In 2020, Japanese scientists had the enviable opportunity of going to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo to examine King Tutankhamun’s “space” dagger. It’s been the subject of conspiracy theories and pseudoscience because the exquisite design, to some, suggests it must be from outer space. The Japanese scientists published the findings of their chemical analysis of the boy pharaoh’s gold-hilted knife in February 2022—a nice coincidence since this year marks the 100th anniversary of the tomb’s historic, perhaps inglorious, excavation. Alas, the dagger wasn’t forged by extraterrestrials—who unfortunately have yet to let us know where they are—but it did come from beyond Earth. Cosmochemist Greg Brennecka, who wasn’t involved in the study, recently told Nautilus that it was made from materials seeded by an ancient meteorite.

Brennecka is a staff scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California, and the author of a new book, Impact: How Rocks from Space Led to Life, Culture, and Donkey Kong. It’s a love letter to his scientific obsession: meteorites. “Meteorites are not just museum relics or interesting items to buy on the internet as physical reminders of the death of the dinosaurs,” he writes. “They represent the origins of Earth and humanity.” Their intrusion on the historical record is no less profound. In Impact, which is buoyed by Brennecka’s amusing footnotes and illustrations, he delights in the many ways meteorites shaped culture, from the creation of Christianity to the pointy accouterments of King Tut.

According to the new research, the amount of nickel and a smattering of sulfur-rich black spots on the dagger, among other features, suggest it was likely forged at low temperatures from a kind of iron meteorite called an octahedrite, for its eight-faced crystal structure. What’s more, the adhesive on the hilt—a lime rather than a gypsum plaster—suggests the dagger wasn’t Egyptian made. There’s hints of a foreign origin, possibly Anatolia. The special knife, analysis suggests, was a gift from the king of Mitanni across the sea to Amenhotep III, the grandfather of Tut. It’s the sort of nifty detail Brennecka would’ve loved to feature in his book.

“It is really great that even with non-destructive techniques, which are often required when dealing with objects like this, we are able to learn tons about how this artifact was made and from what materials,” Brennecka said. “As we are able to investigate more of these pre-Iron Age objects from around the world with ever-improving technology, we will learn more about the technology available to these ancient cultures, who they traded with, and how material from outer space influenced their cultures and shaped their belief systems.”

Brennecka breezily fielded my questions. He was as chill on Zoom as he appears on the page. Because his book is about meteorites and comets, I had to ask about the movie, Don’t Look Up. One anecdote in Impact struck me as an epitome of contemporary attitudes toward science.

At one point in Impact you seem more than a little annoyed about the questions reporters asked during one of Bill Clinton’s White House press conferences. What happened?

Yes. Some researchers found what they thought was evidence of life in a Martian meteorite. If you have a scientific report that shows that life exists on another planet, that’s a civilization-changing discovery. Bill Clinton had a press conference about it, and was saying basically, “OK, some of our NASA scientists have found something really cool. We’re not sure what it is yet. It looks like life, but stay tuned. This is a really exciting time to be living.” And one of the reporters asked about his tie, and one of them asked about Republicans trying to get rid of abortion rights. They didn’t ask at all about the life-on-Mars aspect of the press conference. Man, I just couldn’t believe it when I saw it on YouTube. It was just mind-blowing that that’s what they asked him about. It was depressing.

The apathy of the reporters, how incurious they were, reminded me of the movie Don’t Look Up. Have you seen that?

Yes. It’s funny. And I see the connection, absolutely. It’s like you’re reporting the news, you’re not thinking about the news. That’s a great way to describe it. That’s maybe how the press corps was doing it in Clinton’s administration.

What did you make of Don’t Look Up?

I thought it was fantastic. I think it’s probably more pointing toward global warming than it is an actual meteorite impact, or a comet in their case, but I think it’s a very well-done movie of people not really paying attention when they don’t want to pay attention to something, sticking your head in the sand and not looking up. It was interesting, funny, depressing—all the words. The internet allows people to go into their own little corner of the internet, and not really pay attention to the big-picture stuff. I think that has a lot to do with politics nowadays, and just how we’ve gone as a country and world. The internet is probably the one thing you can easily point to to “blame” for that type of human behavior. It’s scary.

So what’s the scientific community up to now in terms of preparing for a potential big impact?

A lot of it is how much time we have. In Don’t Look Up, there was very little time, six months or something. If we’ve got six to 10 years, then that’s a different story. Then we have a lot of different options, because moving an asteroid or comet’s trajectory toward Earth is possible in a lot of different ways, and it’s a lot more possible if you’ve got a lot of time. And if you’ve got a lot of time, then you can do things, like park a spacecraft next to it. You can use the spacecraft’s gravity to move it, the gravity-tractor method. There’s people that say you could paint one side of the asteroid white so you get a lot of different behavior from the sun’s rays, so it would slowly shift its trajectory. If you don’t have a lot of time, you’re pretty much going the military route, Armageddon-style or whatever they were trying on Don’t Look Up.

We are preparing for these types of things. NASA and the European Space Agency just launched the DART mission. It’s basically trying to redirect an asteroid if it is on an Earth trajectory. It’s going up there and running into it and seeing how much it actually changes the trajectory of the asteroid based on that impact. If we had to do this for real, we would use larger conventional weapons, or nuclear weapons.

Let’s back up. How did meteorites shape ancient Egyptian culture?

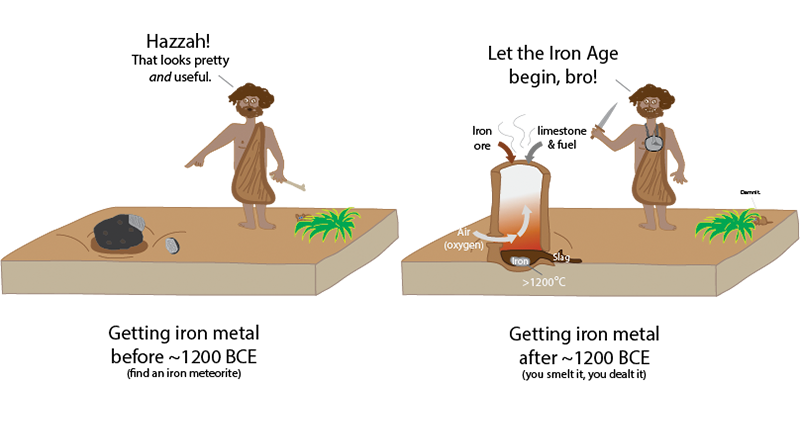

The Egyptians were big into looking at the sky for probably a variety of reasons. There was obviously no light pollution, and they could see things very well. Ra was their sun god, so they clearly had a lot of connections to the sky and looked at it as kind of a religion. But they also were probably fortunate enough to see a couple large meteorite falls. Ancient Egyptians weren’t able to smelt iron into a metal form, so if they were to see a meteorite fall and go collect it, it would be a shiny metal that they’ve never seen before, and also have a lot of important properties that you want in a metal—good for stabbing, hammering, or whatever—and they certainly couldn’t make that metal. It’s really rare, and was found in a lot of different tombs of some of the pharaohs. King Tut had a knife that was made from meteoritic material. It’s a really sweet-looking knife. But they clearly treated it as a very important metal, and they gave it its own hieroglyph, about “iron from the sky,” which is what it directly translates to. That in itself tells you that they knew where it was coming from, that it was something special that wasn’t just laying on the ground.

Do we owe the early spread of Christianity to a meteoric airburst that Saul thought was a sign from Jesus, which convinced him to convert and start evangelizing?

Yes. There’s pretty good evidence that there was a sky event. You look at the stories that we’re told and they match up very well with what actually happens in a meteoritic airburst, down to the medical conditions that Saul had, which was basically some blindness for a few days, and then there’s a peeling off of the eyelid. If the historical documents are correct, that’s what was happening to him. Paintings of the time showed him being knocked off his horse, people being knocked down. There was something that happened at that time and it matches up pretty well with what we know has happened in recent times with things like Chelyabinsk, which was a meteorite airburst, as well as a meteorite in Siberia about a decade ago. There’s quite a bit of connective evidence to suggest that Paul changed his tune because of a meteoritic airburst. It’s crazy how religions develop. I was certainly surprised at how many of them had connections to the sky and meteorites.

The way planets develop is also pretty crazy. What was Earth like when it was only around 150 million years old, and how did it change when it got slammed by a massive rock called Theia?

Earth was just getting started. About 150 million years after the solar system formed, we don’t have a great idea about what Earth was like. There’s a lot of speculation as to what the atmosphere was like and what the surface was like, but what happened is that we had a meteorite the size of Mars hit Earth, and you had this obviously massive impact which created this cloud of rock vapor, basically, which is what the moon eventually formed from. Before that we were on a similar trajectory as Venus. Venus has a very crushing atmosphere. The surface is really hot. It has 96 percent CO2, so it’s basically unlivable. When that meteorite impact happened that formed the moon, it erased the atmosphere that Earth had developed at that time. So it hit the reset button, which was really beneficial for Earth in the form of life, because life doesn’t really exist in conditions that Venus provides. Think of taking off a winter coat. I think that’s how a lot of people view it at this point.

You write that space rocks led to Donkey Kong. How so?

It certainly requires a lot of high-end equipment to make something like Donkey Kong, and we wouldn’t have those metals if it wasn’t for meteorites landing on the planet. When the Earth originally formed, it was a molten ball of rock. Things like palladium and gold that are used in high-end electronics go to the core and we wouldn’t be able to access it at all. The only reason we have those types of metal that we actually mine and use in high-end electronics is because meteorites have continued to land on Earth after it was a molten ball. Once you form that crust of Earth, the metal from falling meteorites doesn’t make it to the core after that. They basically stay in purgatory and are cycled around in the crust, and that’s why we end up with ore deposits of nickel and gold that we exploit for various purposes. So, we wouldn’t have electronics—and video games—if we didn’t have meteorites.

Are scientists persuaded yet that life arose from stuff in space rocks? You say that major components of DNA and RNA are embedded in them.

I don’t think anybody seriously believes that life arrived on meteorites, but the ingredients arrived from meteorites. There’s very strong evidence for that. Just the sheer amount of organic, well, biologic precursors that are contained in meteorites and the amount of material that is arriving on a daily basis not only now, but particularly in the early solar system, is kind of mind-blowing. All of the biosphere that we have could have easily arrived from meteorites within the first 500 million years of Earth. It’s just remarkable how much stuff is actually pelting Earth with biological precursor materials.

Do we know whether life might have arisen on Earth if there were no space rocks bearing biological material to bring it there?

No, but it’s one of those things that without the raw ingredients, how do you get there? You need materials possibly semi-assembled before you’re going to make that jump to life. It’s important that we had those raw materials to start with, and also the fertile ground, basically, of the early Earth, where you had a reduced atmosphere that provided a lot of energy that early life could utilize.

You write that when one realizes that Meteor Crater in Arizona is not considered a very large crater on Earth, “this becomes just a tickle scary.” Why is that?

Well, I don’t know if you’ve seen pictures, or been to Meteor Crater, but it’s a gigantic crater. And you stand at the rim and you look out there and you go, “Holy cow.” To be near this when it happened, it would just be devastating. And then you just go, “OK, well, the size of the rock that hit here is somewhere around the size of a school bus,” and that’s not that uncommon. And when you look at major mass extinction events, we’re talking about thousands of times larger than what formed that crater. That’s scary to think, if a rock smaller than a school bus could make that big of a hole in the ground, how big of a problem would it be for Earth if you had something twice that size or larger?

Tell us a little bit about the academic hubris that was going on during the Enlightenment that led researchers to dismiss even contemporaneous accounts of meteorites falling.

It’s kind of depressing, actually, because you like to think science is above this type of stuff sometimes. For the people that were saying, “Oh, this giant fireball happened in my backyard, and here’s a rock from it,” that seems like a very fantastical type of thing. During the Age of Reason and more scientific thinking like the Enlightenment, it’s easy to cast that aside: “Well, you’re just making that up.” And that’s frustrating, because this was happening multiple times with a lot of different cultures in a lot of different places where everybody’s telling similar stories of fireballs making a large bang, and people that had nothing to gain from these types of stories are just telling what happened. It took a few very careful scientists to document these types of things and a couple well-timed falls to make it really stick in the academic community that these are actually things coming from outer space.

Why do you describe your time dating the ages of Martian meteorites as near and dear to your heart and a little traumatic?

It’s really difficult. I worked on one of these meteorites when I was a postdoc, trying to determine when it formed on Mars. And what is required is you have to pick a bunch of different minerals and separate all the minerals out into their own little groups, light stuff versus dark stuff versus medium stuff, all the similar minerals together, and you have to do it under a microscope with a little tiny pair of tweezers, or a little piece of fiber that you can separate these minerals with. It’s just a lot of painstaking work. I listened to a lot of books on tape when I was doing it. It was six months worth of work to get one number, which is a very important number, and I’m not saying it’s not, but man, it was a lot of work.

What was the number?

It was 570 million years old. It was a rock that formed on Mars about 570 million years ago, then was blasted off of Mars and then crossed Earth’s orbit and landed in Morocco in 2011, I believe.

Morocco, you say, is one of the best places to hunt for meteorites. What are some other good spots?

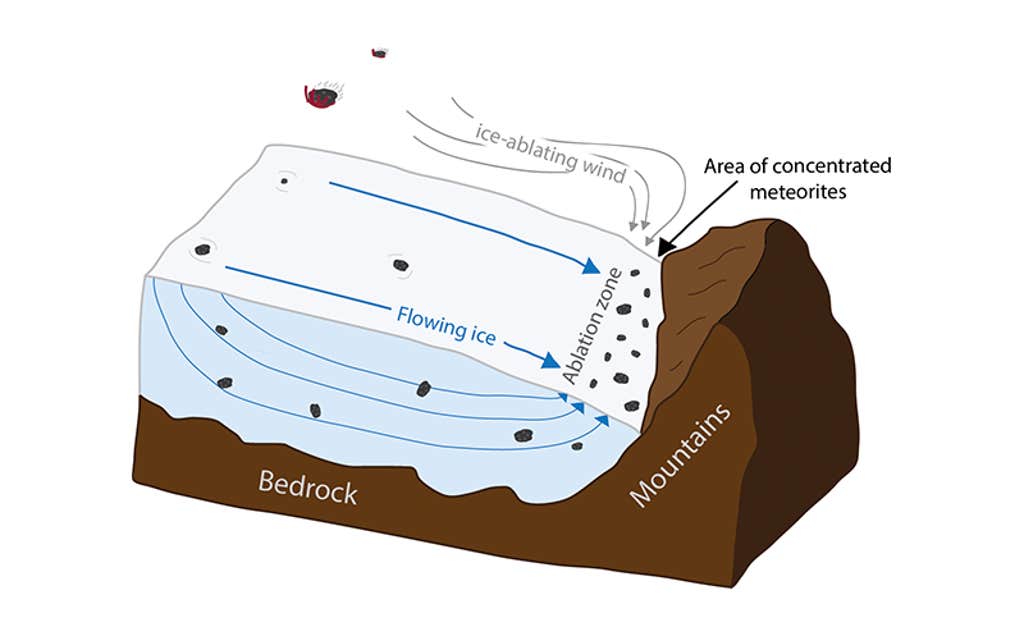

Certainly areas that don’t have a lot of rocks to start with. It’s pretty difficult to actually tell if a rock just laying on the ground is a meteorite or not unless you’re pretty well-trained, and I would say even most meteoriticists have a hard time sometimes. So just having a lack of other rocks is very important. Places like deserts, dry lake beds—those are really important places for people to go look for meteorites. And, of course, glaciers are the classic one that people go down to Antarctica to collect, because if something’s sitting on top of a glacier, it probably came from the sky. ![]()

Brian Gallagher is an associate editor at Nautilus. Follow him on Twitter @bsgallagher.

Lead image: klyaksun / Shutterstock