In

the summer of 1867 American photographer Carleton Watkins hauled a

mammoth wooden camera through the wilderness of Oregon, taking

pictures of the mountains. To prepare each negative, he poured

noxious chemicals onto a glass plate the size of a windowpane and

exposed it while still wet, developing it on the spot. Even then, his

work was not complete. Because wet-plate emulsions are

disproportionately sensitive to blue light, his skies were

overexposed, utterly devoid of clouds. Back in his San Francisco

studio, Watkins manipulated his photos to resemble the landscapes

he’d witnessed. His finished prints were composites, embellished

with a separate set of cloud-filled negatives.

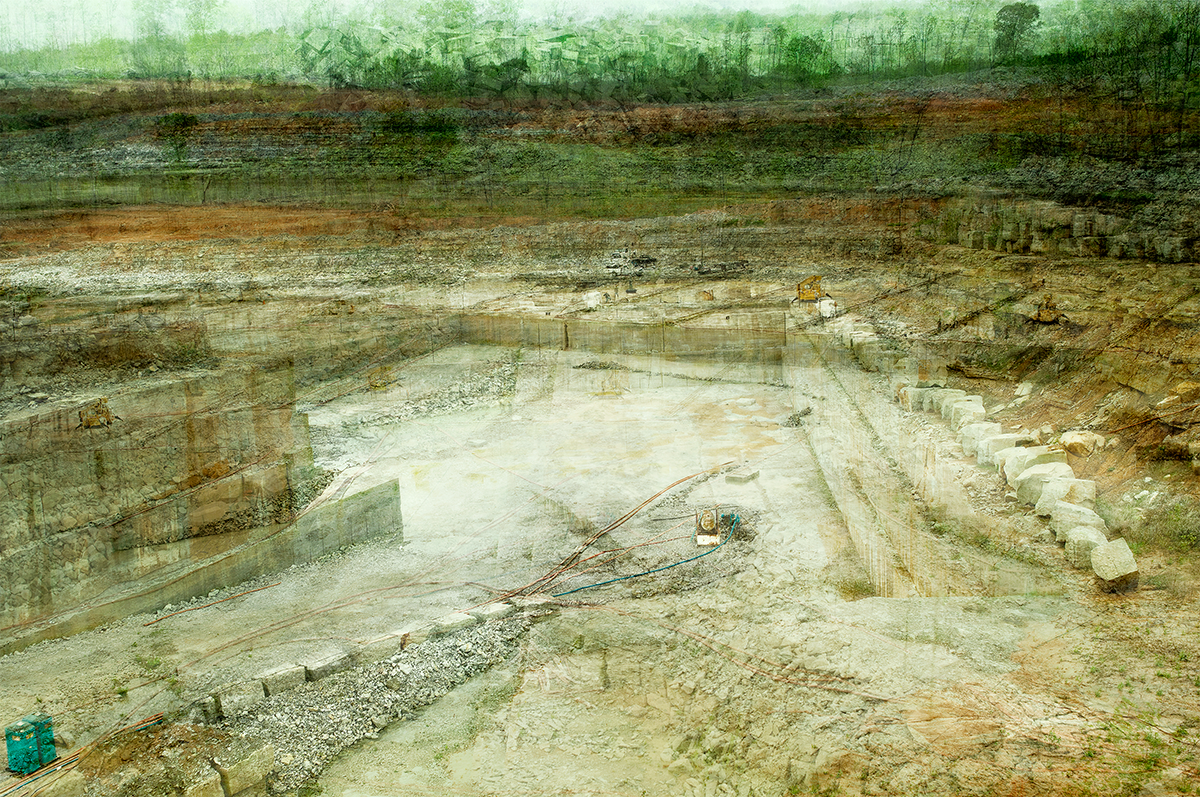

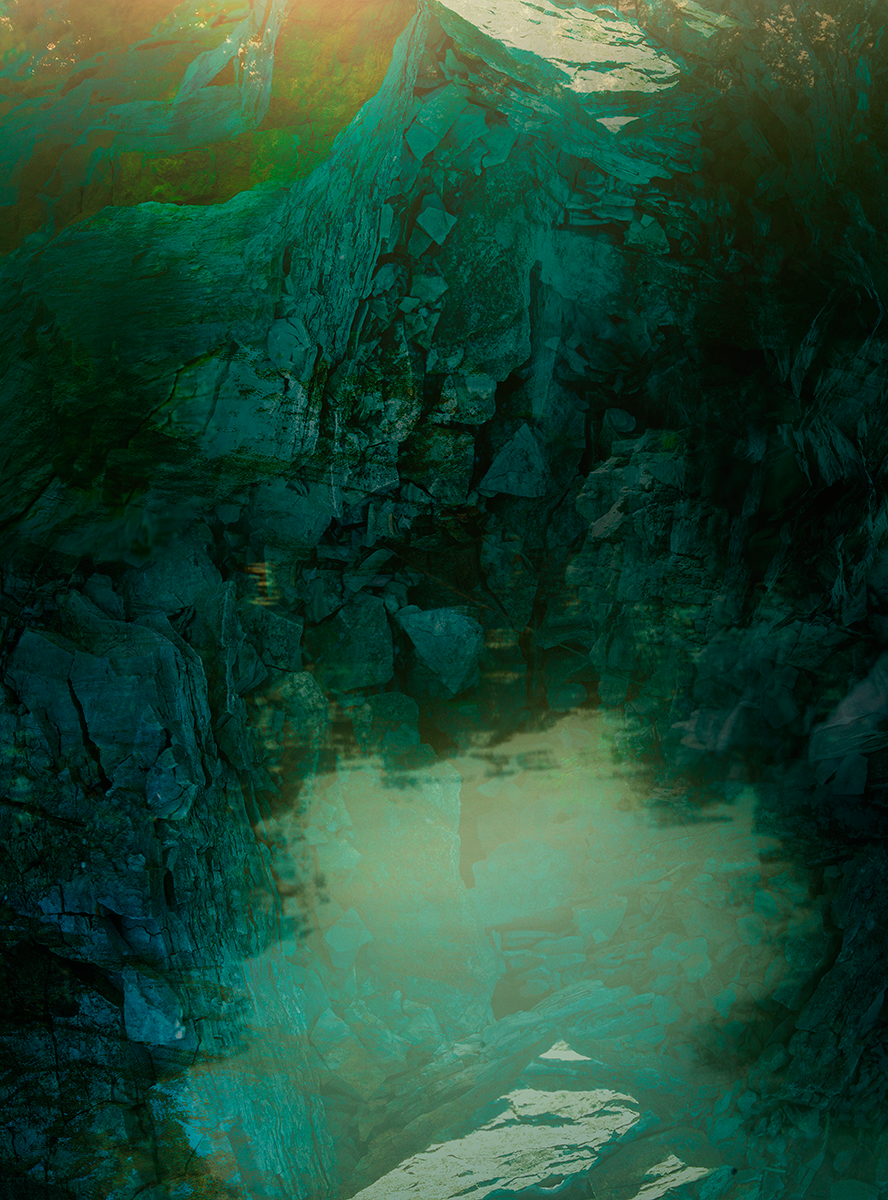

Nearly a century and a half later, Elena

Dorfman—another American photographer porting a large-format

camera—spent several summers in the rock quarries of Kentucky and

Indiana, landscapes as dramatic as Watkins’s Oregon. Dorfman had

none of the old limitations. Her digital Hasselblad instantaneously

captured 32-megapixel photos in full color. But it didn’t satisfy

her. In postproduction she created composites on her computer,

layering as many as 300 images to obtain effects unlike anything seen

in nature.

In one sense, Dorfman

was doing the opposite of what Watkins achieved with his library of

clouds. While his intervention made the mountain vistas more

meteorologically accurate, she

intentionally

introduced physical impossibilities,

from conflicting perspectives to rearranged geology, much

as a painter might fictionalize a scene. Yet

in another sense, each photographer was artfully striving for truth

about how we experience the natural world, laboring against the

inadequacies of the camera. For Watkins, the constraints were

physical. For Dorfman, they’re neurological, a discrepancy between

photomechanical depiction and how the brain processes what the eyes

perceive. Like many modern artists, she has a strong intuitive grasp

of how the visual brain works and understands that her pictures can

be made more stimulating by seeding them with conflicting

perspectives.

Examining Dorfman’s trickery—and the artifice

of other photographers from Weegee to David Hockney—provides a

valuable way of learning about how the brain handles contradictory or

uncertain visual information. Equally important, the neuroscience of

vision helps elucidate what makes these photographs so artistically

compelling. Enlisting photomanipulation, these photographers achieve

one of the most oft-praised qualities in art—ambiguity—in ways

that neuroscience is now beginning to understand.

Dorfman intentionally introduced physical impossibilities, much as a painter might fictionalize a scene.

In a 2004 paper titled Consciousness

and Cognition,

University College London neurobiologist Semir Zeki argued that the

brain experiences ambiguity as the “certainty of many, equally

plausible interpretations,” much like an optical illusion

alternately seen as approaching and receding. Zeki holds Johannes

Vermeer’s paintings as supreme examples of artistic ambiguity,

citing Girl with the Pearl Earring

to support his aesthetic judgment. “She is at once inviting yet

distant, erotically charged but chaste, resentful and yet pleased,”

he writes. And, as Zeki notes in his 1999 book,

Inner Vision,

Vermeer’s art is widely admired because the artist is able to

express all of that “in

a single profound painting, profound because it is so faithfully

representative of so much.”

Too bad Vermeer didn’t have a camera.

Photography may be more suited to capturing multiple conflicting

certainties than painting. A

painting can only blend visual information that has been preprocessed

by the unreliable brain. Each photograph, on the other hand, is an

independent fact. In

layering them without resolving their contradictions, as Dorfman

does, photographers approach the tenuous internal quality of truth.

On the surface,

photographic

ambiguity

is an oxymoron. The camera sees the

world with total fidelity to physical laws. It’s a deterministic

system, the performance of which can be perfectly predicted, given

the optics and the chemistry or necessary electronics. Human

perception is far messier, hacked together by a visual system riddled

with inconsistencies, as Zeki documents in Inner

Vision. Perception

is a product of evolution rather than engineering. Nobody thought out

in advance how all the parts would work together. It

isn’t really a system so much as a Rube Goldberg contraption where

the parts just manage to interact. For

instance, every eye has a blind spot where the optic nerve passes

through the retina, carrying signals to the brain, yet this blind

spot isn’t noticeable to the viewer. As National Institute for

Physiological Sciences neurophysiologist Hidehiko

Komatsu details in a 2006 Nature

Reviews Neuroscience review, the brain

fills in the blank in what is perceived by interpolating visual

information from areas of the retina surrounding the hole: The

resulting sight is an approximation.

In layering images without resolving their contradictions, photographers approach the tenuous internal quality of truth.

In fact, most everything about how we see comes

down to heuristics. In a 2005 Nature

paper, Harvard neuroscientist Patrick

Cavanagh observed that “our visual brain uses a simpler, reduced

physics to understand the world.” In other words, we aren’t using

all the complex mathematics of textbook optics to analyze the

relative position and characteristics of objects. We’re taking a

few imperfect cues and improvising. The visual information isn’t

totally accurate, but it’s good enough to get by and can be more

useful than perfect knowledge. (You don’t need to calculate the

velocity of a falling rock to know that you should step aside. In

fact, if you start making measurements from where you’re standing,

you probably won’t survive to complete them.)

Painters have an intuitive grasp of these

heuristics, taking visual shortcuts such as showing more of an object

than can be seen in a single glance or muddying insignificant

background details.

Those distortions

and uncertainties make their pictures less true to life but more true

to us: They reflect how we see. On

that basis, Cavanagh claimed that “artists act as research

neuroscientists,” informing us about how the brain works.

That may be inevitable for painters, since their

paintings derive from the perceptual apparatus of their own eyes and

brains. The heuristics of the mind guide the naive hand. The reduced

physics can be circumvented only with intense effort. For instance,

achieving unflawed one-point perspective, in which all objects recede

to a single vanishing point (like a converging set of railroad

tracks) requires rigorous training in overcoming the eyes’ constant

movement and refocusing. A geometrical system must be superimposed on

the canvas, and even Renaissance masters were notoriously hazy about

the correct projection of shadows. Photographers have the opposite

problem. One-point perspective comes in the box. The camera’s view

is too absolute. To be neuroscientific—and to

make pictures that resonate in painterly ways—photographers must

actively emulate the distortions and uncertainties inherent in vision

by purposely making their pictures deformed or ambiguous.

Distortions and uncertainties make their pictures less true to life but more true to us: They reflect how we see.

In 2006 MIT neuroscientist Pawan Sinha and

colleagues showed that faces with exaggerated features are more

immediately recognizable than straight depictions—despite being

less accurate—because they deviate more from average human

appearance. Paradoxically, you increase the intelligibility of the

image by decreasing the verisimilitude. Pablo Picasso instinctively

exploited this phenomenon by selectively distorting facial features,

intensifying the presence of portrait sitters such as Gertrude Stein.

In the mid-20th century, the American photographer Weegee applied a

similar tactic in his caricatures of public figures, including Lyndon

Johnson and Marilyn Monroe, whose features he twisted by physically

warping his negatives and using trick lenses. Johnson’s sloping

nose was obscenely elongated; Marilyn’s luscious lips were puffed

up to become positively lascivious.

Ambiguity has also taken cues from modern

painting. David Hockney, a painter by training, has revisited Cubism

with a camera in photo collages constructed from dozens of snapshots.

The snapshots are all close-ups of the same subject—say, a city

street or a swimming pool—each taken from a different angle and all

overlapped to render the contours of the original scene inexactly. As

in a Cubist painting, no single point of view can account for all the

visual information. Yet the ambiguity about where you’re standing

and the uncertain positioning of the scenery don’t make the image

confusing: They make it all-encompassing.

Visual research by Harvard neurobiologist

Margaret Livingstone and colleagues helps explain why Hockney’s

method works. When

we encounter an unfamiliar setting, our eyes dart around, acquiring

snapshots of everything in sight

before we begin to analyze what we’re seeing. This tactic maximizes

our acquisition of information before we know what we want to know

and prevents us from prematurely filtering out details that may later

prove important in terms of how we handle a crisis. But as a

consequence, each snapshot is independent. That means that, while

we’re looking, we aren’t aware of any inconsistencies between

images. Evolutionarily, noticing discontinuity simply wasn’t

important. As Livingstone and Wellesley College neuroscientist Bevil

Conway wrote in a 2007 review in

Current Opinion in Neurobiology,

“Perspective and reflections change second to second as we move our

eyes across a scene. Therefore, there would have been little

biological benefit to incorporating the rules for global perspective

or illumination into our visual computations.” Hockney’s photo-cubism embodies and

exploits our obliviousness to show us more than can possibly be

captured with the camera’s one-point perspective. We have the sense

of being right there with him.

When we encounter an unfamiliar setting, our eyes dart around, acquiring snapshots of everything in sight.

Dorfman’s layered photographs work on the brain

in a similar way, though they have less in common with Cubism than

with the post-Impressionist paintings of Paul Cézanne. Instead of

kaleidoscopically fragmenting the picture plane, Cézanne fused the

visual information gleaned from multiple disparate perspectives. In

his still lifes, for instance, a bowl of fruit might be shown at an

impossible tilt that allows you to see all the apples and

the bowl’s contact with the table. The reduced physics lets the

artist accentuate the scene’s essentials, even if his place of

observation is ambiguous. It’s a naive point of view, the

naturalness of which is proven by how commonly it’s found in

drawings by children.

In her most ambitious pictures, Dorfman takes

this power of synthesis to an extreme by transparently layering

scenes viewed from completely different directions or up close and at

a distance. In a single two-dimensional image, Dorfman presents the

visual information we’d glean by exploring a three-dimensional

landscape over many hours or days. Looking at one of her pictures, we

feel as if we’ve actually experienced

the place.

And in a sense, we have. Dorfman’s photographs

give us access to her experiences and her ambivalence toward a place

that’s at once beautiful and ruined. Through her photographs, we

feel her ambivalence. We don’t only observe

the multiple incompatible certainties that Zeki describes—we

internalize them.

Critic

and artist Jonathon

Keats

is most recently the author of Forged:

Why Fakes Are the Great Art of Our Age

(Oxford University Press).