection of the liver. It produces a lot of inflammation in the area. Like wounds that don’t heal. Normal liver cells are being killed in massive waves by the virus. They are profoundly stressed receiving the signal—fight or flight—develop a new survival strategy or die. To escape the horrific, poisonous micro-environment of the liver, the cell needs a hiding place. Where? A new arrival is the blood cells whose job is to engulf and chop up such stressed cells. This is where the union can happen. A stressed liver cell engulfed by the blood macrophage for destruction instead ends up fusing with the host. The liver cell not only manages to survive inside the blood cell, it fuses its chromosomes with those of the host and re-engineers them.

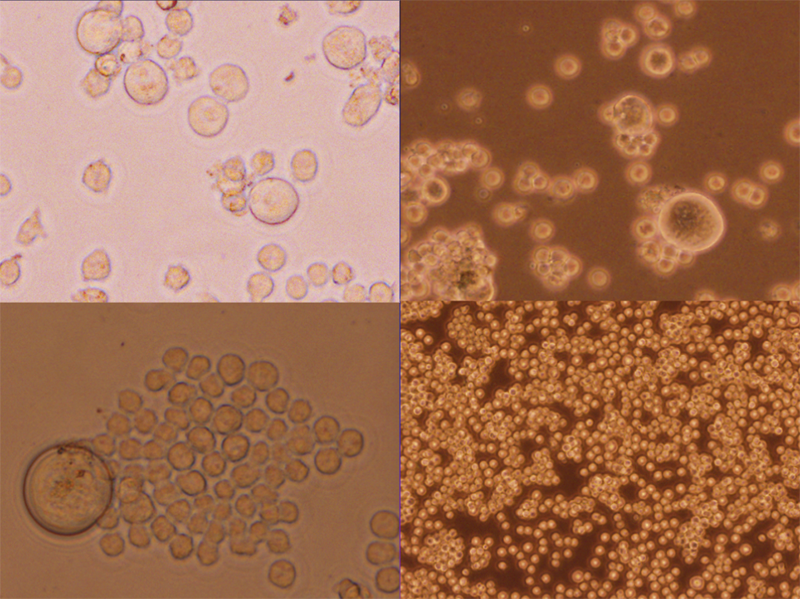

Such a hybrid cell then becomes a giant cell with multiple nuclei and eventually gives birth to a series of smaller cells that stream out and represent the cancer. The early giant cells are reduced to a very few and the vast majority are the smaller cells. When cancer is diagnosed, only rare giant cells are detectable. By studying advanced cancers, we have missed all the early events associated with cancer initiation. If treatment kills off the small cells, relapse of cancer occurs with the appearance of giant cells once again and the whole cycle is repeated. Was there fusion again or did the original giant cells survive?

You write that cancer is “vicious and self-obsessed,” and that it learns to grow faster, stronger, and smarter with each successive division. But do we really know what’s happening?

No. The bottom line is that nobody knows for sure how cancer begins. Some people think it’s one or two genes, at most four or six. Other people think it’s the whole genome, it’s all chromosomes, which contain thousands of genes. Other people think, “No, it has nothing to do with the cell itself. It’s the micro environment, the tissue of field theory.” I mean, nobody really knows. Nobody knows if it starts in one cell, two cells. We don’t know.

What’s the difference between a normal cell and a cancer cell?

The most important differences between a normal and a cancer cell are that cancer cells can evade growth inhibitory signals and continue to divide unchecked, evading the immune system. They can travel out of their organ of origin and land in other organs, a process called metastasis.

So, how does a normal cell take so radical a turn? For all our great investment in research, we can’t answer even the most basic questions about carcinogenesis. To explain how a cancer cell acquires these dramatic malignant characteristics, we urgently need a new way to look at the entire cancer paradigm. The new way is to be less reductionist. And to give complexity its due. Cancer is a spectacularly complicated problem. The first cell does not appear out of nowhere.

Cancer is a silent killer. By the time of diagnosis, there are already millions and millions of cells. We are planning a revolution. A whole new approach is evolving as we speak. We plan to find these first cells by repeatedly screening people who don’t have cancer yet but who are at high risk of developing one. Only after we have caught the cells will we be able to see how their programs differ from normal cells.

It’s been suggested that genomics hold the key to curing cancer. Do you disagree?

It is clear that the model of the 1970s that posited genomics at the center of it all has not provided a satisfactory explanation for cancer’s initiation and expansion. No gene has been identified as a cancer-causing gene, that is, isolated from a cancer cell and capable of transforming normal cells. Mutated genes are found in few cancers, and even within the same cancer, they differ from clone to clone. And if genes were the cause of cancer, why does it take months, years, and decades for carcinogens to cause cancer? It should be instantaneous if a gene is mutated. More recently, mutations in genes associated with cancers have been found in normal individuals. Finally, drugs targeting mutations, with the sole exception for two cancers out of 200 (CML and APL), have not cured cancers. The old model proposing that it is all in the genes is inadequate and misleading. It needs to be replaced.

We should be treating the human body as a machine and monitoring it 24-7 for multiple biomarkers.

What’s wrong with the way we treat cancer today?

Practically everything as far as I’m concerned. What is wrong is that we are waiting too long to find cancer. It’s true that we cure two-thirds of cancers diagnosed today. But how? What are the treatments? Slash-poison-burn. The treatment is brutal and paleolithic. They belong in the stone age. We can and must do better.

The new treatments are targeted therapies and immune therapies. One of the biggest problems is the targeted therapy issue. The idea is to find a genetic mutation in cancer cells and develop a drug that can target the abnormal protein that mutated gene is making. It sounds good, but it’s predicated on the notion of the reductionist 1970s model that I’ve mentioned, that mutated genes cause cancer. After studying thousands and thousands of patients where specific mutations were targeted, it became clear that finding a mutation and having a drug to target it does not guarantee a response. Only a third of such cases responded. Think of it. How good is this match if 70 percent of the time, there was zero positive outcome? And secondly, in the 30 percent who responded, the response lasted for a median of 6 months at most. How good is a 6-month response for a 22-year-old patient dying of glioblastoma, a deadly tumor of the brain? How dare we tell his mother that she should be grateful? It’s an embarrassment. As for immune therapies, they have produced some truly dramatic results. But far too few and at the cost of great physical and financial toxicity.

What are the best therapies and when should they be introduced?

Perhaps both targeted and immune therapies will work best when given at the start of cancer. I am not against developing these therapies. I am asking that equal attention should be given to what are the events in the earliest stages of cancer that can be targeted. After all, the only good news we can give when cancer is diagnosed is to say it was caught early. Stage 1 is not early enough. Cancer should not find us and pose a threat to our lives. We should find cancer first—before it becomes life-threatening. We should be diagnosing it way before Stage 1 and eliminating it at the first cell stage. We should eliminate it with targeted and immune therapies.

I’m hopeful that in the future, we will not even be targeting the first cell but we will treat the stress that caused it to appear. An infection, exposure to toxins, auto-immune-caused-inflammation.

Another thing that is very wrong with how we treat cancer today relates to the screening measures. We perform these annually for five cancers only and look at one cancer at a time. In reality, and with today’s technology, we should be treating the human body as a machine and monitoring it 24-7 for multiple biomarkers from all kinds of compartments looking for all 200 cancers, the so-called Multi-Cancer Early Detection approach. This is not a pie in the sky. It is all happening as we speak.

The cure of cancer is coming and coming soon. It will come because we will make the first cell into the last cell.

What effect has your call to action had on cancer research?

It’s hard for researchers and treatment professionals to give up what they’re doing, even if they agree with my ideas, because the system demands that they continue the same-old same-old. If all the grants are offered to people finding mutations and targeting them, then all of research and clinical trials will be about mutations.

I think that my brutal honesty might have made me the pariah in the field, but at least it’s making people think and question some of what they’re doing. I have no hope that any of these reasoned efforts will change the way business is conducted in cancer. As Thomas Kuhn pointed out, the best way to cause a paradigm shift is to show success of the new one. Once a word processor appeared, no one cared about the typewriter. We have to show that finding the first cell and preventing disease is possible. Then no one will use paleolithic treatments.There are some truly outstanding researchers and scientists, for example, at the Canary Center at Stanford for Cancer Early Detection, who are developing amazing next-gen technologies for early detection. A smart bra, a toilet that traps and examines urine and feces for biomarkers, wearable and implantable devices to sense the disease-caused perturbations associated with carcinogenesis. There are also huge gold mines of data on early cancers that need excavation.

What should cancer-research money be funding?

There’s no dearth of money for cancer research in America. But I am horrified by the mindless waste of huge amounts on animal studies that are meaningless for humans or on doing hundreds of clinical trials focused on the same target with the hope that one will hit a statistical endpoint and reap billions for the company.

How should we start to treat cancer differently?

Be proactive instead of reactive. Monitor wellness to find illness. Monitor people at high risk of developing cancer, like cancer survivors. If you are a cancer survivor, please don’t panic—there’s only a 13 to 18 percent increase in the incidence of a second cancer. Twenty percent of newly diagnosed cancers in America are diagnosed in a cancer survivor. These individuals are attached to institutions where they come for regular check-ups once or twice a year. Our group agreed that obtaining non-invasive samples and banking them could be the key to the first cell. This is what will help us find the biomarkers to look for in early stages of cancer. Surely, the stress to an organ that causes the appearance of the first cell must be associated with a different metabolic signature that can be picked up from the blood or urine or saliva? Our plan is to look for footprints of cancer. The first cell can be detected up to four years before a cancer makes its appearance on a scan and becomes detectable as a tumor.

Is the cure for cancer ever coming? Do you think we will ever be made cancer resistant somehow?

Yes. I say yes with 100 percent certainty. The samples will be game-changers. At last, we will have the chance to sight the happenings at status nascendi. The ability to diagnose any and all cancers with simple blood tests at their earliest stages will change the paradigm. The cure of cancer is coming and coming soon. It will come because we will make the first cell into the last cell.

Right now we are only looking at cancer survivors. Once we find certain markers from these cancer survivors that we think are harbingers of the appearance of cancer, then we can start using the markers in all healthy populations in the country, to see if anyone is going to develop cancer. So, all of this can happen very rapidly as long as we have certain definite markers. We could luck out and find something important in the first year and quickly validate it in a prospective manner, in a small population, bring it to a larger one, and given the capitalist society we live in, you can be sure that it will be immediately picked up and competition will start. ![]()

Gayil Nalls, Ph.D. is an interdisciplinary artist and theorist who pioneered the genre of olfactory art. She is the founder of World Sensorium Conservancy. Follow her on Instagram at @worldsensorium.

Lead art: Valenty / Shutterstock