Latest

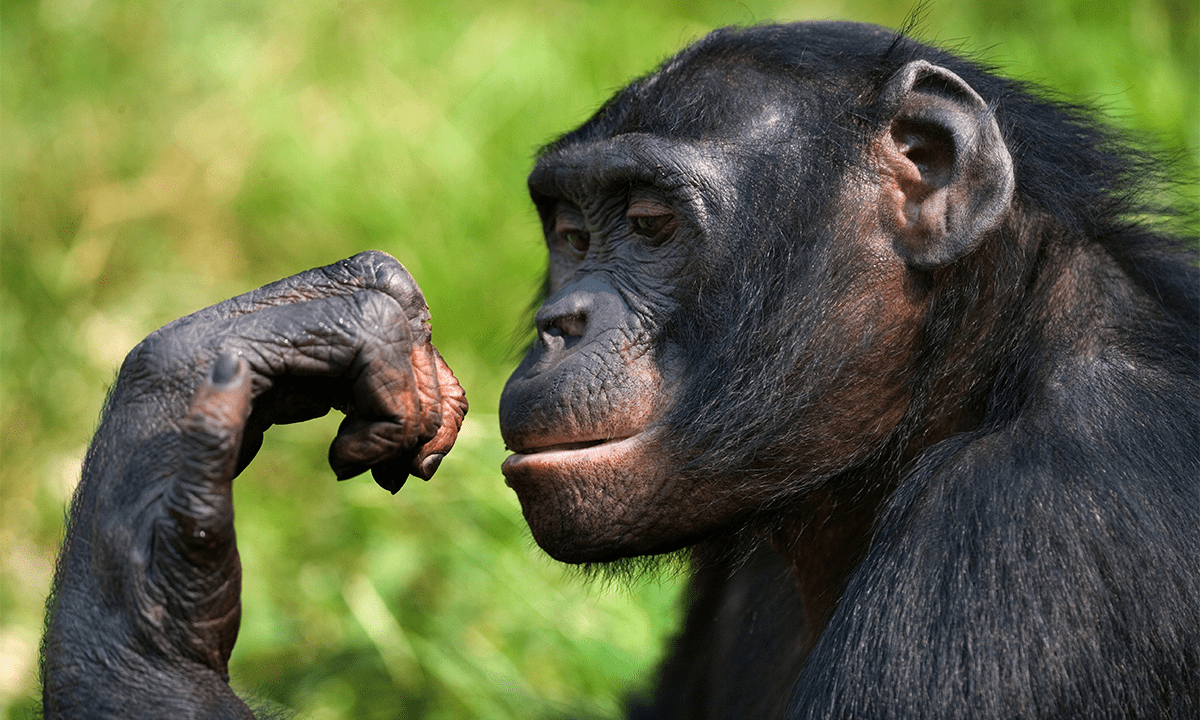

Humans Can Read the Expressions and Feelings of Our Primate Cousins

Just like our primate cousins can read human expressions

Latest Stories

The Science Behind the Perfect 3-Point Shot

The difference between a satisfying swish and an embarrassing air ball

How Flowers Transformed Planet Earth

An interview with biologist David George Haskell about his new book

Psychology

See more PsychologyYou Can Still Improve as You Age—With the Right Mindset

New research is challenging traditional assumptions of aging

Weed Not Only Sends Memories Up in Smoke, It Reshapes Them

Break out the sticky notes next time you smoke

Are You Smart Enough to Avoid Falling for “Corporate Bullsh*t”?

New research points to a troubling relationship between buzzwords and decision-making

Environment

See more EnvironmentIt’s Not Just You. Subways the World Over Are Feeling Hotter

Complaints of extreme heat are rising

The Ancient Cold Snaps That May Have Shaped Human Evolution

Here’s when Earth’s climate became chaotic

Is a Strictly Enforced Fishing Ban Saving the Yangtze?

Ecologists detect promising, early signs of river recovery

Get unlimited, ad-free Nautilus. Become a member today.

History

See more HistoryHow Three Students Designed an Atomic Bomb

A top-secret 1960s project tasked physics postdocs with building The Bomb

The Thrill of Science in 2042

A science historian explains how science got its groove back. A fictional dispatch from the future.

How Energy Politics Played Out on the White House Roof

The quick removal of Jimmy Carter’s futuristic solar panels echoes more recent feuds over renewables

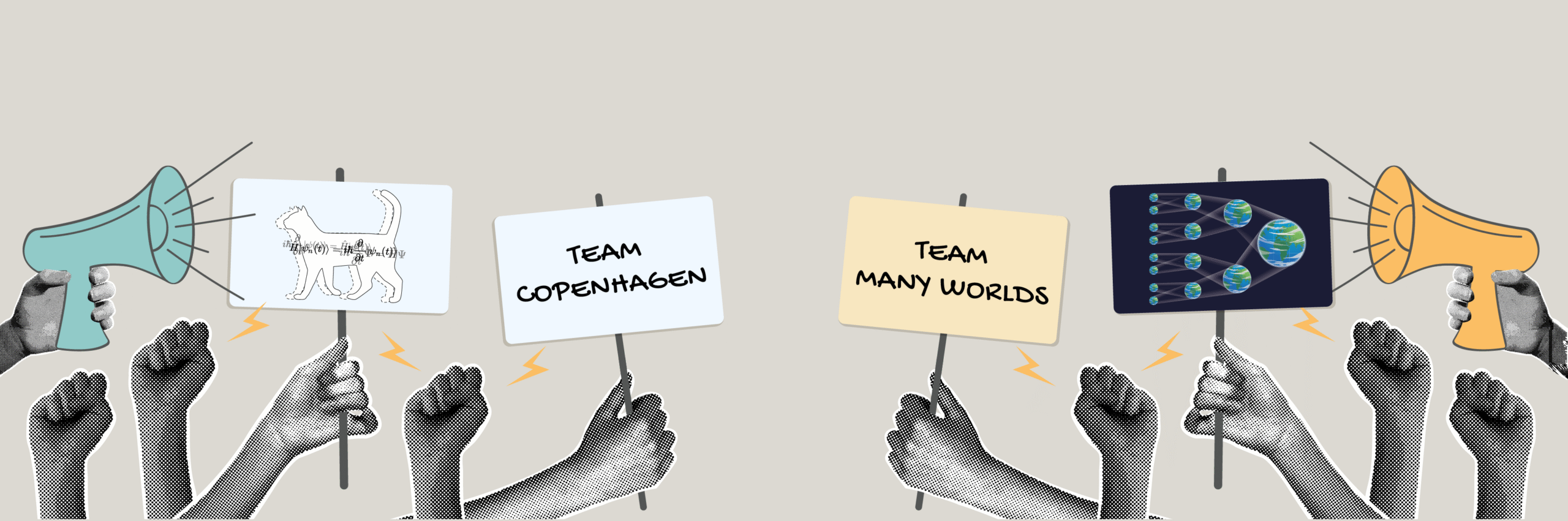

Physics

See more PhysicsPhysicists Uncover How Long It Takes to Get the Last Drop of Syrup

How to tackle a common kitchen problem with fluid dynamics

Communication

See more CommunicationWhat Would Richard Feynman Make of AI Today?

The scientific sage was always suspicious of grand promises delivered before details were understood

Get the Nautilus newsletter

Cutting-edge science, unraveled by the brightest living thinkers.

Sociology

See more SociologyThe Vibes Have Been Off in the US for Decades

New survey analysis reveals a sense of national deterioration

Does Belief in God, not Political Party, Drive Conservatism?

Religious “nones” may be less socially liberal than they used to be

Parachute Science Continues to Prevail in Global South Biodiversity Studies

The privilege of describing new species is skewed to Global Northerners

Why Does the United States Have So Many Tornadoes?

No other country comes close

Read more

See all postsAncient People Traded Live Parrots Across South America for Thousands of Years

Polly has been wanting a cracker for millenia

Inside the Brains of Monks Who Have Meditated for 15,000 Hours

They may offer new clues to the mystery of consciousness

Were You Born to Love Music?

How you respond to art—from poetry, to visual art, to music—may be partly written in your DNA

Baby Boomers Are a Transition Generation in Our Longevity Crisis

Lifespan in the United States plateaued over a decade ago

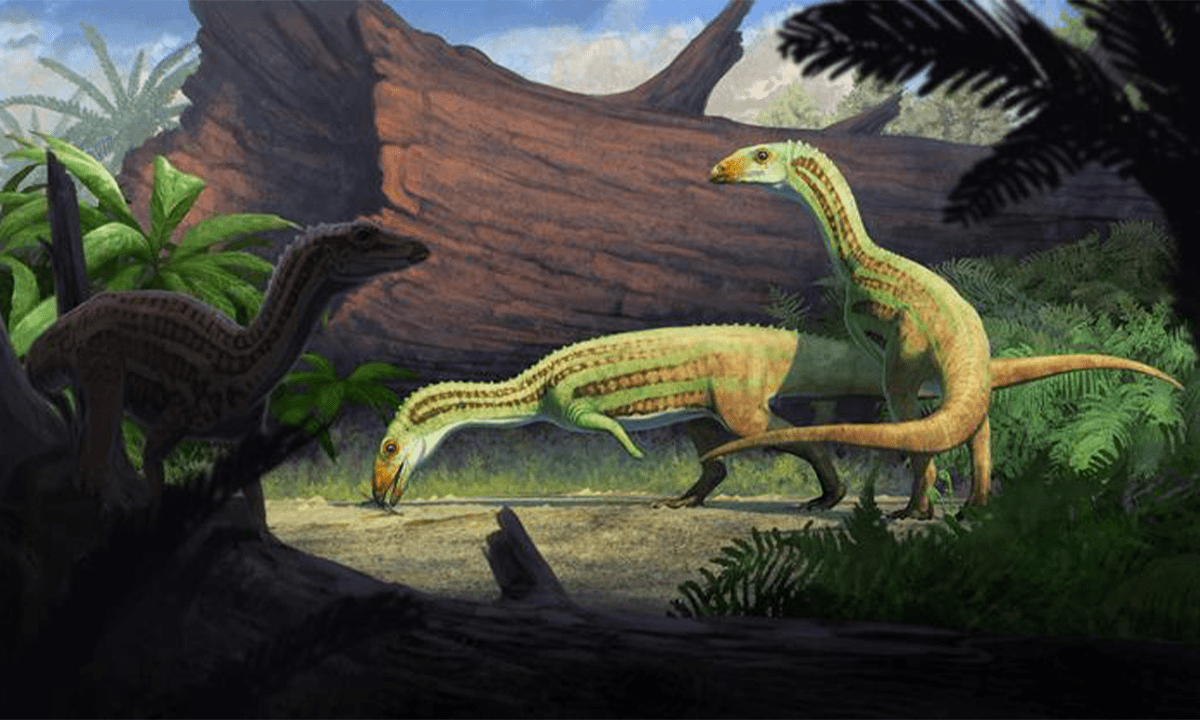

This Ancient Crocodile Ancestor Learned to Walk on Two Legs

It was a childhood crawler before it walked upright

Some Memories Live in the Brain Even If We Can’t Recall Them

It’s all coming back to me now

Restoring Panama to When Prehistoric Beasts Roamed the Jungle

The Central American nation never fully recovered from the loss of its megafauna