Sometime in the 1860s, five recent Oxford graduates took a trip to Egypt. Together they sailed down the Nile, a tourist attraction even then. To remember their trip, they bought a souvenir in the mummy pits of Deir el-Bahri—the coffin lid of a priestess of Amen-Ra. The high priests of Amen-Ra, named after an Egyptian deity, were military rulers who commanded southern Egypt in the 21st Dynasty (1085 to 945 B.C.), a time of turmoil and strife. Powerful and prone to keep secrets, the priesthood worked to appease the gods that Egypt had clearly angered. With her wide, baleful eyes, open palms, and outstretched fingers, the priestess on the coffin lid seemed to cast a malevolent allure.

On their way back from Egypt, two of the men died. A third went to Cairo and accidentally shot himself in the arm while quail hunting and had to have it amputated. Another member of the group, Arthur Wheeler, managed to make it back to England, only to lose his entire fortune gambling. He moved to America and lost his new fortune to both a flood and a fire. The coffin lid was then placed under the care of Wheeler’s sister, who attempted to have it photographed in 1887. The photographer died, as did the porter. The man asked to translate the hieroglyphs on the lid committed suicide. The coffin lid seemed almost certainly cursed. But this was only the beginning.

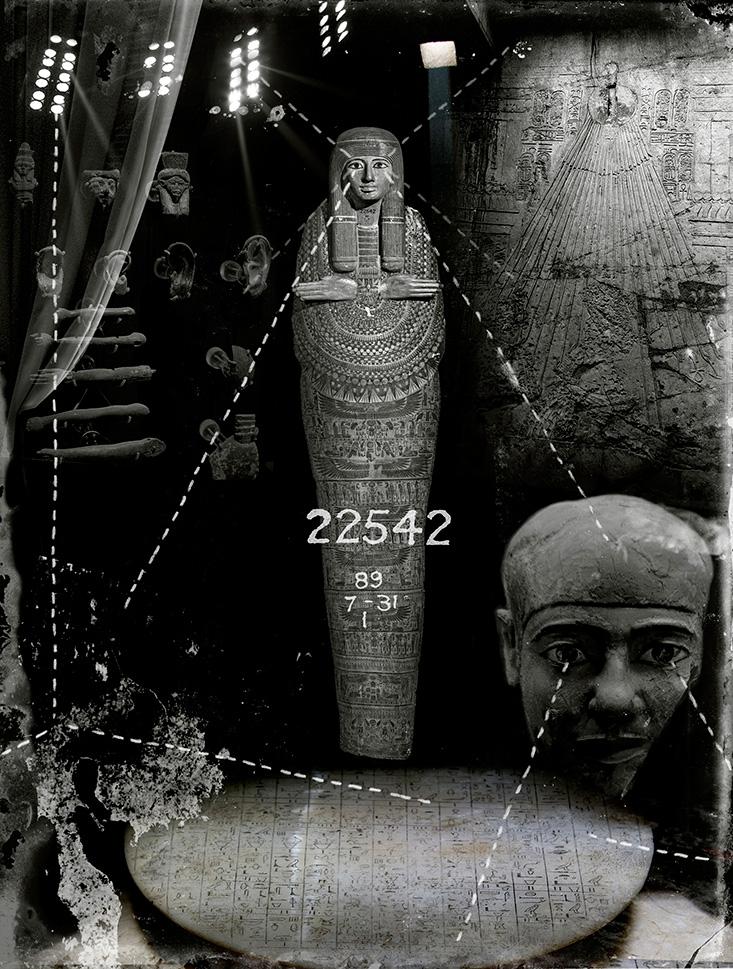

Today, the 5-foot-tall “mummy board” lives in the British Museum, where it’s officially known as “artifact 22542.” The mummified priestess that may have lain beneath it has been lost to eternity. But it has another, more commonly used name: “Unlucky Mummy.” Since its arrival at the museum in 1889, the Unlucky Mummy has been blamed for everything from the sinking of the Titanic to the escalation of World War I. How this piece of wood become so intimately and persistently connected with death and destruction is a story of the endlessly swirling tales that people tell when they are afraid—of change, of politics, of science. It is the kind of story that never dies, only feeds upon itself, updating and morphing and tightening its grip no matter how much light is thrown on it.

By the time the Unlucky Mummy arrived at the British Museum, its reputation had seeped through British private society. While the museum curators generally scoffed at the alleged curse, men at soirees, dinner parties, and “ghost clubs,” traded stories of its powers. But it wasn’t until 1904 that the broader public got a whiff of the curse. That was the year that a young, dashing, and ambitious journalist named Bertram Fletcher Robinson published a front-page article in the Daily Express, called “A Priestess of Death,” about the allegedly haunted mummy. “It is certain that the Egyptians had powers which we in the 20th century may laugh at, yet can never understand,” he wrote.

Three years later, Robinson died suddenly of a fever, and his friends immediately thought of the mummy’s curse. “The very last time I saw him he told me a wonderful tale about a mummy which had caused the death of everybody who had to do with it,” wrote Archibald Marshall, an English author and journalist.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, recalled that he had cautioned Robinson not to get involved with the mummy. “I warned Mr. Robinson against concerning himself with the mummy at the British Museum,” he wrote. “He persisted, and his death occurred… I told him he was tempting fate by pursuing his inquiries, but he was fascinated and would not desist.” Doyle even went so far as to point out that should the mummy kill someone, fever would be the way she did it. “The immediate cause of death was typhoid fever,” he wrote, “but that is the way in which the ‘elementals’ guarding the mummy might act.”

When scientists went into tombs to gather relics, they weren’t just moving rocks, they were moving sacred ways of thinking.

Robinson was not the only alleged victim. The list of stories about the mummy’s influence began to grow longer—people who sketched the mummy having mysterious accidents, a lady falling down the stairs, a captain meeting financial ruin, a psychic claiming the mummy haunted him for weeks. There was a rumor that the mummy had been on the Titanic and caused the ship’s deadly collision. One person claimed the mummy, at the peak of her wrath, had been presented to the Kaiser and caused the outbreak of World War I.

As it happens, the Unlucky Mummy arrived in England during the perfect curse-making storm. It was a time when science challenged traditional beliefs, experiments into the occult were becoming more common, and when tales of ghosts and threatening monsters were entering their golden age. The Victorians were afraid of a lot of things: empires, justice, the rise of women in society, knowledge, truth, and the role of expertise. And on top of that, there was a war going on.

At the time, Britain was occupying Egypt. It had invaded the Middle Eastern country in 1882, bombarding Alexandria for 10 and a half hours from the sea in an attack that was largely one sided—the British didn’t lose a single boat. The fires that followed destroyed much of the city and two days later the British army entered Alexandria and took on Egyptian forces in a handful of skirmishes, the most notable being the battle at Tel-el-Kebir. Because the Egyptian land was flat and open, the British decided to attack at night. After an hour of fighting, the Egyptians fled. The British military stayed in Egypt in a variety of capacities until 1922.

While the occupation of Egypt was a military success, it was met with trepidation back home. Should a European power intervene in the goings on of a Middle Eastern country? The British said they were there to help depose a tyrannical rule, but the British people weren’t sure that was their government’s job in the first place. But while the occupation troubled many, some didn’t want to outwardly express their anxieties. So they turned to objects that represented the country in question: Egyptian artifacts.

“You can’t talk about how difficult it is to occupy another country because that’s unpatriotic,” says Roger Luckhurst, a professor of literature at Birbeck College, University of London, who details the Unlucky Mummy’s journey through myth and reality in his 2012 book, The Mummy’s Curse. “This is a narrative that lets you talk about it in another way.” The idea that objects from Egypt like the mummy board would exact revenge was a way to express anxiety without actually talking about war.

As wartime fears ran through much of England, science began to take people further down rabbit holes of knowledge, causing them to worry about just how far scientists would go to uncover truth. When scientists went into tombs to gather relics, they weren’t just moving rocks, they were moving sacred ways of thinking. “There are incentives to disturbing the dead, and archaeology is one of them,” says Kathlyn M. Cooney, an Egyptologist at the University of California in Los Angeles. The archaeological incentive, however, was also uncovering guilt.

In the 1899 novel, Pharos the Egyptian, by Guy Boothby, Pharos asks the son of a famous Egyptologist, “And pray by what right did your father rifle the dead man’s tomb?” Perhaps, he continues, “you will show me his justification for carrying away the body from the country in which it had been laid to rest, and conveying it to England to be stared at in the light of a curiosity.” He could just as easily have been talking about the priestess of Amen-Ra. “Here you’ve got a mummy board that’s depicting a human female, and that mummy board was meant to be kept in an intact tomb,” Cooney says. “And it’s not. It’s floating around the world, bought and sold, and now it’s on display. It’s separated from its mummy, it’s been wrested from everything it’s been a part of. That upsets people. It worries people.”

It wasn’t just in the realm of stories that the British were venting their fears. This was also the era that gave birth to tabloid journalism. Newspapers fanned the flames of anxiety and reinforced them, building a base for more tales of monsters and mummies. In the late 1890s the Daily Mail took flight. It was joined by the Daily Express, which published the original Unlucky Mummy story, “A Priestess of Death,” The Morning Star, the Daily Sketch, and others, dedicated to selling papers with bold headlines and little regard for facts. Philosopher R.G. Collingswood wrote that tabloids were places where the reader was expected to “think of the news not as the situation in which he was to act, but as a mere spectacle for idle moments.” The Unlucky Mummy was too big of a spectacle to remain fodder for just England’s tabloids. A 1909 headline in William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner exclaimed, “Ghost of Mummy Haunts the British Museum: MUST GO NOW: For Thirty Years Dead Egyptian Priestess has Spelled Disaster.”

The Unlucky Mummy story, Luckhurst suggests, forged a template for an even more spectacular story about excavating ancient spirits. In 1922, the long sought-after tomb of King Tutankhamen was uncovered, and both rigorous and tabloid papers were jostling to get their hands on the goriest and most gilded stories that emerged from the burial ground. Lord Carnarvon, the man who funded the expedition that found King Tut’s tomb, had signed a strict and exclusive agreement with the Times of London that essentially locked all other papers out of the story. The competition got their revenge by stoking rumors that Carnarvon, who died from blood poisoning (he was bitten by a mosquito) not long after the excavation, was driven to his grave by vengeful Egyptian spirits. The Daily Express gave voice to a Christian mystic novelist who claimed, based on a rare book called The Egyptian History of the Pyramids, that “the most dire punishment follows any rash intruder into a sealed tomb.”

Today the British Museum has little to say about the Unlucky Mummy. The artifact page for the mummy board has a brief note, hidden in the curator’s comments. It recounts a few of the most notable myths, including that the mummy was on board the Titanic, and adds: “Needless to say, there is no truth in any of this; the object had never left the Museum until it went to a temporary exhibition in 1990.”

For Luckhurst, the museum’s dismissal of the myths is unfortunate. The myths, he says, “tell us a lot about how people react and respond and interact with these ancient artifacts.” Once an item is encased in glass, given a number and archived into a database, it is supposed to be stripped of its mythical aura and magic. Pushing magic away, though, only makes people cling to it harder, especially when the object is intimately connected with human remains. “We’re always going to feel ambiguous and vaguely transgressive about these sorts of things,” Luckhurst says.

Indeed, mummy stories still walk among us. In 2013, a headline in England’s Manchester Evening News read: “The curse of the spinning statue at Manchester Museum.” The story concerned a 10-inch-tall statue of a man, found in an Egyptian mummy tomb, that mysteriously spun in its display case. An Egyptologist quoted in the paper, explained, “In Ancient Egypt they believed that if the mummy is destroyed then the statuette can act as an alternative vessel for the spirit. Maybe that is what is causing the movement.” In fact, the base was slightly uneven, and tiny vibrations from road traffic and visitors’ footsteps were making the statue rotate.

In a culture of anxiety, conflicted over how science shapes our understanding of the world, the allure of the occult remains. Will Gervais, a psychologist at the University of Kentucky who studies superstitious beliefs, says the British Museum should embrace the Unlucky Mummy’s curse. “I’d advise the museum to sell T-shirts about the mummy, then take the proceeds and pour them into other science-education programs that are more likely to succeed.” And, in one way, the British Museum has. Last summer it showed the 1959 film The Mummy in its courtyard. “You can bury people’s superstitions under a mountain of evidence,” Gervais says, “and the superstitions will climb right on out.” Not unlike an unlucky mummy.