Human couples could learn a lot from seahorses. The marine marvels spend only quality time together. They flirt, swim together, and mate. The rest of time they go their own way, drifting in ocean currents, leisurely eating their fill. But they do look forward to getting together again.

Right after sunrise, male and female seahorses approach one another, gently rubbing their noses together and then begin to circle each other. Many of them make seductive clicking noises. The partners gracefully rock back and forth, as though to the beat of underwater music. They dance and cuddle together dreamily, as though they’ve lost track of time.

However, love can be dangerous for seahorses. During partner dancing, hormones are released that can make their camouflage fade. This causes changes in color, so their bodies begin to glow, and the contrasts in the patterns of their skin become more pronounced. Researchers hypothesize this is how seahorses signal their willingness to mate.

The marine marvels spend only quality time together.

The partner dances also serve as a means of seduction. Before mating, courtship can take many hours. Finally, the female signals that she’s ready. She swims up toward the water surface, pointing her snout toward the sky, and stretches her body out straight as a stick—a pose that is irresistible to the male. The stallion of the sea presses his chin against his chest and makes his prehensile tail open and close like a switchblade. This enables him to pump water into his brood pouch to show his beloved mare of the sea how roomy it is.

Soon afterward, the mare and stallion of the sea snuggle up together closely and let themselves drift upward. They press their bodies together so that their snouts and abdomens are touching. On account of the curves in their body posture, the space between them looks like the shape of a heart. Then, something amazing takes place. A tubular rod appears in the middle of the female seahorse’s belly, which looks a little like a penis, the so-called ovipositor. At the climax of the love scene, both partners lift their heads as though in ecstasy, curving their backs, and the female seahorse transfers her eggs into the male’s brood pouch, while her partner fertilizes them with his sperm.

Shortly afterward, the loving couple separates. The colors and patterns of their bodies fade again. The male shakes himself to ensure that the fertilized eggs slide into a favorable position in his pouch. His partner usually swims away to go hunting and feeding. However, for the expectant father, the difficult time of pregnancy now begins.

Scientists have long been trying to determine why it’s the males that become pregnant in the realm of seahorses. Only recently have the first explanations come to light.

In 2001, Tony Wilson, professor of evolutionary biology at Brooklyn College in New York, and his colleagues, were able to prove that expectant male seahorses provide nutrition for the embryos in their pouch. In the meantime, it has become more evident how closely the male seahorse pregnancy resembles that of female mammals. For example, the male seahorse’s immune system protects the embryos from infections. Scientists at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel are currently studying the microbiome of the male’s pouch (the symbiotic bacteria) involved in seahorse pregnancy. The expectant father transfers his microbiome to the embryos via his pouch, fortifying his offspring’s immune systems.

Furthermore, the embryos’ waste materials are discharged by the pregnant male, and nutritious, high-energy fats are provided for them. A gaseous exchange enables the embryos to breathe.

The question remains, though, of how the female’s eggs get fertilized by the male. Biologists had assumed the males fertilized the eggs directly in their brood pouch. Yet researchers have discovered a curiosity, at least in the case of the yellow, common, or spotted seahorse (Hippocampus kuda). The males cannot deposit their sperm in their brood pouch because their sperm tube ends outside of it. The long-snouted seahorse (Hippocampus guttulatus) and short-snouted seahorse (Hippocampus hippocampus) cannot fertilize the eggs in their pouch either; it would be anatomically impossible. So how does the sperm reach the eggs?

British professor of zoology William Holt of the University of Sheffield is an expert on seahorse reproduction. He explains that in the case of yellow seahorses, the male’s semen is emitted while mating, but the opening of the brood pouch is around 4 millimeters from the end of the sperm duct. “Hard to imagine how the sperm could swim that far without getting lost in the sea, simply because they’re much too slow,” says Holt. “In the meantime, we presume that while the female is transferring her eggs to the male’s pouch with her ovipositor, she also collects the sperm from the seawater, so it enters the pouch along with the eggs.” Holt considers it very likely that fertilization in other seahorse species takes place in the same complicated manner.

“Collecting” sperm in the water? Very bizarre. Why would seahorses spend so much energy on courtship and mating? Why couldn’t female seahorses simply spawn in the water, like practically all other female fish, and let the males fertilize their eggs in the water by themselves? The reproductive behavior of the yellow seahorse seems illogical and absurd—as though a hunter were to load a rifle, only to throw it at a stag instead of shooting it.

The couples get together daily to greet each other and dance.

Axel Meyer, professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Konstanz in Germany, smiles. Not all processes in nature are perfectly efficient, he says. “Evolution doesn’t begin with a blank page; instead, it makes do with whatever’s already there.” Evolution is not like “an engineer—rather, it proceeds via trial and error.” Organisms have to function in each and every generation, meaning that the evolutionary process is founded on serendipity. “That’s why there are random mutations in the genome, which are passed on as preconditions.” Some things can only change very slowly, and others not at all. There are still quite a few “misconstructions” in nature, says Meyer. Albatrosses have a wingspan of up to 11 feet, meaning they are so heavy that when they land, they sometimes break their necks. “Even the design of human beings isn’t failsafe,” says the evolutionary biologist. “The close connection between our airway and our esophagus leads to the risk of choking to death.”

Darwin wrote about the “survival of the fittest” in 1869, a term he adopted from British philosopher and sociologist Herbert Spencer. “Darwin applies this principle to specimens of the same species,” explains Meyer. “And you shouldn’t let the word ‘fittest’ make you think of a fitness studio.” In nature, the deciding factor is how many offspring a specimen has, in comparison to the reproductive success of its contemporaries. “Fitness is measured as the relative chance of survival and reproductive success of the specimen’s genome in comparison to its competition in the given population.”

Evolutionary scientists, such as Meyer, consider the fact that the opening of a male seahorse’s semen duct is not well positioned as proof that male pregnancy evolved in small steps—and wasn’t planned on the drafting table.

An even greater mystery is posed by the seahorses’ monogamy. Only 3 percent of all mammals have lasting partnerships, and even fewer amphibians, reptiles, and fish do. However, most seahorses are model couples that are never unfaithful to each other. Not only do they have a loving courtship, but they also invest a great deal in their relationship, spending a lot of time together in common activities.

In many seahorse species, the couples get together daily to greet each other and dance. Behavioral scientists assume that the horses of the sea strengthen their relationship with these rituals, whereby sex plays a lesser role. Pairs usually remain together for life. Old tales relate that if one of the partners is caught in a net, the other won’t leave it behind—instead voluntarily following it into captivity. Aquarium keepers recount that after the death of a seahorse, it isn’t rare for the remaining partner to also perish within the next few days. Is it grief that robs the remaining widow or widower of the will to live?

Seahorses’ uncommon reproduction presents another question: It’s the male seahorses that become pregnant, so why don’t the females distribute their eggs among as many partners as possible, like most males in the kingdom of animals do with their sperm? Some primates, dogs, and whales even have a kind of bone in their penis that creates a permanent erection, meaning they can copulate with several different partners one after another. In complete contrast, most female seahorses remain loyal to their partner and do not mate again until their partner has given birth and is ready to become pregnant once more. Why are most seahorses loyal till death?

“In general, we don’t know a lot about the genesis of monogamy in the kingdom of animals,” says evolutionary biologist Anna Lindholm from the University of Zurich. However, it is well documented that the phenomenon independently came into being in several species over the course of evolution. A 2019 study has shown that the activity of 24 genes in the genome of prairie voles, poison dart frogs, and water pipits is strongly linked to monogamous behavior. Presumably, this pattern may also be found in the seahorse genome. Yet this discovery still cannot fully explain the purpose of monogamy.

“One reason that lasting partnerships can pay off is that, in some species, the offspring will only survive to adulthood if both parents care for them,” explains Lindholm. For example, in storks, wolves, and beavers. That explanation may be clear, but it is not valid for seahorses, since their babies swim off on their own after they’re born and aren’t supported by their mother or father in any way. Are seahorses simply more capable of love than other creatures?

Evolutionary biologists doubt that. Yet seahorses do have one decisive advantage due to their monogamy. Pregnant males can be sure they are carrying only their own biological offspring in their pouch, and not any so-called cuckoo’s eggs that were introduced by the competition. In the case of salmon, for example, a second male often flashes by and spawns in the female’s “nest,” after the territorial male, or “official father,” has done so, explains Lindholm. Yet how great is the certainty of a biological pregnancy in male seahorses, if their sperm—at least in the case of yellow seahorses—isn’t deposited directly into their brood pouch?

Could other male seahorses also add their semen? Holt dismisses this. Yellow seahorses’ complicated reproductive strategy does give them a degree of certainty. “When seahorses mate, they’re very close together.” No competitor can come between them. “In addition, the male’s brood pouch closes again after a few seconds, so that no more eggs can be transferred,” emphasizes Holt. “It is neither possible for more than one male to fertilize a female’s eggs, nor for more than one female to transfer eggs to his pouch.” It’s a fair deal.

The main reason many seahorses are monogamous almost certainly lies elsewhere, according to the experts. Most seahorse species live in large, sparsely populated habitats, yet they are slow swimmers and, depending on the species, some of them are very rare.

Offspring will only survive to adulthood if both parents care for them.

“Since it’s out of the question for seahorses to go on long expeditions looking for a mate, any available sexual partner is a valuable commodity, for both the male and the female, and wouldn’t be forgone on a whim,” says Meyer. “Thanks to lasting partnerships, fertile creatures can efficiently pass on their genes despite the low density of members of the same species.” Meyer remarks on the extreme case of the anglerfish in the depths of the seas. In the vast darkness, it is very rare for creatures to come upon other members of their species. If a male deep-sea anglerfish meets a female, he’s not fussy. He immediately attaches himself to the female, in the literal sense of the word. At first, the skins of the couple grow together, and later even their circulatory systems. The male’s jawbone regresses—and eventually it merges with the female organism. In some species of deep-sea anglerfish, the male’s body completely disintegrates, except for the testes, explains Meyer. It doesn’t sound like a dream wedding, but it’s hard to imagine a closer and more intimate relationship.

For love-bound seahorses, “married couples” practice their partner dancing routines daily—as well as their longer wedding dances—ensuring the technically precise delivery of the female’s eggs into the male’s pouch. Experts surmise this also enables them to adjust their reproductive cycles, which are driven by sexual hormones. The female’s next batch of eggs therefore ripens just after her “husband” has finished giving birth to the last brood.

As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome—or to successful reproduction. In fact, not all seahorses are loyal. A restless female Denise’s pygmy seahorse (Hippocampus denise) proved that she was always on the go. Scientists observed her reproductive behavior. This tiny seahorse was two-timing her partners. She danced wedding dances with both of them and mated with both. The biological advantage was that she halved the risk of losing a mate and all her offspring. This calculating seahorse followed the strategy favored by stock market speculators and didn’t put all her eggs in one basket!

Some stallions of the sea are even more promiscuous. Big-belly seahorses (Hippocampus abdominalis), at home in Australia and New Zealand, do not seek lasting partnerships. Instead, they mate with almost any female at hand. That fits in well with the “loyalty due to scarcity” theory of the biologists, since big-belly seahorses live together in a smaller area than most other species.

Many other species of seahorses—romantic wedding dances or not—have a bit on the side in the tumult of an aquarium. If there were sufficient partners available, some male seahorses would mate with up to 25 different females a day. Perhaps a bon mot of Homo sapiens, “morality means lack of opportunity,” also applies to seahorses. ![]()

Adapted with permission of the publisher from The Curious World of Seahorses: The Life and More of a Marine Marvel, written by Till Hein and translated by Renée von Paschen. Published by Greystone Books in October 2023. Available wherever books are sold.

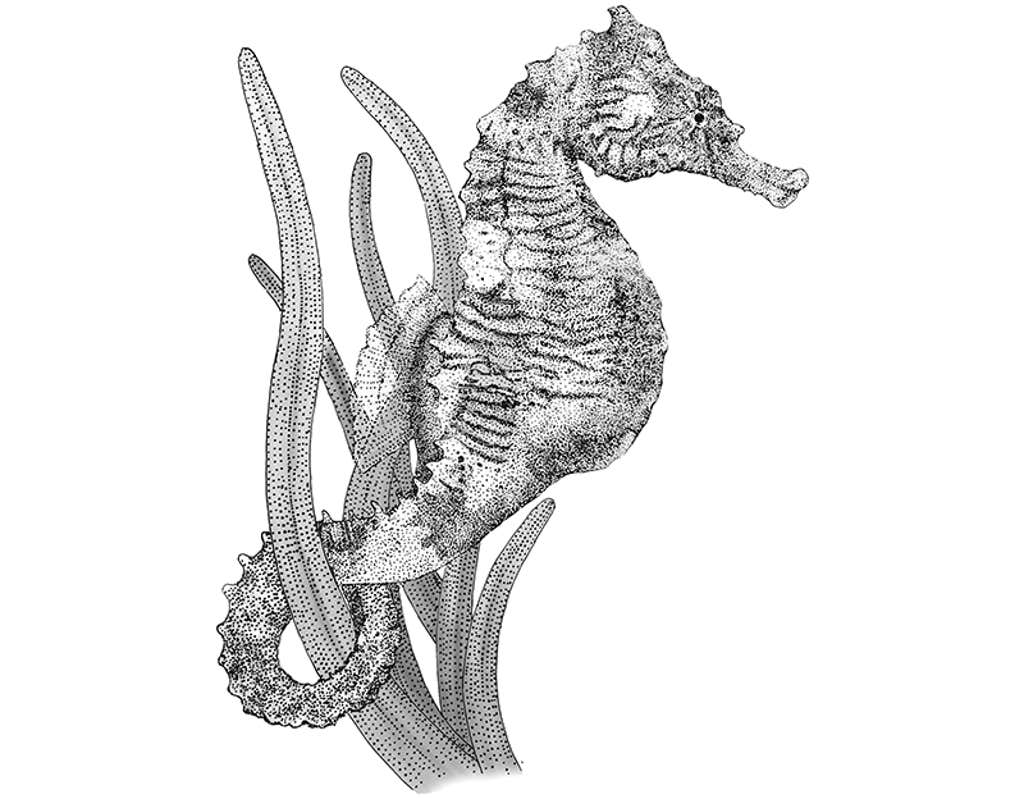

Seahorse illustrations by Roger Hall

Lead photo by Bernard S Tjandra / Shutterstock