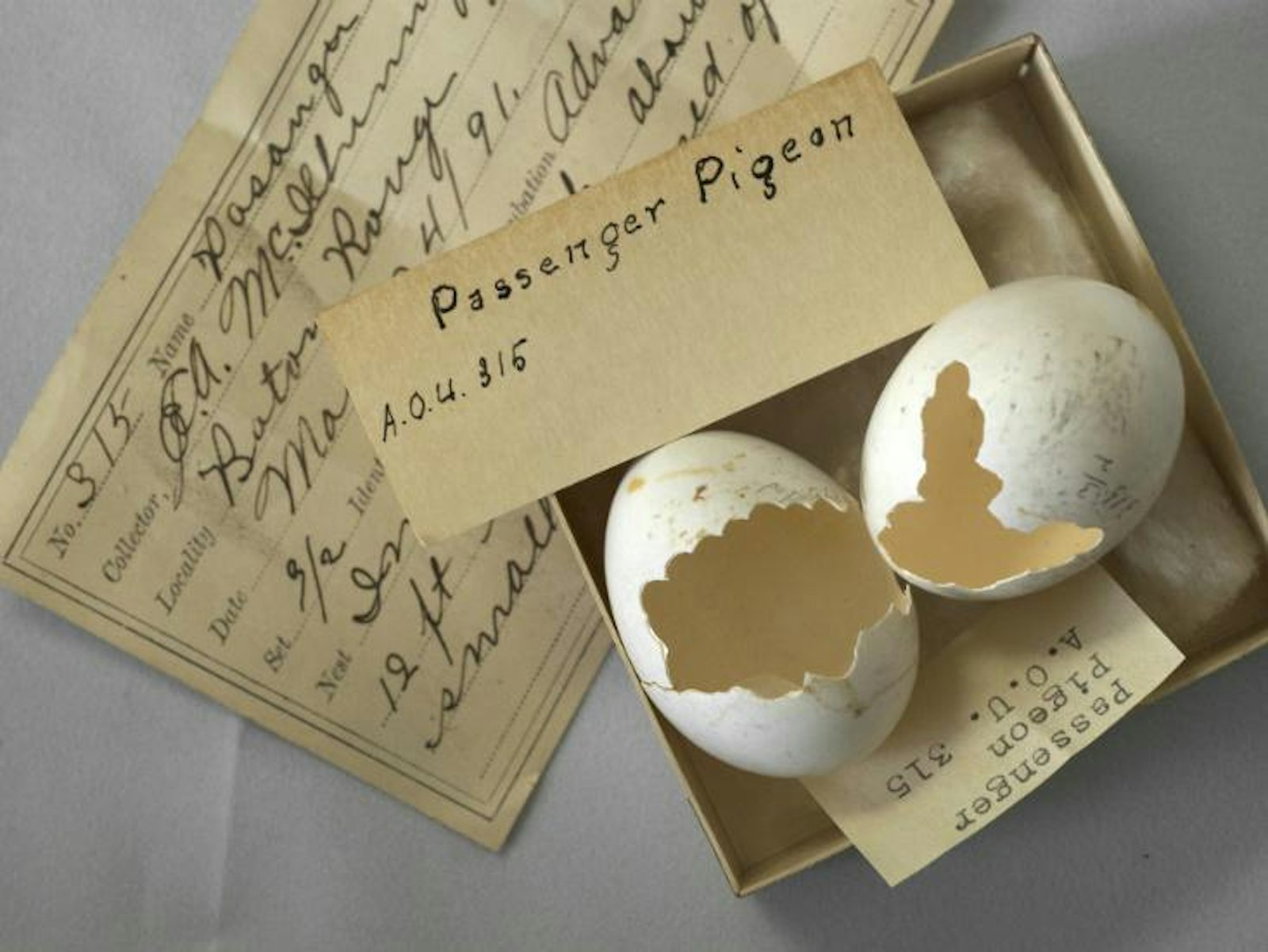

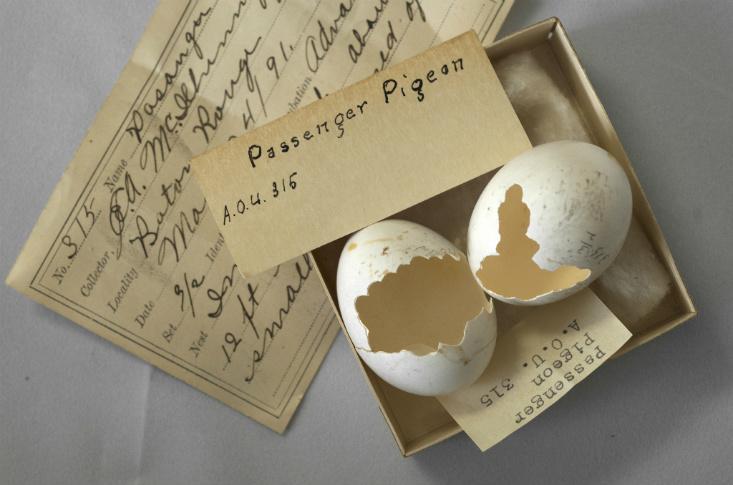

The last passenger pigeon died just over a century ago, though they’ve lived on as symbols—of extinction’s awful finality, and also of a human carelessness so immense that it could exterminate without really trying what was the most populous bird in North America. Centennials being a form of ritual, much has been written about them recently: about flocks a mile wide turning mid-day skies black and taking days to pass, descending upon Eastern forests in a storm of life.

Their sheer, vanished ubiquity is evident in the list of places named after passenger pigeons, which can be found just about everywhere east of the Mississippi and below the Arctic. In New York, where I live, there’s a Pigeon Mountain, Pigeon Creek, Pigeon Lake, two Pigeon Brooks and no fewer than four Pigeon Hills. There’s also a Pigeon Valley Cemetery and a Pigeon Valley Road, though the valley itself now goes by another name.

Yet to some people, the passenger pigeon’s story doesn’t need to have an unhappy ending; they might fly yet again, resurrected by biotechnology. They might become de-extinct.

The notion was unveiled last spring at a day-long TEDx event held in Washington, D.C. at the headquarters of the National Geographic Society, which dedicated an issue of its flagship magazine to the topic. On the issue’s cover a parade of vanished animals poured forth from a test tube: a woolly mammoth and a saber-toothed cat, a giant sloth and a Tasmanian tiger, a giant moa and, of course, a pair of passenger pigeons.

“Do you want extinct species back?” said Stewart Brand, environmentalist and founder of Revive & Restore, a group of researchers and enthusiasts who organized the TEDx panel and coordinate de-extinction research. “Humans have made a huge hole in nature in the last 10,000 years. We have the ability now, and maybe the moral obligation, to repair some of the damage.”

Those themes played out throughout the day, and throughout the de-extinction discourse: bringing back. Righting wrongs. Recreating. Resurrecting. And while a host of technical hurdles, described in depth by Carl Zimmer and Brian Switek in National Geographic and on the website, would first need to be overcome, it’s at least possible to imagine de-extinction happening. We then run into a fundamental question: What do we actually mean by bringing a species back?

“Humans have made a huge hole in nature in the last 10,000 years. We have the ability now, and maybe the moral obligation, to repair some of the damage.”

For one thing, the idea of species can overshadow the lives and experiences of individual animals. At one point during Brand’s talk, he announced to applause the first de-extinction success: a cloned Pyrenaean ibex. Born with grossly deformed lungs, the baby goat lived for just ten minutes. The applause quickly subsided, and while the talk moved on to happier possibilities, I couldn’t shake the thought of that poor goat, called into being only to suffer for the ideal of a species.

Assuming, though, that the reproductive technicalities are worked painlessly out, or that the pain is an acceptable cost: What, really, is a species? It’s theoretically possible that a population of de-extinct animal could contain the entirety of its ancestral genome: a literal, physical embodiment of the lost species, appearing before our eyes as if pulled from history.

Yet those animals would arguably not be truly de-extinct. Whatever knowledge and habits once passed from bird to bird, flock to flock, anything not narrowly contained in genetic programming, would be lost in translation. Eventually, the engineered birds’ descendants would acquire their own habits and knowledge. But they should be regarded that way: not de-extinct travelers from pre-industrial times, but creatures re-interpreted for the 21st century. And for that to happen would require, beyond all the challenges of DNA reconstruction and genome assembly, a feat of cultural engineering.

Critics of passenger pigeon de-extinction have rightly noted that the birds were not merely over-hunted to oblivion. They lost their habitat, too: Vast forests of oak and chestnut and beech were cut down and replaced by farms and cities. Some of those forests have returned, but a new generation of passenger pigeons would inevitably forage in farms and gardens. Would we be willing to share with them?

To re-interpret creatures for the 21st century would require, beyond all the challenges of DNA reconstruction and genome assembly, a feat of cultural engineering.

What of other de-extinction candidates? Would we protect estuaries from development for the eskimo curlew’s sake, when we don’t now protect them for endangered red knots? Ask timber companies to quit logging bottomland hardwood forests out of consideration for ivory-billed woodpeckers? Stop overfishing in the North Pacific so that Steller’s sea cows have enough to eat?

It’s difficult to imagine. All over the world, animals are dying out—either because they’re worth more dead than alive, at least to some people, or because we don’t want to share landscapes and natural resources with them. Wild-animal populations have fallen by 50 percent in the last 1970s; not only are species going extinct, but there’s simply less of what remains.

Last month a northern white rhinoceros died at the San Diego Zoo. There are now just five left. They do not appear to breed in captivity, and the possibility of using de-extinction techniques to save them has been discussed. In principle, I think it’s worth trying—and, for the record, I also like the thought of engineering 21st-century versions of ivory-billed woodpeckers and eskimo curlews. It wouldn’t be resurrection, or bringing them back, or righting a wrong, but it would be better than not doing it.

Now, however, it’s the ghost of the northern white rhino, not the passenger pigeon, that haunts us. If we couldn’t be bothered to save those rhinos from extinction the first time around, will we make room for them in the future? I hope so. But if we do, it won’t be because of our technological prowess. It’ll be because we had a change of heart.

Brandon Keim (@9brandon) is a freelance journalist specializing in science, environment, and culture.